CYCLE WORLD TEST

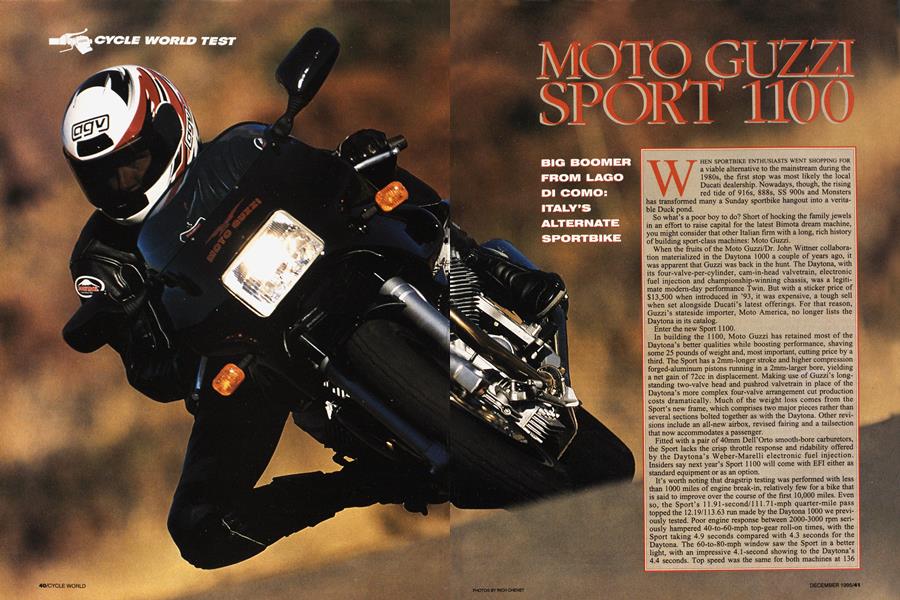

MOTO GUZZI SPORT 1100

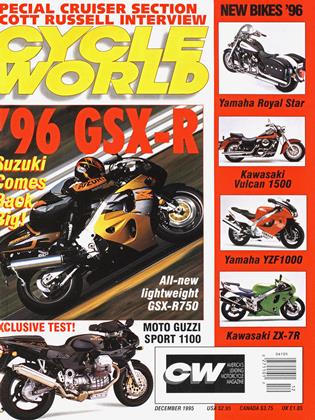

BIG BOOMER FROM LAGO DI COMO: ITALY'S ALTERNATE SPORTBIKE

WHEN SPORTBIKE ENTHUSIASTS WENT SHOPPING FOR a viable alternative to the mainstream during the 1980s, the first stop was most likely the local Ducati dealership. Nowadays, though, the rising red tide of 916s, 888s, SS 900s and Monsters has transformed many a Sunday sportbike hangout into a veritable Duck pond.

So what’s a poor boy to do? Short of hocking the family jewels in an effort to raise capital for the latest Bimota dream machine, you might consider that other Italian firm with a long, rich history of building sport-class machines: Moto Guzzi.

When the fruits of the Moto Guzzi/Dr. John Wittner collaboration materialized in the Daytona 1000 a couple of years ago, it was apparent that Guzzi was back in the hunt. The Daytona, with its four-valve-per-cylinder, cam-in-head valvetrain, electronic fuel injection and championship-winning chassis, was a legitimate modern-day performance Twin. But with a sticker price of $13,500 when introduced in ’93, it was expensive, a tough sell when set alongside Ducati’s latest offerings. For that reason, Guzzi’s stateside importer, Moto America, no longer lists the Daytona in its catalog.

Enter the new Sport 1100.

In building the 1100, Moto Guzzi has retained most of the Daytona’s better qualities while boosting performance, shaving some 25 pounds of weight and, most important, cutting price by a third. The Sport has a 2mm-longer stroke and higher compression forged-aluminum pistons running in a 2mm-larger bore, yielding a net gain of 72cc in displacement. Making use of Guzzi’s longstanding two-valve head and pushrod valvetrain in place of the Daytona’s more complex four-valve arrangement cut production costs dramatically. Much of the weight loss comes from the Sport’s new frame, which comprises two major pieces rather than several sections bolted together as with the Daytona. Other revisions include an all-new airbox, revised fairing and a tailsection that now accommodates a passenger.

Fitted with a pair of 40mm Dell’Orto smooth-bore carburetors, the Sport lacks the crisp throttle response and ridability offered by the Daytona’s Weber-Marelli electronic fuel injection. Insiders say next year’s Sport 1100 will come with EFI either as standard equipment or as an option.

It’s worth noting that dragstrip testing was performed with less than 1000 miles of engine break-in, relatively few for a bike that is said to improve over the course of the first 10,000 miles. Even , the Sport’s 11.91-second/111.71-mph quarter-mile pass topped the 12.19/113.63 run made by the Daytona 1000 we previously tested. Poor engine response between 2000-3000 rpm seriously hampered 40-to-60-mph top-gear roll-or) times, with the Sport taking 4.9 seconds compared with 4.3 seconds for the Daytona. The 60-to-80-mph window saw the Sport in a better light, with an impressive 4.1-second showing to the Daytona’s 4.4 seconds. Top speed was the same for both machines at 136 mph, the chassis displaying exceptional high-speed stability.

