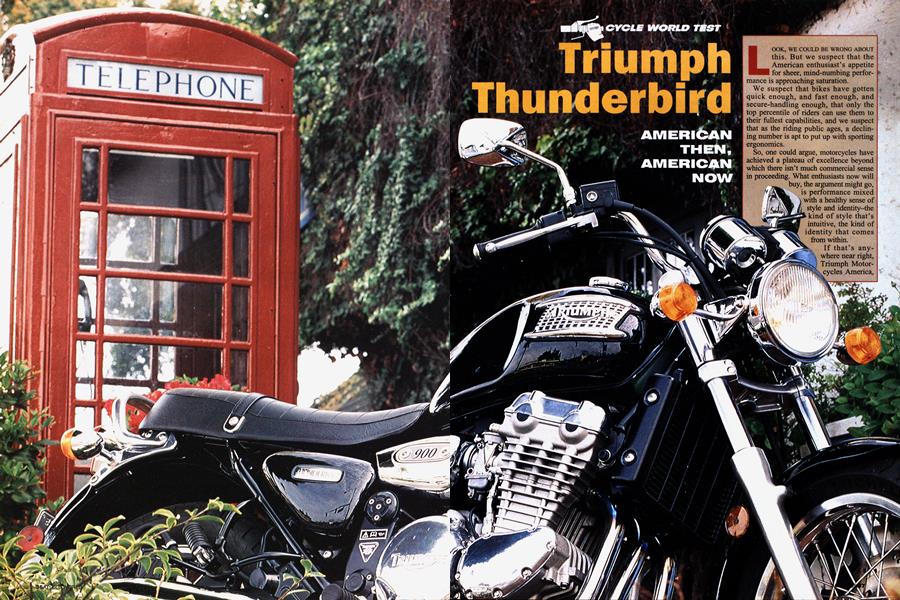

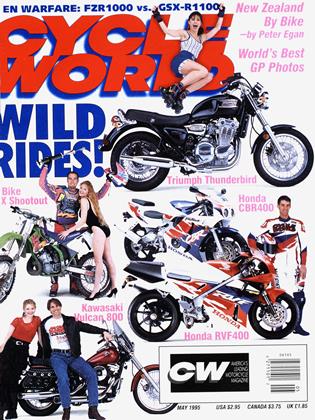

Triumph Thunderbird

CYCLE WORLD TEST

AMERICAN THEN, AMERICAN NOW

L00K, WE COULD BE WRONG ABOUT this. But we suspect that the American enthusiast's appetite for sheer, mind-numbing performance is approaching saturation.

We suspect that bikes have gotten quick enough, and fast enough, and secure-handling enough, that only the top percentile of riders can use them to their fullest capabilities, and we suspect that as the riding public ages, a declining number is apt to put up with sporting ergonomics.

So, one could argue, motorcycles have achieved a plateau of excellence beyond which there isn't much commercial sense in proceeding. What enthusiasts now will buy, the argument might go, is performance mixed with a healthy sense of style and identity-the kind of style that's intuitive, the kind of identity that comes from within.

If that's any where near right, Triumph Motor yc1es America, Ltd., is in for some good times, thanks to the Thunderbird 900, the company’s nod to a past it otherwise has tried to put behind it. How far behind? So far behind that company spokesmen make no bones about saying, “Look, we’re a new company;” so far behind that Triumph’s logo is subtly different from the original; so far behind that for its first five years of production, its bikes bore no resemblance at all to Triumphs built in Meridan, the marque’s former home.

But that was then and this is now'; that was Europe, where expectations are one thing; and this is America, where they’re quite another. In Europe, if it ain’t hot, it’s not. Happenin’, that is. But in America, Triumph is a river of motorcycle consciousness that runs very deeply through motorcycling gentlemen of a certain age. Triumph’s marketeers recognized this-they’d have to be blind not to-and got up a special Triumph just for the American market, a Triumph that trades hot performance for hot styling.

Ah, but w'hich Triumph? The answer was surprisingly easy. It had to be a Thunderbird, because the first model designed specifically for the American market, all the way back in 1949 for sale in 1950, was the 6T Thunderbird. The name is the subject of more lore: Either Triumph majordomo Edward Turner suggested it, or it came from the mythology of native Americans, or it was the name of a scruffy Southeastern roadhouse where Triumph officials lodged while on a business trip. In spite of that, the Thunderbird so far is sounding like a triumph of style over substance. That triumph continues with the wheels-Spanish aluminum Akronts laced with stainless-steel spokes, but shod with modern Michelin A59/M59 tubeless radiais. The anomaly here is that the Thunderbird's spoke-wheels don’t permit the tires to be used in tubeless form. They therefore contain tubes, and this is where things get strange. You see, the Thunderbird is not equipped with a centerstand. Get a flat out on the road away from home, you’re stuck. No way to plug it, as you might do to a tubeless tire as an emergency measure, no easy or graceful way to pull the wheel off so that you can patch the tube. Style, two; substance, zip.

