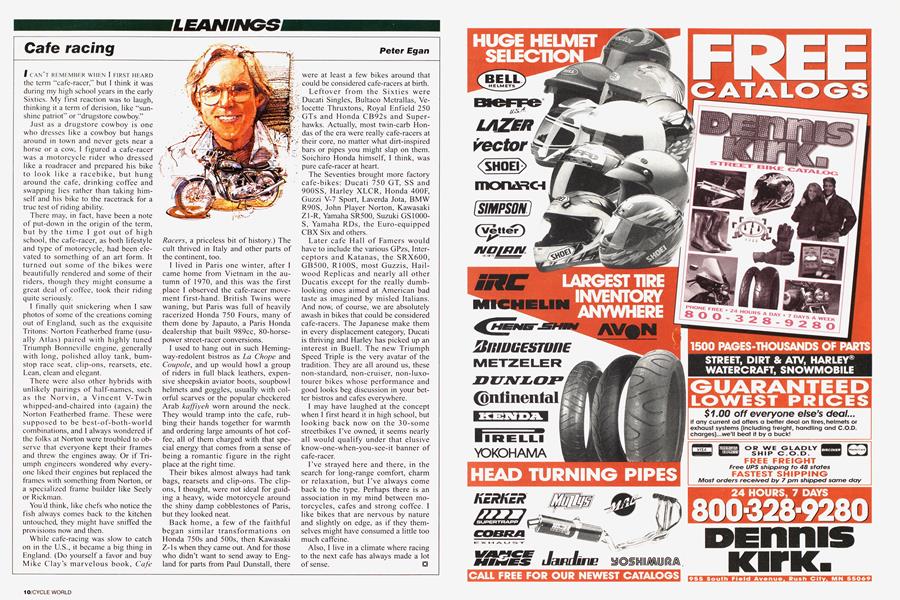

Cafe racing

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

I CAN’T REMEMBER WHEN I FIRST HEARD the term “cafe-racer,” but I think it was during my high school years in the early Sixties. My first reaction was to laugh, thinking it a term of derision, like “sunshine patriot” or “drugstore cowboy.”

Just as a drugstore cowboy is one who dresses like a cowboy but hangs around in town and never gets near a horse or a cow, I figured a cafe-racer was a motorcycle rider who dressed like a roadracer and prepared his bike to look like a racebike, but hung around the cafe, drinking coffee and swapping lies rather than taking him-self and his bike to the racetrack for a true test of riding ability.

There may, in fact, have been a note of put-down in the origin of the term, but by the time I got out of high school, the cafe-racer, as both lifestyle and type of motorcycle, had been elevated to something of an art form. It turned out some of the bikes were beautifully rendered and some of their riders, though they might consume a great deal of coffee, took their riding quite seriously.

I finally quit snickering when I saw photos of some of the creations coming out of England, such as the exquisite Tritons: Norton Featherbed frame (usually Atlas) paired with highly tuned Triumph Bonneville engine, generally with long, polished alloy tank, bumstop race seat, clip-ons, rearsets, etc. Lean, clean and elegant.

There were also other hybrids with unlikely pairings of half-names, such as the Norvin, a Vincent V-Twin whipped-and-chaired into (again) the Norton Featherbed frame. These were supposed to be best-of-both-world combinations, and I always wondered if the folks at Norton were troubled to observe that everyone kept their frames and threw the engines away. Or if Triumph engineers wondered why everyone liked their engines but replaced the frames with something from Norton, or a specialized frame builder like Seely or Rickman.

You’d think, like chefs who notice the fish always comes back to the kitchen untouched, they might have sniffed the provisions now and then.

While cafe-racing was slow to catch on in the U.S., it became a big thing in England. (Do yourself a favor and buy Mike Clay’s marvelous book, Cafe

Racers, a priceless bit of history.) The cult thrived in Italy and other parts of the continent, too.

I lived in Paris one winter, after I came home from Vietnam in the autumn of 1970, and this was the first place I observed the cafe-racer movement first-hand. British Twins were waning, but Paris was full of heavily racerized Honda 750 Fours, many of them done by Japauto, a Paris Honda dealership that built 989cc, 80-horsepower street-racer conversions.

I used to hang out in such Hemingway-redolent bistros as La Chope and Coupole, and up would howl a group of riders in full black leathers, expensive sheepskin aviator boots, soupbowl helmets and goggles, usually with colorful scarves or the popular checkered Arab kaffiyeh worn around the neck. They would tramp into the cafe, rubbing their hands together for warmth and ordering large amounts of hot coffee, all of them charged with that special energy that comes from a sense of being a romantic figure in the right place at the right time.