This stability is owed to Dr. John’s race-proven frame and quality suspension components. While the Marzocchi fork has no provision for adjusting spring preload, it does allow damping adjustments to be made on the fly. Atop each fork cap is a six-position knob the left leg controls compression damping, the right handles rebound. Likewise, the rearshock reservoirwith its seven-position compression-damping adjuster knob is located within reach of the rider and may also be varied while riding. It's truly a tinkerer's treat to have such suspension-tuning capability at your fingertips.

While there is a broad enough range of damping adjustment-there’s also an I 1-click rebound adjuster on the WP shock body-to feel a difference in ride quality, it’s not so great as to pose a risk of tuning-in an ill-handling surprise as you approach the next corner. One item that is of concern, however, is the Italian-made Bitubo steering damper located behind the bottom triple-clamp. When set toward the firm end of its 10 adjustments, it makes parking-lot maneuvers a difficult task that can easily result in a tip-over. Fact is, the Sport 1 100’s chassis stability is so good we ran the steering damper at its lightest setting throughout most of our testing without experiencing a hint of head shake.

At 58.1 inches, the Sport’s wheelbase resides on the long side of common sportbike practice. Combined with a steering-head angle of 26 degrees, 4 inches of trail and stubby, low-set clip-ons, you can bet the word “flick” isn’t in the Sport 1 100 owner’s manual. While light and twitchy handling may lend itself well to tight road work, the Guzzi’s sure-footed manner is up to the task of waltzing through most any set of curves with amazing grace.

Throw a leg over the Sport and its broad, flat saddle gives you the sense that the bike is slightly taller than its 3 1.5-inch seat height would imply. Footrest placement feels just about perfect for the mission, raised enough for adequate cornering clearance, yet not painfully so. Reach for the bars; quality CEV switchgear and nicely contoured clutch and brake levers the latter being four-position adjustable for distance out from the bar give the Guzzi rider an up-to-date interface with the machine. In an effort to quell engine vibration transmitted through the bars, the Sport comes fitted with thick foam grips and large bar-end weights. Not only did we find their spongy feel unbecoming a sportbike, the grips are a bit too narrow to accommodate riders with large hands.

Another control anomaly is the Sport's half-turn throttle. Doesn't sound like much, until you find your wrist forming a sharp “L,” with your right elbow touching your knee, only to discover you’re at half throttle.

Press the starter button and the engine cranks readily, thanks to a pair of coupled maintenance-free 12volt batteries housed under the passenger seat. Cold starts on warm California mornings required no choke and only a few blips of the throttle before the engine would sustain an idle on its own. This was fortunate, as the bar-mounted choke lever refused to remain set without a tending hand.

Twist the throttle at a standstill and the bike rocks to the right in reaction to engine flywheel effect.

Even here, the Sport has less fly weight than any other Guzzi, its flywheel/ring-gear set weighing a half-pound less than that of the Daytona. Still, with a flywheel weighing roughly twice that of a Ducati 900SS, this isn’t what you could term a snappyrevving engine. A four-finger pull on the rather stiffly sprung clutch lever delivers the jingle-ring sound of the dry clutch playing its mechanical music to the beat of the deep exhaust note exiting the twin upswept tailpipes.

Keeping the revs slightly above 3000 rpm as you slowly feed the clutch out is a must for the first launch or two of the day since there’s a buck ‘n’ stumble between 2000-3000 rpm that will surely hobble your forward progress. The condition does improve, allowing sub-2000-rpm takeoffs as the engine fully warms, yet never entirely subsides. The flat spot became less pronounced as we accumulated more miles on the motor, underscoring the famed Guzzi break-in period still, if this Guzzi were ours, first order of business would be some carb rejetting. Once the tachometer needle sweeps past 3000 rpm it’s smooth sailing, with seamless power delivery to the 8000-rpin redline and beyond.

An exaggerated left-foot movement on the long-throw shift lever changes gears with a solid, authoritative thunk that sounds as though it had to hurt. Shifting is notchy and noisy -particularly during break-in-more so than on any bike this side of a Harley Big Twin. A tender foot will easily find neutral between any of the five gears while upshifting. Drivetrain lash is greater than the norm and is not only felt, but very audible as well. While barely noticeable when riding briskly through the twisties, the eb and flow of in-town traffic evokes enough drive snatch and gear whine to rival a Willys Jeep in low range. Fortunately, unlike many shaftdrive machines, the Sport 1100’s rear doesn’t rise or fall as the throttle is dialed on and off. This is a credit to Winner's rear-suspension design, a lesson in applied geometry countering unwanted forces.

