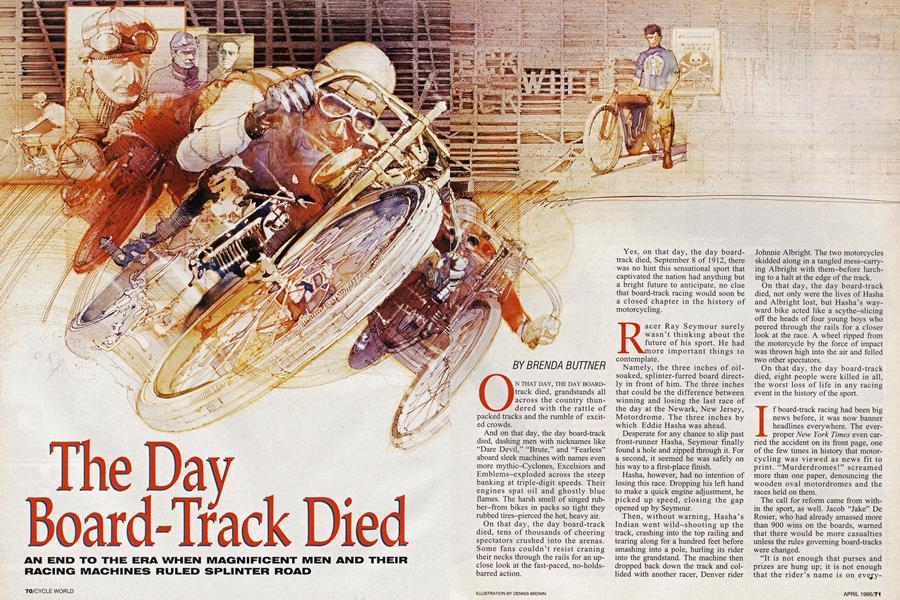

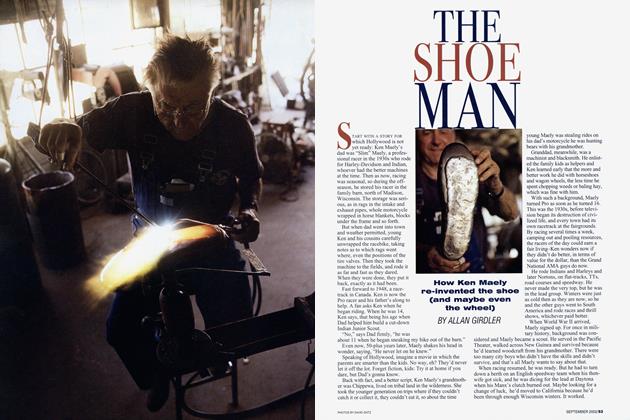

The Day Board-Track Died

AN END TO THE ERA WHEN MAGNIFICENT MEN AND THEIR RACING MACHINES RULED SPLINTER ROAD

BRENDA BUTTNER

ON THAT DAY, THE DAY BOARD-track died, grandstands all across the country thundered with the rattle of packed tracks and the rumble of excited crowds.

And on that day, the day board-track died, dashing men with nicknames like “Dare Devil,” “Brute,” and “Fearless” aboard sleek machines with names even more mythic—Cyclones, Excelsiors and Emblems—exploded across the steep banking at triple-digit speeds. Their engines spat oil and ghostly blue flames. The harsh smell of singed rubber-from bikes in packs so tight they rubbed tires-pierced the hot, heavy air.

On that day, the day board-track died, tens of thousands of cheering spectators crushed into the arenas. Some fans couldn’t resist craning their necks through the rails for an upclose look at the fast-paced, no-holdsbarred action.

Yes, on that day, the day boardtrack died, September 8 of 1912, there was no hint this sensational sport that captivated the nation had anything but a bright future to anticipate, no clue that board-track racing would soon be a closed chapter in the history of motorcycling.

Racer wasn’t Ray thinking Seymour about surely the future of his sport. He had more important things to contemplate.

Namely, the three inches of oilsoaked, splinter-furred board directly in front of him. The three inches that could be the difference between winning and losing the last race of the day at the Newark, New Jersey, Motordrome. The three inches by which Eddie Hasha was ahead.

