HONDA V-FOURS

A LOOK AT THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF A LATTER-DAY LEGACY

KEVIN CAMERON

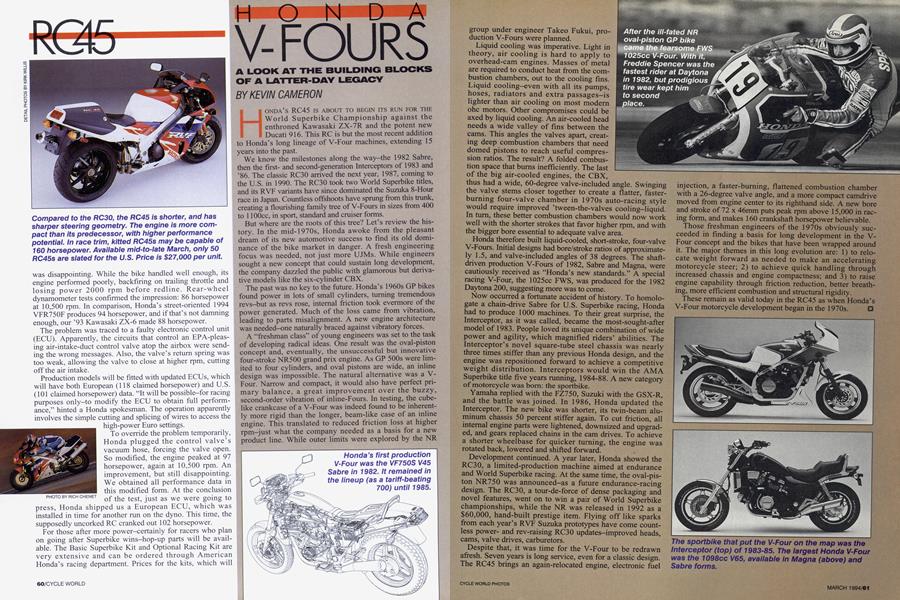

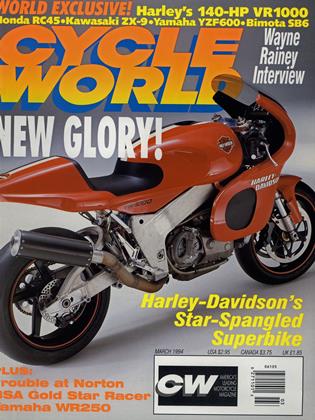

HONDA'S RC45 IS ABOUT TO BEGIN ITS RUN FOR THE World Superbike Championship against the enthroned Kawasaki ZX-7R and the potent new Ducati 916. This RC is but the most recent addition to Honda's long lineage of V-Four machines, extending 15 years into the past.

We know the milestones along the way-the 1982 Sabre, then the firstand second-generation Interceptors of 1983 and ’86. The classic RC30 arrived the next year, 1987, coming to the U.S. in 1990. The RC30 took two World Superbike titles, and its RVF variants have since dominated the Suzuka 8-Hour race in Japan. Countless offshoots have sprung from this trunk, creating a flourishing family tree of V-Fours in sizes from 400 to 1 lOOcc, in sport, standard and cruiser forms.

But where are the roots of this tree? Let’s review the history. In the mid-1970s, Honda awoke from the pleasant dream of its new automotive success to find its old dominance of the bike market in danger. A fresh engineering focus was needed, not just more UJMs. While engineers sought a new concept that could sustain long development, the company dazzled the public with glamorous but derivative models like the six-cylinder CBX.

The past was no key to the future. Honda’s 1960s GP bikes found power in lots of small cylinders, turning tremendous revs-but as revs rose, internal friction took evermore of the power generated. Much of the loss came from vibration, leading to parts misalignment. A new engine architecture was needed-one naturally braced against vibratory forces.

A “freshman class” of young engineers was set to the task of developing radical ideas. One result was the oval-piston concept and, eventually, the unsuccessful but innovative four-stroke NR500 grand prix engine. As GP 500s were limited to four cylinders, and oval pistons are wide, an inline design was impossible. The natural alternative was a VFour. Narrow and compact, it would also have perfect primary balance, a great improvement over the buzzy, second-order vibration of inline-Fours. In testing, the cubelike crankcase of a V-Four was indeed found to be inherently more rigid than the longer, beam-like case of an inline engine. This translated to reduced friction loss at higher rpm-just what the company needed as a basis for a new product line. While outer limits were explored by the NR group under engineer Takeo Fukui, production V-Fours were planned.

