DUCATI UNPLUGGED

THE SINGULAR PASSIONS OF ST. HENRY

BRUCE FINLAYSON

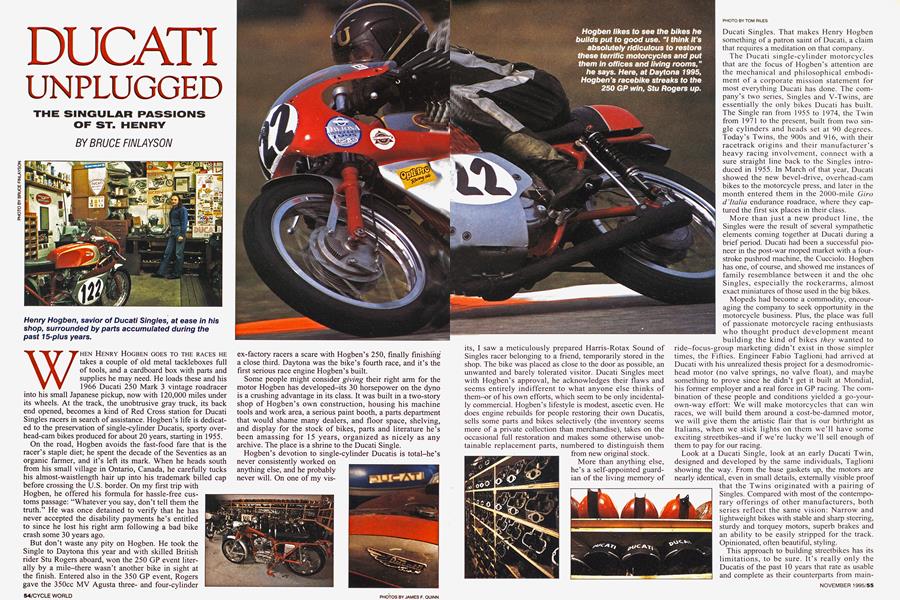

WHEN HENRY HOGBEN GOES TO THE RACES HE takes a couple of old metal tackleboxes full of tools, and a cardboard box with parts and supplies he may need. He loads these and his 1966 Ducati 250 Mark 3 vintage roadracer into his small Japanese pickup, now with 120,000 miles under its wheels. At the track, the unobtrusive gray truck, its back end opened, becomes a kind of Red Cross station for Ducati Singles racers in search of assistance. Hogben's life is dedicated to the preservation of single-cylinder Ducatis, sporty overhead-cam bikes produced for about 20 years, starting in 1955.

On the road, Hogben avoids the fast-food fare that is the racer's staple diet; he spent the decade of the Seventies as an organic farmer, and it's left its mark. When he heads south from his small village in Ontario, Canada, he carefully tucks his almost-waistlength hair up into his trademark billed cap before crossing the U.S. border. On my first trip with

Hogben, he offered his formula for hassle-free customs passage: “Whatever you say, don’t tell them the truth.’’ He was once detained to verify that he has never accepted the disability payments he’s entitled to since he lost his right arm following a bad bike crash some 30 years ago.

But don’t waste any pity on Hogben. He took the Single to Daytona this year and with skilled British rider Stu Rogers aboard, won the 250 GP event literally by a mile-there wasn’t another bike in sight at the finish. Entered also in the 350 GP event, Rogers gave the 350cc MV Agusta threeand four-cylinder

ex-factory racers a scare with Hogben’s 250, finally finishing a close third. Daytona was the bike’s fourth race, and it’s the first serious race engine Hogben’s built.

Some people might consider giving their right arm for the motor Hogben has developed-its 30 horsepower on the dyno is a crushing advantage in its class. It was built in a two-story shop of Hogben’s own construction, housing his machine tools and work area, a serious paint booth, a parts department that would shame many dealers, and floor space, shelving, and display for the stock of bikes, parts and literature he’s been amassing for 15 years, organized as nicely as any archive. The place is a shrine to the Ducati Single.

Hogben’s devotion to single-cylinder Ducatis is total-he’s never consistently worked on anything else, and he probably never will. On one of my vis-

its, I saw a meticulously prepared Harris-Rotax Sound of Singles racer belonging to a friend, temporarily stored in the shop. The bike was placed as close to the door as possible, an unwanted and barely tolerated visitor. Ducati Singles meet with Hogben’s approval, he acknowledges their flaws and seems entirely indifferent to what anyone else thinks of them-or of his own efforts, which seem to be only incidentally commercial. Hogben’s lifestyle is modest, ascetic even. He does engine rebuilds for people restoring their own Ducatis, sells some parts and bikes selectively (the inventory seems more of a private collection than merchandise), takes on the occasional full restoration and makes some otherwise unobtainable replacement parts, numbered to distinguish them

from new original stock.