Their bikes almost always had tank bags, rearsets and clip-ons. The clipons, I thought, were not ideal for guiding a heavy, wide motorcycle around the shiny damp cobblestones of Paris, but they looked neat.

Back home, a few of the faithful began similar transformations on Honda 750s and 500s, then Kawasaki Z-ls when they came out. And for those who didn’t want to send away to England for parts from Paul Dunstall, there

were at least a few bikes around that could be considered cafe-racers at birth.

Leftover from the Sixties were ; Ducati Singles, Bultaco Metrallas, Ve•vlocette Thruxtons, Royal Enfield 250 GTs and Honda CB92s and Superhawks. Actually, most twin-carb Hondas of the era were really cafe-racers at their core, no matter what dirt-inspired bars or pipes you might slap on them. Soichiro Honda himself, I think, was pure cafe-racer at heart.

The Seventies brought more factory cafe-bikes: Ducati 750 GT, SS and 900SS, Harley XLCR, Honda 400F, Guzzi V-7 Sport, Laverda Jota, BMW R90S, John Player Norton, Kawasaki Zl-R, Yamaha SR500, Suzuki GS1000S, Yamaha RDs, the Euro-equipped CBX Six and others.

Later cafe Hall of Famers would have to include the various GPzs, Interceptors and Katanas, the SRX600, GB500, R100S, most Guzzis, Hailwood Replicas and nearly all other Ducatis except for the really dumblooking ones aimed at American bad taste as imagined by misled Italians. And now, of course, we are absolutely awash in bikes that could be considered cafe-racers. The Japanese make them in every displacement category, Ducati is thriving and Harley has picked up an interest in Buell. The new Triumph Speed Triple is the very avatar of the tradition. They are all around us, these non-standard, non-cruiser, non-luxotourer bikes whose performance and good looks beg discussion in your better bistros and cafes everywhere.

I may have laughed at the concept when I first heard it in high school, but looking back now on the 30-some streetbikes I’ve owned, it seems nearly all would qualify under that elusive know-one-when-you-see-it banner of cafe-racer.

I’ve strayed here and there, in the search for long-range comfort, charm or relaxation, but I’ve always come back to the type. Perhaps there is an association in my mind between motorcycles, cafes and strong coffee. I like bikes that are nervous by nature and slightly on edge, as if they themselves might have consumed a little too much caffeine.

Also, I live in a climate where racing to the next cafe has always made a lot of sense.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBurke's Bike

November 1995 By David Edwards -

TDC

TDCExtremes

November 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1995 -

Special Section

Special SectionCalifornia Specials

November 1995 By Jon F. Thompson -

California Specials

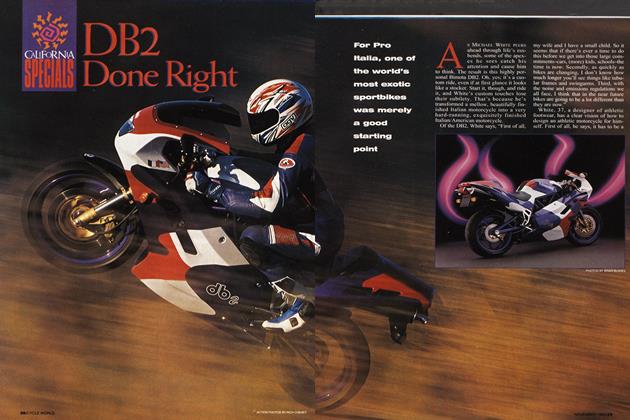

California SpecialsDb2 Done Right

November 1995 By Jon F. Thompson -

California Specials

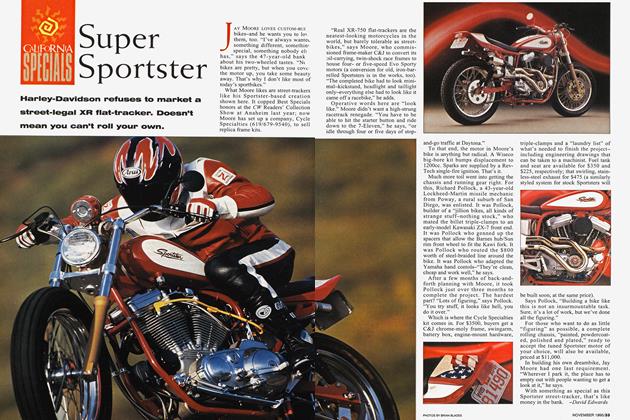

California SpecialsSuper Sportster

November 1995 By David Edwards