Fun and Fatigue in France

RACE WATCH

Beat senseless by the world's toughest race

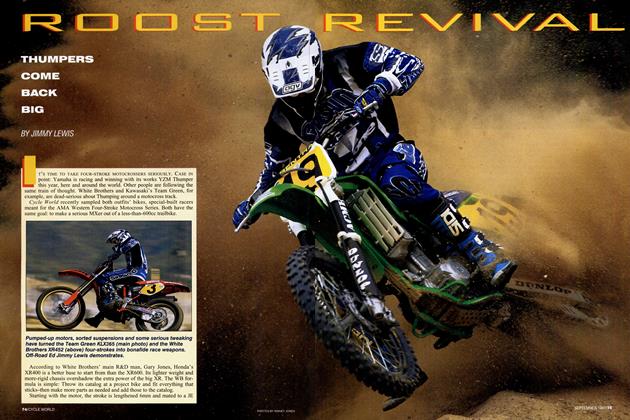

JIMMY LEWIS

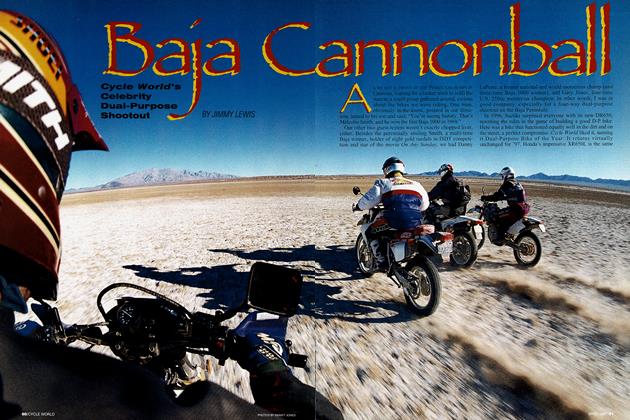

IT SEEMED EASY: FLY TO FRANCE, ride the Gilles Lalay Classic, finish in the top 10, come home. No problem, right? Wrong. Hey, I like challenges, but this is ridiculous. The GLC, as it’s called, is named after a French racing hero killed in the 1992 Paris-to-Dakar Rally, and is a combination of enduro, rally and endurance race. It takes place in central France, in the hills surrounding Limoge, Lalay’s home town, and it is second only to the International Six Days Enduro in importance to the European off-road racing community. Not for nothing is it called the world’s toughest race.

I didn’t care. I managed to finagle an entry for the GLC and support from the Castex Racing Department, or CRD, the official Suzuki racing team in France, which prepared a Suzuki RM250, complete with lights, for my use.

The GLC attracts the Who’s Who of the World Enduro scene. The first GLC, run in foot-deep snow, was conquered by just 21 riders, with Sweden’s Sven-Eric Jonsson taking the win. For the second race, the promoters increased the difficulty of the route. Nature helped by providing a coating of ice and more snow. This brought the finisher’s list down to 15, again led by Jonsson. Consider that there were more than 200 starters, and you begin to get the notion that this race is a little difficult to finish.

The course for this third GLC comprised two parts. The morning was formatted like a typical European enduro, in which each rider has a predetermined time to clear sections, racing through special-test sections

for scoring. The afternoon and night sections are designed as what the French call a scratch race, in which the first person to the finish line wins. Each section measured 200 kilometers, or 124.2 miles. No problem. Maybe. As I tried to sleep the night before the race, I thought of the horror photos from past GLC eventsspectators chaining themselves together to pull riders and bikes up the hills, rock piles that would scare off trials riders, cold, wet gear to go along with the mud, roots, rocks and hills. Was I ready? Was I in good enough shape? Could I finish? Zzzz....

....Buuzzzzz! I jumped awake from a light and restless sleep. It was 5 a.m., pitch-black outside, but the starting area was crawling with racers and fans, the first sign of the committed craziness of French spectators.

I was number 55, with a 6:45 start time. The route took us into Limoge’s old city, and from there to Peyrat Le Chateau, where the scratch race would take place. I’ve ridden at night before, but never in mud. Three months of constant rain in the region had created plenty of this. So as soon as we hit the edge of town I found myself at the bottom of a learning curve with a sharply rising arc. I plugged along, passing stuck riders and staying on time. As dawn broke and the sun peeked over the eastern horizon, I was confident that I could keep this pace until midnight, 15 hours away. I ripped through the first special test, placing 20th overall. I was well on my way to qualifying for the night event.