More than anything else, he’s a self-appointed guardian of the living memory of

Ducati Singles. That makes Henry Hogben something of a patron saint of Ducati, a claim that requires a meditation on that company.

The Ducati single-cylinder motorcycles that are the focus of Hogben’s attention are the mechanical and philosophical embodiment of a corporate mission statement for most everything Ducati has done. The company’s two series, Singles and V-Twins, are essentially the only bikes Ducati has built. The Single ran from 1955 to 1974, the Twin from 1971 to the present, built from two single cylinders and heads set at 90 degrees. Today’s Twins, the 900s and 916, with their racetrack origins and their manufacturer’s heavy racing involvement, connect with a sure straight line back to the Singles introduced in 1955. In March ofthat year, Ducati showed the new bevel-drive, overhead-cam bikes to the motorcycle press, and later in the month entered them in the 2000-mile Giro d’Italia endurance roadrace, where they captured the first six places in their class.

More than just a new product line, the Singles were the result of several sympathetic elements coming together at Ducati during a brief period. Ducati had been a successful pioneer in the post-war moped market with a fourstroke pushrod machine, the Cucciolo. Hogben has one, of course, and showed me instances of family resemblance between it and the ohc Singles, especially the rockerarms, almost exact miniatures of those used in the big bikes.

Mopeds had become a commodity, encouraging the company to seek opportunity in the motorcycle business. Plus, the place was full of passionate motorcycle racing enthusiasts who thought product development meant building the kind of bikes they wanted to

ride-focus-group marketing didn’t exist in those simpler times, the Fifties. Engineer Fabio Taglioni had arrived at Ducati with his unrealized thesis project for a desmodromichead motor (no valve springs, no valve float), and maybe something to prove since he didn’t get it built at Mondial, his former employer and a real force in GP racing. The combination of these people and conditions yielded a go-yourown-way effort: We will make motorcycles that can win races, we will build them around a cost-be-damned motor, we will give them the artistic flair that is our birthright as Italians, when we stick lights on them we’ll have some exciting streetbikes-and if we’re lucky we’ll sell enough of them to pay for our racing.

Look at a Ducati Single, look at an early Ducati Twin, designed and developed by the same individuals, Taglioni showing the way. From the base gaskets up, the motors are nearly identical, even in small details, externally visible proof

that the Twins originated with a pairing of Singles. Compared with most of the contemporary offerings of other manufacturers, both series reflect the same vision: Narrow and lightweight bikes with stable and sharp steering, sturdy and torquey motors, superb brakes and an ability to be easily stripped for the track. Opinionated, often beautiful, styling.

This approach to building streetbikes has its limitations, to be sure. It’s really only the Ducatis of the past 10 years that rate as usable and complete as their counterparts from main-

stream manufacturers. They certain ly had their limitations in 1964 when Hogben, then a mechanic at a Honda dealership and owner of a 1958 BSA Golden Flash, saw the Cycle World

road test of the new 250 Mark 3. Top speed was 104 mph, faster than most 500s; it was light, it was beautiful. He canceled his order for a 250cc Honda CB72, and took delivery of a new Mark 3 in a crate.

Hogben wanted a streetbike he could race. He found track time at Harewood, an Ontario airfield circuit, by going out on days when the place was deserted, slipping out onto the track through an opening in the fence. Simpler times, indeed. Hogben did some mild engine work, discovering “blue-printing” for himself before its benefits had become widely appreciated. He became a very fast rider, achieving his best performance early in the 1965 season when he finished first in his class in the Canadian Championship Cup.

But Hogben’s promising start in roadracing was cruelly cut short on Labor Day weekend in 1965, when he tried a BSA hillclimber and it got away from him, leaving him with severe injuries that resulted in the loss of his arm. Resourceful by nature, he persisted as a mechanic, gaining back with methodical intelligence what he gave up in speed as he adapted a new style of working. He tried university, excelling in math and science, but really had his mind opened by the counterculture attitudes he found around school at that time.

“It all made so much sense to me,” Hogben says. “I’d watched my father give his life to an automobile plant. I’d feared that was my destiny too, one I couldn’t countenance because the big car company was a sort of symbol to me of a world in the grip of mindless consumption and waste. I guess you could say I became a hippie.”

It was a life turning point, the effects of which remain with Hogben today.

“I didn’t fully realize it then,” he says, “but I might be one of those people who were born into the wrong century. I’d much rather have taken my chances in the wild, where life had a genuine center of gravity and the forces you dealt with-the seasons, predators and so forth-were the wellspring of life, instead of a 20th-century urban existence which I find entirely synthetic and frankly quite petty. I’ve made my own little bubble here in this tiny village, I’m removed from the establishment, though I enjoy many of the people I meet through my work.”