Keeping the engine between 3000-5000 rpm yields plenty of torque for city riding while serious sport duty requires revs to remain above the 5K mark. Engine vibration is quite prominent throughout the rev range, with a slight sweet spot of reduced harmonic activity at 4000 rpm and 65 mph. Aside from the need for an “Objects May Appear Greater In Number” sticker, the mirrors offer a lull-field view to the rear. Surprisingly little vibration seeps through the pegs, seat and tank, and ultimately, the Guzzi’s brand of rhythmic beating is more pleasing than it is annoying.

Once engaged in your favorite set of curves, you'll realize few bikes deliver the sense of rock-solid, road-hugging stability that is the Guzzi Sport’s forte. Cornering clearance is abundant and steering is absolutely neutral -if not quick. An asserted input through the bars in conjunction with a shift of weight achieves rapid side-to-side transitions through mediumto high-speed esses. While steering effort may check-in on the heavy end of the current sportbike scale, the Sport's uncanny case in holding a steady line through the bumpiest corner is a good tradeoff. Take trail-braking on corner entry, a situation where many bikes try to stand up while the front brake is being applied, only to drop into the corner as the brake is released. This is barely evident with the Sport.

As for straight-line braking, the twin 12.6-inch Brembo rotors and four-piston Brembo calipers deliver all the stopping power the front Michelin Hi-Sport radial can handle. Hard panic stops or normal braking over bumps didn’t bottom the fork, even when set at its lightest compression damping setting.

Chugging into your Sunday haunt aboard a Sport 1 100 makes for a genuine display of cool individuality. Deploying the Sport’s self-retracting sidestand with grace and style will require practice, though. Its forward mounting position and close proximity with the exhaust header will melt rubber boot soles as you fumble for the stand’s tang. Not cool.

Bikes are a lot like people, some of the most quirky also have the most endearing character. The more time you spend with them, the more they grow on you. Ask any firsttime Guzzi owner and he’ll probably tell you he nearly sold the bike before it was fully broken-in. He’ll also tell you he’s happy he didn’t. Our own experience with the Sport 1100 backs this up. Moto Guzzis are definitely an acquired taste-one well worth cultivating.

EDITOR'S NOTES

I’VE NEVER QUITE UNDERSTOOD ALL THIS bowing and scraping in the direction of the Guzzi factory on the shores of Lago di Como. Moto Guzzis are for old men, aren’t they?

Not the Sport 1100. This is a thoroughly modern motorcycle. Up-todate controls, great suspension and a poised chassis enable me to focus on that lump of V-Twin thundering below. Okay, the motor stumbles a bit at low speeds and the gearbox misses a few shifts. Call it the price of character. Once in its element, the 1100 turns on the charm with a composed, slow-handling manner that challenged me to think ahead, smooth out my steering inputs and make the most of that torquey motor. Good fun.

Like most potential Guzzi owners. I’m not drawn to the Sport for practical reasons. Almost $10,000 is a whole lot to pay for a bike that is easily outperformed by 600s. But if it’s a Guzzi you lust after, the Sport is the one to go for.

—Eric Putter, Associate Editor

I DON’T GET THE CHANCE TO RIDE GUZZIS very often, but each time I do the same pattern seems to transpire. The Sport 1100 being no different, I disliked its appearance and function at first. But in the end, I not only viewed it with an amiable degree of affection, I can actually see myself owning one someday.

But if I were to shell out for a Sport 1100, I'd surely keep the checkbook open and replace its Linda Blair full-twist throttle with a quarter-turn unit, fitting a set of rubber grips while I was at it. With those cheap and easy fixes, and a bit of carburetor tuning, the Sport could keep me smiling for miles and miles to come.

Oh, one other important note. With its low bars, high vibes, rear-mounted pegs and silly, spring-mounted sidestand, the Sport could never serve as my only bike-just one of my favorites. -Don Canet, Road Test Editor

FORGET FOR A MOMENT THE SWEET NOISE this Guzzi makes when the tach sweeps past 5000 rpm and the stainless-steel LaFranconi pipes start singing, disregard the crescendo of power that builds locomotive-like with each upshift... actually, you can’t-it’s like being told to go sit in a comer and not think of a pink elephant.

The Sport delivers forward motion in fat, juicy dollops, coloring all impressions of the bike. Yes, sometimes it feels like the balky gearbox requires a bribe to engage the next cog; yes, the carburetors were jetted by Lucifer himself; yes, the foam grips are junk and the annoying full-turn throttle assembly needs to be crap-canned at the first opportunity.

Hey, if ya want a refined, well-sorted machine, buy a Honda VFR750.

The Guzzi is for a different crowd. Whether that’s good or bad depends on your particular point of view. For me, the Sport 1100 remains an unfinished symphony-but that doesn’t mean I can't appreciate the beautiful music it makes. -David Edwards, Editor-in-Chief

GUZZI SPORT 1100

$9890

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontIndian Reservations

December 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCanadian Map Reading 101

December 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCJohn Britten, 1950-1995

December 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Euro-Only Sportbikes For '96

December 1995 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupHonda Steps-Up the Cbr900rr

December 1995