Then I began encountering some of the stumbling blocks on the way to Peyrat Le Chateau, the ones that gave the GLC its reputation. I found steep hills and tight, tree-lined trails connected by farm roads to more tight trails that wound through, past and over rocks, hills, rivers and mud.

Then there was The Step, an eroded 10-foot cliff face that had become a bottleneck. I arrived behind six or seven riders, and, alerted to the lack of uphill traction by a slithering bike and a wildly spinning rear tire, hopped off the bike and grabbed a tree. With my free hand I tried to stabilize the bike on the 45-degree slope, and awaited my turn to drag my bike up the hill. There were two spectators helping each rider up the face of roots and rocks. As I watched the hill get worse, the helpers got increasingly tired, and my chances of making it to the next check on time faded away.

Ah, well, at least this hill would be as bad as it got for the morning’s race. Wouldn’t it? Nope. The trail kept getting tougher as it clawed its way up a river, off a cliff, into the mud. The section was topped by a final piece of agony, a 4-mile special test obviously designed to stimulate pre-finish exhaustion. I finished 14 minutes late, putting fear into my heart, right there next to that tired feeling, that I might not make the afternoon race. After an hour-and-a-half wait, JeanPaul Castex, my mechanic, shook me awake to tell me I was one of the 70 riders who managed to qualify for the afternoon section.

I was feeling a lot better as I lined up at a motocross starting gate set up on a grass track. I was in the second

wave, set to take-off one minute after the fastest guys, and to be followed by another wave of slower riders.

It was important to get a good start here, but when the gate dropped, I found myself battling for position in a blizzard of roost. I noticed a competitor on a trials bike go around me on the outside. A few factory trials riders had entered thinking their light, agile bikes might hold the keys to finishing the GLC. The deep mud had those same riders thinking again.

For the next couple of miles I passed groups of riders at various bogs and river crossings, where I slithered through by picking choice lines and staying on the gas. By now I had passed a bunch of riders, and here, towards the front of the pack, the route was not quite so torn up.

Not, at least, until one little river crossing. I slammed in and found my bike gripped by the sort of mud that makes sucking noises when you try to pull your boot out of it. It grabbed my bike, sucked it to the center of the Earth, and secured it there with an array of hooked, gnarled tree roots. I pinned the throttle and bounced up and down, much to the delight of the gang of fans gathered here. They let me struggle for a few seconds, then jumped into the mud to pull the stuck Suzuki free.

From here I adopted a new approach. Instead of going flat-out, I would ride at maybe eight-tenths, conserving the energy I had for the long run. Things went fine until I came to The Mudhill. It looked like a dirtbike convention at which, because of steepness, slickness and tiredness, nobody could stand up. A throng of about 1000 spectators was working together to pull the riders to the top. I gave it my best run and managed to pass a few on the way up, dodge a few on their way down and get stuck right where the rest of the bikes were parked waiting for the Human Towing Service to make a call.

Ten minutes in line and it was my turn. Five sweating, grunting Frenchmen, connected to the top of the hill by nearly 100 others who held onto the first five through a writhing human chain, grabbed my bike. I started the RM and helped by spinning the rear wheel, throwing up a roost that covered the riders below me in mud, just as I had been covered by the roosts of those ahead of me. As I slowly was pulled over the top I saluted my helper with a clenched fist, noticed the incredible amount of steam coming out of the radiator overflow, and barely had time to put my hand back on the bar to careen down the cliff just past the mudhill’s apex-and right into the lake at the bottom. I followed the course around the side of the lake until my bike overheated, then used my glove as a makeshift canteen to refill the radiator.

Uphill, downhill I went for a few more miles until I came across the biggest mud bog so far. I threw my hands up in the air to signal the people on the other side of the bog to show me the best line. They did, I took it, and got stuck. Before I could roll out of the throttle, one of the spectators was pushing me out. We managed to

get to the edge only after my spinning rear knobby launched black, goopy roost all over my helper, a woman in her 40s. I turned to say thanks, and she cracked a smile that showed me she had mud even in her teeth.