Desperate for any chance to slip past front-runner Hasha, Seymour finally found a hole and zipped through it. For a second, it seemed he was safely on his way to a first-place finish.

Hasha, however, had no intention of losing this race. Dropping his left hand to make a quick engine adjustment, he picked up speed, closing the gap opened up by Seymour.

Then, without warning, Hasha’s Indian went wild-shooting up the track, crashing into the top railing and tearing along for a hundred feet before smashing into a pole, hurling its rider into the grandstand. The machine then dropped back down the track and collided with another racer, Denver rider

Johnnie Albright. The two motorcycles skidded along in a tangled mess-carrying Albright with them-before lurching to a halt at the edge of the track.

On that day, the day board-track died, not only were the lives of Hasha and Albright lost, but Hasha’s wayward bike acted like a scythe-slicing off the heads of four young boys who peered through the rails for a closer look at the race. A wheel ripped from the motorcycle by the force of impact was thrown high into the air and felled two other spectators.

On that day, the day board-track died, eight people were killed in all, the worst loss of life in any racing event in the history of the sport.

If news board-track before, racing it was had now been banner big headlines everywhere. The everproper New York Times even carried the accident on its front page, one of the few times in history that motorcycling was viewed as news fit to print. “Murderdromes!” screamed more than one paper, denouncing the wooden oval motordromes and the races held on them.

The call for reform came from within the sport, as well. Jacob “Jake” De Rosier, who had already amassed more than 900 wins on the boards, warned that there would be more casualties unless the rules governing board-tracks were changed.

“It is not enough that purses and prizes are hung up; it is not enough that the rider’s name is on evejybody’s lips; it is not enough that one is a world champion,” he argued in a Motorcycling article titled “Stop Killing Off Our Racing Men!” “All of these are not enough recompense for crippled bones, long stays in hospitals and untold sufferings.”

De Rosier knew of what he wrote. Strapped in a hospital bed with his thigh broken in three places, the board-track pioneer was fighting for his life after a grisly crash at the Los Angeles Motordrome in I9l2. When he arrived home in Springfield, Massachusetts, for a third operation in early 1913, a local newspaper report pronounced the crowd favorite “rosy-faced” and predicted “he would be back because he was a veritable lion.”

To succeed on the boards, one had to be lion-hearted. The sport demanded unflinching bravery-the courage (or, as some critics said, stupidity) to throw oneself onto a skinny bike with no brakes and 2-inchwide tires, then burst at speeds surpassing 100 mph into a tight cluster of racers fighting for position on weathered wooden tracks.

Built of edge, of2x4 the or 2x2 motordromes boards laid were steeply banked, usually at about 60 degrees. It didn’t help that they were often poorly maintained. Lumber was expensive, and, with several races run daily, the wooden ovals were usually rundown. Jim Davis, one of the last living board-trackers, recalls riding one track in Fresno, California, that was so dilapidated, riders had to dodge holes large enough to catch a tire. “It was in horrible shape,” he remembers. The local fire department was sent in before every race to hose down the track in the hope that water would swell the boards.

Oil on the boards was another peril racers faced. Engines of the era used rudimentary total-loss lubrication systems, and during races saturated the track with slippery oil.

Management’s solution only made matters worse. Lye was used to cut the oil, but drops of the hazardous liquid sometimes flew straight into the eyes of riders who had removed goggles clouded with oil.

Yet all that danger made for a spectacular show. There was the time on an Oakland, California, track soaked with oil, that HarleyDavidson racer Joe Wolters won a mile race...on his back.

“One hundred feet from the finish, Wolters’ mount slid completely from under him, and he crossed the line a winner, in a slide,” described the local newspaper. “The slide lasted for 450 feet!”

Wolters had gathered a batch of long, wooden splinters in his back and hands, but rushed off to catch a train to his next race and ignored the slivers until a Pullman porter could extract them. Not unlike many racers of the time, Wolters was much more worried about his bike than his body.

o wonder. The machines were magnificent, unlike anything the racing world had ever seen. Robust Harley-Davidsons powered by 61-cubicinch engines battled muscular eightvalve Indians. The fantastically fast Cyclones streaked around the tracks in brilliant yellow flashes, flirting with spirited Excelsiors and their strong intakeover-exhaust engines.

These bikes were all about speed-they shattered 100 mph and pushed beyond.

The motorcycles were not so sophisticated, however, when it came to braking and handling. And on the boards, there was little room for error. Literally. Jim Davis remembers well. “You could reach out and touch each other,” he says.

Which is exactly what many racers did. “It was not always the man on the fastest machine who won the race,” reports one newspaper account from the era. “Hooking, bumping and running a competitor up the track were some of the things that the referee closed his eyes to, while for a man to put his elbow on a competitor’s cutout and stop his motor was not uncommon.”

That was board-tracking: no brakes, few rules, but lots of action.

mericans loved it. Board-tracking became the social event of the weekend in many places. Risk-taking racers such as Wolters and De Rosier drew crowds of spectators dressed in their Sunday best. Nearly every city had a track; many hosted two. At the bigger ones, up to 10,000 fans paid 25 cents general admission and 75 cents for covered seating to watch the most exciting spectacle around.

“It is a most dangerous form of racing, but it had the crowd as there was something doing every second.” pronounced the sports page in one newspaper. “It is nip and tuck as the men fight it out on the boards and the danger is such that a frightful accident may happen any second.” Management didn’t mind cashing in on that risk. “Neck and Neck with Death,” shrieked billboards outside many motordromes.

At the Los Angeles Stadium in 1912-in the crash that put him in the hospital for nearly a year and inflicted injuries that would eventually take his life-Jake De Rosier provided fodder for the thrill-mongers. De Rosier and his arch rival, Charles “Fearless” Balke, were lapping just inches apart in a closely fought match race. De Rosier was about to jump into the lead, when Balke turned his head, swerved and crashed. His Excelsior hit De Rosier who rocketed through the air, slamming against the top rail.

Dc Rosier blamed management for the crash. “If I hadn’t been compelled to go into the last heat of a race on threat of suspension,” he wrote from his hospital bed, “in order to provide sport for a manager who didn't give a cuss for me or any other rider but was looking only for the interests of the box office, I would probably be a well man today.”

De Rosier demanded reforms for his sport, namely an rule requiring helmets and goggles, higher railings and less steep banking. He also pushed for regulations that would keep Novice riders (and intoxicated Pros) off the tracks. “The time has come when something must be done to protect the lives of these (racing) men,” he argued.

Jake De Rosier never saw the changes he called for in

board-track racing. To the dismay of the motorcycle world, he died on February 25, 1913, from complications during surgery. “There was but one Jake Dc Rosier, there never will be another,” a newspaper essay said of his death, “for the conditions under which he achieved fame will never return.”

Nor would the board-tracks he once ruled. After Dc Rosier died, audiences turned away from the motordromes. World War I, the rising cost of lumber and the onset of the Great Depression all contributed to the sport’s demise.

to that the end day of when board-track arenas trembled racing can with be the traced weight back of crazed crowds and fast bikes. The day when men called “Fearless” and “Daring” commanded Cyclones and Excelsiors to triple-digit speeds. The day, September 8 of 1912, when two racers lost their lives and six spectators were killed.

The day board-track died. □

Special thanks to M.F. Egan of Vintage Motorcycles by M.F. Egati, the city of Santa Paula, California, and the Union 76 Museum for access to its excellent board-track display, “Splinter Road. ”

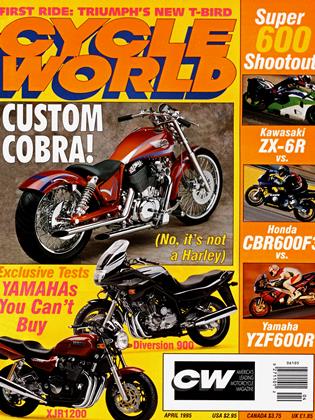

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDiversion Decision

April 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThinking Small

April 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTool Morality

April 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Rumors Are True! Yamaha's Twin Is In.

April 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia's Moto' 6.5 Comes Alive

April 1995 By Robert Hough