Wherever its name came from, the Thunderbird is back, and its resemblance to the original artifact is but fleeting and skin deep.

This is not your father’s Triumph. It is, instead, a thoroughly modern machine built the same way, using the same design, tooling and core pieces as the other bikes in Triumph’s line. The Thunderbird, however, has some significant differences: Its frame and engine cases, its cylinders, seat, tank, bodywork-none are shared by another Triumph.

Start w ith the frame. It begins the production process as the basic steel backbone unit used by the rest of the Triumphs, but welded to it is a different rear subframe than is used elsewhere. This is used in conjunction with a 16-inch rear w'heel to give the bike its lower, custom-style line. The swingarm is as on other Triumphs, right down to the eccentric axle adjusters and single shock, w'hich is adjustable only for preload. Triumph’s masters looked at equipping the T-Bird with dual shocks, but decided to leave well enough alone.

Having modified the line of the frame, Triumph’s stylists, aided by GP designer John Mockett, Triumph owner John Bloor and Marketing Manager Mike Lock, covered it with design elements strongly evocative of Triumphs of yore, the purpose being to reach deep inside the American enthusiast to chime a chord of recognition. These evocations include a fuel tank that not only mimics classic Triumph shapes, but also wears a garden-gate-style tank badge; a classic flat, broad, stepless seat with the name Triumph heat-embossed in its rear panel; and chromed silencers that don’t exactly match the pea-shooter-shape of those found on classic Triumphs, but which aren’t too far afield, either.

None of this was arrived at easily. Triumph’s decision makers purchased a variety of classic Triumphs and rode them to see how they felt. They then tried to transfer that feel, position and perspective to this new Thunderbird. They succeeded pretty well. Sitting on the bike, it feels smaller than, and different from, its siblings. The sense is that you sit down in it more than perch upon it. Look down, and the shape you see between your knees could only belong to a Triumph fuel tank.

are much less evocative, in spite of the best efforts of Triumph's stylists. The engine residing there is basically the same 885cc, dohc, 12-valve Triple found tucked under other Triumph fuel tanks, containing the same crankshaft, pistons and valves, but with many important differences. These differences begin with softer cams than used in other Triumph Triples, the purpose being to trade top-end rush for lowand midrange torque and mellowness. Engine cases, cast by Cosworth Engineering to a very high level of finish, use different internal webbing than Triumph's more powerful Triples. The head and cylinder also are dif ferent-these, which complete a thoroughly liquid-cooled engine, wear a set of coarse-pitch fins that attempts to mimic traditional air-cooled designs. Engine sidecovers also were restyled for use on the T-Bird. Covered in thick chrome, they demonstrate a resounding commitment to quality that is echoed everywhere in this bike, from the meaty feel of its clutch to the machine-tool precision of its shifting mechanism to the solid beauty of its cast shifter and brake lever. Somebody put a lot of thought into this bike's bits and pieces.

Not that it matters. Park the bike anywhere, and here’s what happens every time: men, aged 40-something, approach, slack-jawed and glassy-eyed with reminiscence and desire. They stroke the bike’s tank, caressing its paint as they might a lover’s silken leg. They ask where they can get theirs. You wish they'd move away before they get the bike sticky.

Do you begin to think Triumph’s on to something here?

If your mind’s still not made up, all it will take will be a ride. You’ll love it or hate it, depending upon your expectations and depending upon whether you judge a bike by how it looks or by how it works.

Climb aboard and settle onto the broad, comfortable seat. Grasp the mid-rise handlebar, settle your feet on the ground-easy, since the seat-height is 1.5 inches less than that of the Daytona 900, one of the T-Bird’s close cousins. Nestle down in the saddle, get comfortable, rock side-toside. Damn, it feels a lot like an old Trumpet.

That familiarity fades quickly, however, when you examine the smooth, modem switchgear, the instruments and the bank of circular warning lights-these arc so dim as to be next to useless, but at least they’re cleanly styled.

Familiarity fades even more when you click on the ignition key and punch the starter-oh, you thou-

ght maybe the yester-thinkers behind this bike equipped it with a kick-starter? The bike’s 885cc Triple hums smoothly into life, exhibiting not much vibration. The engine is solidmounted but counterbalanced, so it has the good manners not to intrude upon your riding pleasure and comfort.

It does provide riding pleasure, pulling strongly from right off idle to its 8500-rpm redline, but without the sort of mid range power bump that makes other motors in the line so much fun to use. Also missing is the classic Triumph exhaust note. What you hear with this bike is, well, not much. The silencers do maybe too good a job of muting the healthy rasp of the bike's even-firing three cylinders. Power in the upper registers tapers off to the point where the engine will not pull to its rev limit in top gear, maxing out at 11 5 miles per hour.

Going through the gears, however, is a joy, for Triumph offers one of the finest clutch and gearbox combinations anywhere, with great feel and sensitivity to the clutch and wonderful precision to the shifting action.

Suspension action is pretty good, with spring and damping values on the components close to optimal for one-up riding, as long as the preload on the shock is wound up to max.