Is the worst over? Not a chance. The course now made its way up a steep cliff. I launched my now-frazzled body and bike up the cliff’s face, hooked the front wheel over the top and barely hung on to stay there. A couple of other riders were there, absorbed in their own problems. I looked around to see where the trail went, and verified my worst fears. A course arrow indicated that it went straight up another cliff. “I think I can, I think I can,” I muttered to myself. I launched again, scrabbled over the top, and found myself looking at The World’s Biggest Bog, a half-mile long mess of mud presided over by a crowd of spectators comfortably staked out on a hill. I screwed up my courage, screwed on the gas, and about halfway across, slowly started sinking. I jumped off the bike to begin pushing and quickly I, too, began sinking. No choice: I let go of the bike and lay down to slow the process. I was as stuck as the bike. A couple of fans made their way over to me and helped me pull my legs out of the putty. My bike had to be rocked back and forth and then laid over and dragged to firmer mud. By the time the extraction was complete, I was wasted, and feeling the cold grip of defeat. The first gas stop had to be close, and I wanted to make it at least that far.

I rounded a corner in the forest to find hundreds of people arrayed around a huge pile of rocks. There seemed no possible path through the rocks, but people were pointing. Before I knew what was happening a guy had put a tie strap around my bike’s fork and, aided by friends, began towing me up the rocks. I started to fall and hands came out of the crowd to provide balance. My helpers tugged me to the top and also tugged the remainder of energy out of my body. As the tie was unhooked a spectator with a camera yelled out, “Hey, Américain, what do you sink of zee French Riviera?”

I gave the group a thumbs-up and began to admit that the GLC just about had me beat. I saw the scraped-up knuckles and knees these fans had as their rewards for helping riders. One of them had a good sized welt on his head. I had to appreciate the enthusiasm these people had, and this esprit de corps gave me the push to keep going. Or maybe it was just the fear of the crowd turning wild on a quitter.

I made it to the first gas just as my bike sputtered on an empty tank, just as my body seized. 1 was stumbling like a drunk and I’m not sure my mind was working all that well. I must have had one flash of common sense, though, because 1 realized that if I got stuck anywhere else, there wouldn’t be anyone to help me out, because by now all the spectators had either moved on, or were too exhausted to do anything but watch. I hate to say it, but I quit. I was finished.

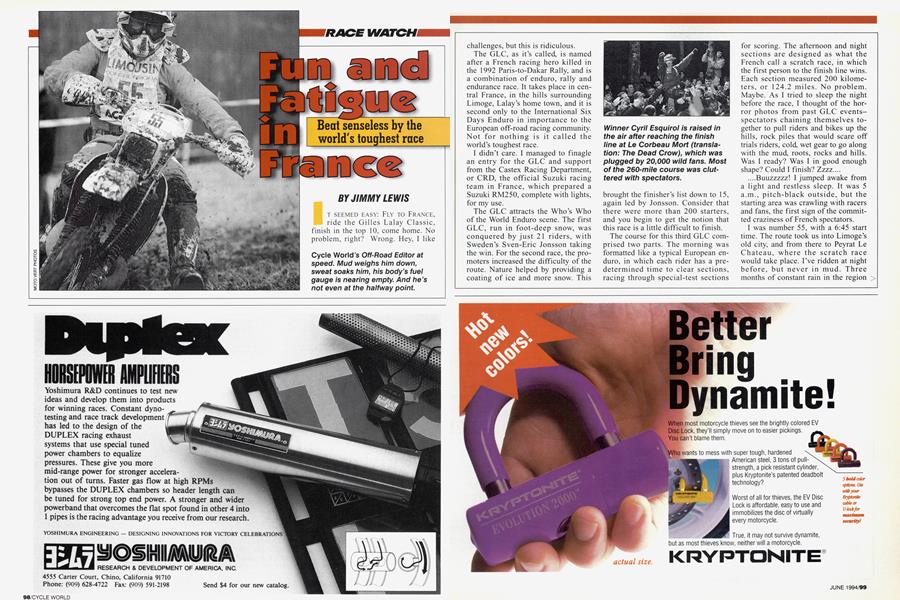

So were lots of others. Two-hundred and seventeen riders started the Gilles Lalay Classic. Nine finished. Frenchman Cyril Esquirol was carried over the top of the last hill by some of the 20,000 spectators at the finish to take the GLC trophy away from past champion Jonsson, who finished second, 10 minutes down. Esquirol finished at 10 p.m., 16 hours after the start. Alain Olivier, winner of last year’s inaugural Nevada Rally, finished third.

I’m not sure of the ultimate goal for this race, but if it is to put over-confident Off-Road Editors in their place, or to show the world what a tough off-road race is really like, I’ve got to conclude this: The Gilles Lalay Classic is a winner. □