Liquid cooling was imperative. Light in theory, air cooling is hard to apply to overhead-cam engines. Masses of metal are required to conduct heat from the combustion chambers, out to the cooling fins.

Liquid cooling—even with all its pumps, hoses, radiators and extra passages-is lighter than air cooling on most modem ohc motors. Other compromises could be axed by liquid cooling. An air-cooled head needs a wide valley of fins between the cams. This angles the valves apart, creating deep combustion chambers that need domed pistons to reach useful compression ratios. The result? A folded combustion space that bums inefficiently. The last of the big air-cooled engines, the CBX,

thus had a wide, 60-degree valve-included angle. Swinging the valve stems closer together to create a flatter, fasterburning four-valve chamber in 1970s auto-racing style would require improved ’tween-the-valves cooling-liquid. In turn, these better combustion chambers would now work well with the shorter strokes that favor higher rpm, and with the bigger bore essential to adequate valve area.

Honda therefore built liquid-cooled, short-stroke, four-valve V-Fours. Initial designs had bore/stroke ratios of approximately 1.5, and valve-included angles of 38 degrees. The shaftdriven production V-Fours of 1982, Sabre and Magna, were cautiously received as “Honda’s new standards.” A special racing V-Four, the 1025cc FWS, was produced for the 1982 Daytona 200, suggesting more was to come.

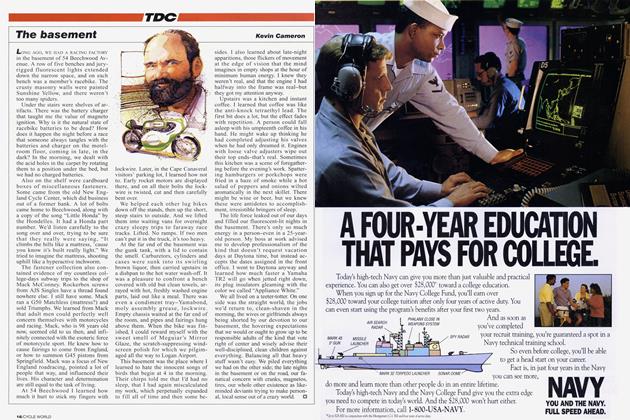

Now occurred a fortunate accident of history. To homologate a chain-drive Sabre for U.S. Superbike racing, Honda had to produce 1000 machines. To their great surprise, the Interceptor, as it was called, became the most-sought-after model of 1983. People loved its unique combination of wide power and agility, which magnified riders’ abilities. The Interceptor s novel square-tube steel chassis was nearly three times stiffer than any previous Honda design, and the engine was repositioned forward to achieve a competitive weight distribution. Interceptors would win the AMA Superbike title five years mnning, 1984-88. A new category of motorcycle was bom: the sportbike.

Yamaha replied with the FZ750, Suzuki with the GSX-R, and the battle was joined. In 1986, Honda updated the Interceptor. The new bike was shorter, its twin-beam aluminum chassis 50 percent stiffer again. To cut friction, all internal engine parts were lightened, downsized and upgraded, and gears replaced chains in the cam drives. To achieve a shorter wheelbase for quicker turning, the engine was rotated back, lowered and shifted forward.

Development continued. A year later, Honda showed the RC30, a limited-production machine aimed at endurance and World Superbike racing. At the same time, the oval-piston NR7 50 was announced-as a future endurance-racing design. The RC30, a tour-de-force of dense packaging and novel features, went on to win a pair of World Superbike championships, while the NR was released in 1992 as a $60,000, hand-built prestige item. Flying off like sparks from each year’s RVF Suzuka prototypes have come countless powerand rev-raising RC30 updates—improved heads, cams, valve drives, carburetors.

Despite that, it was time for the V-Four to be redrawn afresh. Seven years is long service, even for a classic design. The RC45 brings an again-relocated engine, electronic fuel

injection, a faster-burning, flattened combustion chamber with a 26-degree valve angle, and a more compact camdrive moved from engine center to its righthand side. A new bore and stroke of 72 x 46mm puts peak rpm above 15,000 in racing form, and makes 160 crankshaft horsepower believable.

Those freshman engineers of the 1970s obviously succeeded in finding a basis for long development in the VFour concept and the bikes that have been wrapped around it. The major themes in this long evolution are: 1) to relocate weight forward as needed to make an accelerating motorcycle steer; 2) to achieve quick handling through increased chassis and engine compactness; and 3) to raise engine capability through friction reduction, better breathing, more efficient combustion and structural rigidity.

These remain as valid today in the RC45 as when Honda’s V-Four motorcycle development began in the 1970s. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue