MEET AT THE ACE!

Outside the famous Ace Cafe in London, rockers and their cafe-racers reunite

MICK DUCKWORTH

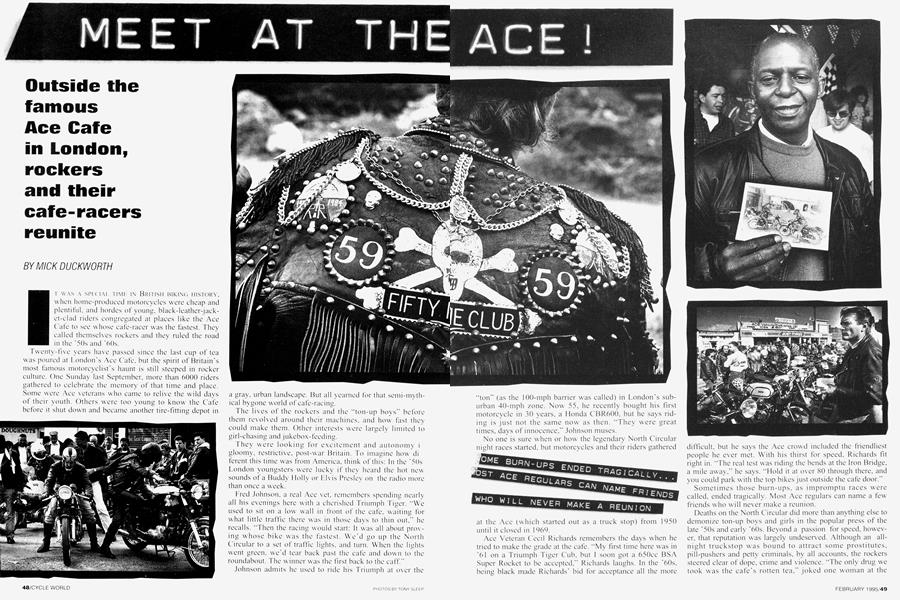

IT WAS A SPECIAL TIME IN BRITISH BIKING HISTORY, when home-produced motorcycles were cheap and plentiful, and hordes of young, black-leather-jackct-clad riders congregated at places like the Ace Cafe to see whose cafe-racer was the fastest. They called themselves rockers and they ruled the road in the '50s and '60s.

Twenty-five years have passed since the last cup of tea was poured at London’s Ace Cafe, but the spirit of Britain's most famous motorcyclist's haunt is still steeped in rocker culture. One Sunday last September, more than 6000 riders gathered to celebrate the memory of that time and place. Some were Ace veterans who came to relive the wild days of their youth. Others were too young to know the Cafe before it shut down and became another tire-fitting depot in a gray, urban landscape. But all yearned for that semi-mythical bygone world of cafe-racing.

The lives of the rockers and the “ton-up boys" before them revolved around their machines, and how fast they could make them. Other interests were largely limited to g i r 1 -c has i ng a n d ) u kebox - feed i n g.

They were looking for excitement and autonomy i gloomy, restrictive, post-war Britain. To imagine how di ferent this time was from America, think of this: In the '5()s London youngsters were lucky if they heard the hot new sounds of a Buddy Holly or Elvis Presley on the radio more than once a week.

bred Johnson, a real Ace vet, remembers spending nearly all his evenings here with a cherished Triumph Tiger. “We used to sit on a low wall in front of the cafe, waiting for what little traffic there was in those days to thin out," he recalls. “Then the racing would start: It was all about proving whose bike was the fastest. We'd go up the North Circular to a set of traffic lights, and turn. When the lights went green, we'd tear back past the cafe and down to the roundabout. The winner was the first back to the caff."

Johnson admits he used to ride his Triumph at over the “ton” (as the 100-mph barrier was called) in London's suburban 40-mph zone. Now 55. he recently bought his first motorcycle in 30 years, a Honda CBR600, but he says riding is just not the same now as then. “They were great times, days of innocence.” Johnson muses.

No one is sure when or how the legendary North Circular night races started, but motorcycles and their riders gathered

at the Ace (which started out as a truck stop) from 1950 until it closed in 1969.

Ace Veteran Cecil Richards remembers the days when he tried to make the grade at the cafe. “My first time here was in '61 on a Triumph Tiger Cub, but I soon got a 650cc BSA Super Rocket to be accepted,” Richards laughs. In the '60s, being black made Richards' bid for acceptance all the more difficult, but he says the Ace crowd included the friendliest people he ever met. With his thirst for speed, Richards fit right in. “The real test was riding the bends at the Iron Bridge, a mile away,” he says. “Hold it at over 80 through there, and you could park with the top bikes just outside the cafe door.”

Sometimes those burn-ups, as impromptu races were called, ended tragically. Most Ace regulars can name a few friends who will never make a reunion.

Deaths on the North Circular did more than anything else to demonize ton-up boys and girls in the popular press oí the late '5()s and early '60s. Beyond a passion for speed, however, that reputation was largely undeserved. Although an allnight truckstop was bound to attract some prostitutes, pill-pushers and petty criminals, by all accounts, the rockers steered clear of dope, crime and violence. “The only drug we took was the cafe’s rotten tea.” joked one woman at the reunion. As for the popular image of rockers as bad guys engaging in brawling gang rivalry? Terry Childs, an Aee customer from the early 1950s who also worked as the cafe's night manager in the 1960s, says that mutual respect, rather than lighting, was the norm. “The whole thing was about comparing our bikes, and competing in a friendly way. We talked to each other endlessly about lightening cranks, raising compression and which carburetor was best." recalls Childs.

He explains why Triumph Twins were the preferred mount for cafe-racers. “Gold Stars and Vincents were all very well, but few of us could afford them," says Childs. “Triumphs, especially the 650. could be tuned easily without spending a fortune."

Proudly wearing a leather jacket he bought in 1951. Childs ran into several old buddies at the Aee Reunion, including Cyril Malern, who now builds racecars for U.S. events.

This move into legitimate sport was typical of many Acegoers. Those w ith serious machinery would take advantage of open-to-all practice days at Brands Hatch circuit. Among Ace regulars who made a living doing the “real thing" were Dav e Croxford and Ray Piek re 11. factory riders for Norton and Triumph, respectively, in the 1970s.

Of course, not all the riding involved serious races. Aee regulars loved their pranks. Traffic police tried to maintain control on the North Circular, but their sluggish ears were often targets for cheeky stunts. One, guiltily recalled by a man nicknamed “Nobby." was to obscure his Triumph's rear registration plate w ith dirt, then prov oke a chase by rapping on the roof of a patrol ear as he accelerated past it.

But despite the patently anti-social and dangerous aspects of racing in the Ace's heyday, many of those reminiscing at the reunion returned to the theme of a lost age of innocence.

“Life was different in those days. I believe the world was a better place then. 1 wonder now w hat my kids are growing up to." worries 47-year-old Dav e Johnson. He is one of the first members of the 59 Club, a group that began in 1959 when the Reverend Bill Shergold went to the cafe and invited rockers to join his Christian youth group. Many did, and the club survives to this day.

“Father Bill" was not well enough to attend the reunion, but he sent his best wishes. His place was taken by another 59 Club leader. Father Scott Anderson, who roared up on his Kawasaki ZX-7 wearing leather and studs in addition to his clerical collar.

A police speed trap caught out some riders heading for the reunion, but the really crazy days of the North Circular hav e gone forever. Rebuilding of the road is changing it beyond recognition.

All the more reason, says Mark W ilsmore, the reunion organizer, to restore the Aee Cafe. A 37-vear-old w ith a passion for Triumph Bonnevalles. Wilsmore is too young to remember nights at the cafe w hen 300 British bikes glistened under the streetlights. But he and many others, ex-rockers and those who wish they had been, want to turn the Ace into a modern bikers' venue to pay permanent tribute to those wild, and yet in some ways so innocent, cafe-racing days. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDoctor's Orders

February 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsInvasion of the Midwestern Road Tester

February 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCWeather

February 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Tasty Trio For 1996

February 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupBmw Scraps Its Triples

February 1995 By Robert Hough