Like many of today’s middle-aged motorcyclists, Hogben put bikes in a closet during his late 20s and much of his 30s, though he never got far away from the abilities that lie

behind his achievements with Ducati Singles today. He picked up a neglected '59 Chevy panel truck, carried out a frame-off restoration (“I wire-wheeled every nut and bolt on that truck”) and set off for British Columbia. In a fishing village north of Vancouver, he came to the rescue of an abandoned 42foot wooden fishpacker, Chatham Point, and spent a year there restoring it.

But the back-to-nature, selfsufficiency call he'd heard around university was strong, and Hogben took himself up to the Alaska Panhandle, where for

a time he lived much as some of the indigenous Indian tribes there still do. “I sort of fell into farming there, but the conditions were hopeless,” he recalls. Returning east, he bought 200 acres in the bush in Quebec, near a stretch of the Gatineau River. There, Hogben cleared some of his property and farmed it with the aid of a couple of long-neglected tractors he found and restored, a 1942 Allis-Chalmers and a, 1958 International Harvester. Eventually he had 40 acres in hay for his animals, and tilled another 15 acres in crops.

“I’ve always been a neat freak,” Hogben says, “and while you can’t be as fussy with a farm as you can with a little Ducati, there pretty much wasn’t a weed on the place.”

The work was strenuous and endless; it was years before he finished clearing and grading a drive to the nearest road, three miles away.

“On a trip back home for Christmas in 1981, after 10 years on the farm, I went to look at a couple of Ducati Singles and bought them,” Hogben remembers. “I really don’t know why. Then, back at the farm, I kept thinking about those bikes, and about how I was just wearing myself out there.”

Soon the farm was sold and Hogben found himself crisscrossing North America uncovering Ducati Singles stock and selectively acquiring what he wanted. He chose a 1974 450 as his own ride, fabricating left-hand controls and fashioning linked braking from the pedal, with adjustable frontrear proportioning. He completed his first restoration in 1990, a 1966 Mach 1-otherwise finished a couple of years earlier, it was held back while he sourced the correct fabric from which he could sew the seat cover.

Henry Hogben does it all, and he does it his way, with his own unique sense of purpose and ruthlessly high standards. Is it ironic that his mission, so little concerned with worldly interests, results in the world-at least a small and enthusiastic part of it-beating a path to his door? Well, no more ironic than the current success enjoyed by Ducati, whose heritage lies in his and a few others’ capable hands. That company has been bom again by reaffirming its very individual origins in a stubbornly nationalistic definition of motorcycle purpose, only slightly altered by technology. This approach, like Hogben’s, is the hard way to do it, carries no guarantees of commercial success, and takes a special breed of people to pull off. The next time your head is turned by one of these charismatic motorcycles, think of the passionate individualists responsible for their existence.

Think of St. Henry. E3

Bruce Finlayson, an industrial designer in Madison, Wisconsin, roadraced Ducati Singles in the 1960s. For more on that, see the accompanying story.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

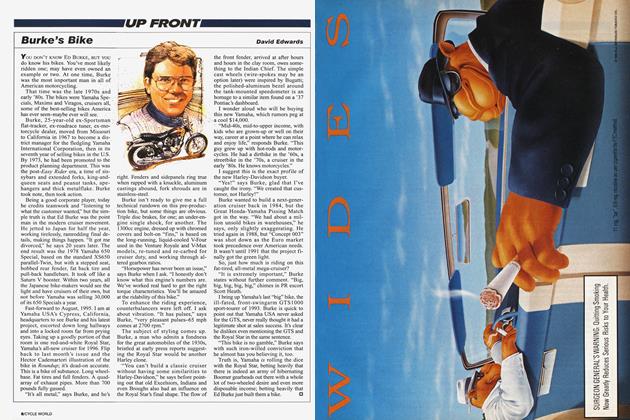

Up FrontBurke's Bike

November 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCafe Racing

November 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCExtremes

November 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1995 -

Special Section

Special SectionCalifornia Specials

November 1995 By Jon F. Thompson -

California Specials

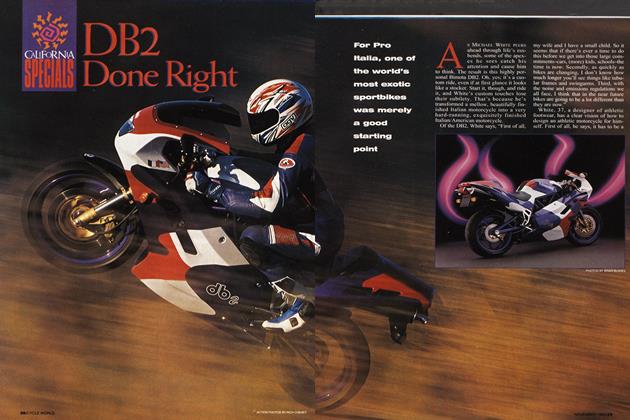

California SpecialsDb2 Done Right

November 1995 By Jon F. Thompson