Out on the road, what becomes immediately evident is that the Thunderbird is dedicated to smooth, relaxed riding-local riding, even, since its fuel capacity is 4 gal lons. We found ourselves on Reserve at 90 miles. Steering is slowish but fairly neutral, with a fine lightness of feel that is aided by the wide handlebar and by the characteristic light touch of the Michelin A89 front tire. The bike's single front disc feels powerful enough to provide brisk stops without ripping the spokes out of the rim, but is a bit numb in feeL fortunately, the bike's wheelbase is long enough to invite use of the rear disc without also inviting the perils of rear braking.

You can ride the Thunderbird hard and its only protest will be a bit of chassis wiggle during really vigorous cornering. But hard riding isn’t what it’s for; other bikes in the Triumph line are dedicated to that benighted pastime. The Thunderbird 900 is a kind of standard-cruiser. Its up-straight riding position is pretty uncomfortable for high-speed riding; you have to hang on tight to avoid being blown off the back of the bike. But its position is just right for low-pressure sightseeing.

The Thunderbird works well for what it is. It represents the outlook of Triumph’s corporate rearview mirror, a nod to heritage and to a perceived, and apparently real, American appetite for nostalgia. It’s a stunningly good vintage bike, if that’s really what you want. If you want a more modern motorcycle, well, Triumph builds those, too. Still, the Thunderbird is so far superior to any old Triumph that there’s really no comparison. It has the look, sort of; and the feel, sort of. Our testbike even drooled a bit of oil, probably from its primary-shaft seal, onto our garage floor, the first of any of the new-generation Triumphs we’ve seen leak anything.

What’s really amazing is how different the Thunderbird, with its shared family components, is from the other bikes in the Triumph line. That’s just what the company, fully aware of the name’s clout in the U.S., is counting on. Our guess is Triumph will sell a lot of these. Our further guess is most Thunderbird buyers will be outstandingly happy with their new motorcycles. □

TRIUMPH THUNDERBIRD.

SPECIFICATIONS

$9995

EDITORS' NOTES

MY PARENTS HADN’T EVEN MET WHEN the original Thunderbird was introduced. And when I was growing up in the mid-60’s, my father, uncle and friends’ dads didn’t have motorcycles. For me, then, there are absolutely no feelings of nostalgia towards this new Triumph.

Early-30s types, such as myself, may not be in the Thunderbird's target audience, but I would be delighted to own one of these attractive, beautifully crafted motorcycles. Why? It’s comfortable, fun and different.

The engine makes less horsepower than Triumph’s other Triples, but there’s still plenty of steam in this cup of tea. And as Triumph promised when rumors of this bike leaked out, handling is quite competent.

You can’t say, “competent for this type of bike,” because the T-Bird is unlike anything else. In this age of graffiticovered sportbikes and cookie-cutter cruisers, this neo-classic stands alone. In my mind, that makes it worthy of considerable merit.

-Robert Hough, News Editor

I HAVE SEEN THE CUSTOMER FOR THE Thunderbird 900, and he is me. Or at least like me; he’s guys my age, with motorcycling backgrounds as complex as their resumes, with faces as wrinkled as original Triumph seat covers. I have learned the hard way, however, that there is very little profit in looking back, the way the Thunderbird seems to. I likewise have learned the joy of the new and unexpected, whether it’s tomorrow’s new job assignment or the joyful frustration of dealing with new computer software. It wasn’t easy. But ultimately I accepted the benefits of new-think. Maybe that’s why I’ve traded off my LPs in favor of compact discs, why I carry a laptop computer and no longer own a typewriter, why there’s a modern, big-bore sportbike lurking where my BSA Lightning and Suzuki 1100G used to live.

The Thunderbird is fun to look at, I’ll give it that. 1 understand why Triumph needs it. 1 guess I also understand why, as competent as it is, I don’t.

-Jon F. Thompson, Senior Editor

HERE’S A QUESTION. WILL TRIUMPH’S retro-bike succeed where others-I’m thinking of the Honda GB500, the Kawasaki Zephyr series-have failed?

I think, yes, because like HarleyDavidson, king of the yesterbikemakers, Triumph has a lot of retro to draw from.

Doesn't mean I’m a big fan of the concept or of the T-Bird, though. This is a splendid-riding motorcycle, but if I wanted a standardstyle Triumph, I’d stop in front of the Trident 900, which makes 38 more horsepower, has triple disc brakes, and wears cast wheels and tubeless tires. A modem standard, in other words. Plus, at $7995, it’s $2000 less expensive than the Thunderbird, an unsung bargain of Triumph America’s lineup.

If I still lusted after an old Triumph, I’d use the 2K to take a sizable bite out of the purchase price of a restored 1966 Bonneville-you know, the white one with the cool orange stripes on its tank.

-David Edwards, Editor-in-chief

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontLove At First Ride

May 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsGlowing Inspirational Restoration Messages

May 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Mpg Papers

May 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Storming Standard

May 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupTriumph's Getting Tubular, Going Raging

May 1995 By Robert Hough