Wild Bill rests

UP FRONT

David Edwards

You CAN’T SAY WILD BILL DIDN’T GO out in style. William Clement Cottom died last November, 86 years old, and in accordance with his last wishes, he was cremated then interred in the fuel tank of his beloved 1952 Vincent Black Lightning. Certainly, no man ever had a finer funeral urn.

Cottom was born in 1907 on a farm in Kansas. He rode his first motorcycle at age 12 when an older cousin stopped by on his new belt-drivé Reading-Standard. Given a rudimentary rundown of the machine’s various levers, pulleys and hand pumps, young Bill managed to get underway without tipping over or stalling. He did not return for four hours.

Laying the foundation for a work ethic that would serve him well throughout life, high-schooler Cottom was already employed part-time in a general store when he opened a gym and learned how to box. He became good enough to win the Kansas lightheavyweight championship in 1924, but at 17 he was underage, and tippedoff officials took away the title within 24 hours, though he got to keep the $700 prize money.

With money saved from the general store and boxing, Cottom purchased a new Harley-Davidson. When the Depression hit a few years later, he loaded up the Harley and rode it to Chicago, where he worked as a sparring partner for $1 a round during the day and raced the Harley on boardtracks and flat-tracks at night. It was from these exploits that Cottom picked up his nickname.

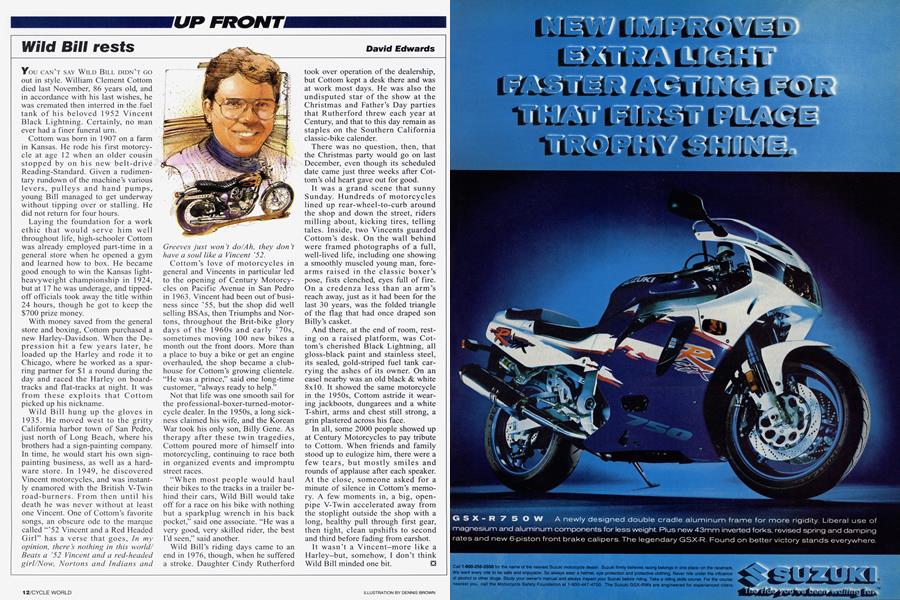

Wild Bill hung up the gloves in 1935. He moved west to the gritty California harbor town of San Pedro, just north of Long Beach, where his brothers had a sign-painting company. In time, he would start his own signpainting business, as well as a hardware store. In 1949, he discovered Vincent motorcycles, and was instantly enamored with the British V-Twin road-burners. From then until his death he was never without at least one Vincent. One of Cottom’s favorite songs, an obscure ode to the marque called “’52 Vincent and a Red Headed Girl” has a verse that goes, In my opinion, there’s nothing in this world/ Beats a ’52 Vincent and a red-headed girl/Now, Nortons and Indians and Greeves just won’t do/Ah, they don’t have a soul like a Vincent ’52.

Cottom’s love of motorcycles in general and Vincents in particular led to the opening of Century Motorcycles on Pacific Avenue in San Pedro in 1963. Vincent had been out of business since ’55, but the shop did well selling BSAs, then Triumphs and Nortons, throughout the Brit-bike glory days of the 1960s and early ’70s, sometimes moving 100 new bikes a month out the front doors. More than a place to buy a bike or get an engine overhauled, the shop became a clubhouse for Cottom’s growing clientele. “He was a prince,” said one long-time customer, “always ready to help.”

Not that life was one smooth sail for the professional-boxer-turned-motorcycle dealer. In the 1950s, a long sickness claimed his wife, and the Korean War took his only son, Billy Gene. As therapy after these twin tragedies, Cottom poured more of himself into motorcycling, continuing to race both in organized events and impromptu street races.

“When most people would haul their bikes to the tracks in a trailer behind their cars, Wild Bill would take off for a race on his bike with nothing but a sparkplug wrench in his back pocket,” said one associate. “He was a very good, very skilled rider, the best I’d seen,” said another.

Wild Bill’s riding days came to an end in 1976, though, when he suffered a stroke. Daughter Cindy Rutherford took over operation of the dealership, but Cottom kept a desk there and was at work most days. He was also the undisputed star of the show at the Christmas and Father’s Day parties that Rutherford threw each year at Century, and that to this day remain as staples on the Southern California classic-bike calender.

There was no question, then, that the Christmas party would go on last December, even though its scheduled date came just three weeks after Cottom’s old heart gave out for good.

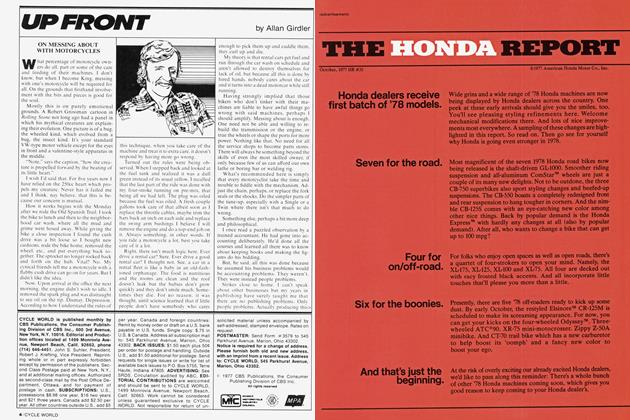

It was a grand scene that sunny Sunday. Hundreds of motorcycles lined up rear-wheel-to-curb around the shop and down the street, riders milling about, kicking tires, telling tales. Inside, two Vincents guarded Cottom’s desk. On the wall behind were framed photographs of a full, well-lived life, including one showing a smoothly muscled young man, forearms raised in the classic boxer’s pose, fists clenched, eyes full of fire. On a credenza less than an arm’s reach away, just as it had been for the last 30 years, was the folded triangle of the flag that had once draped son Billy’s casket.

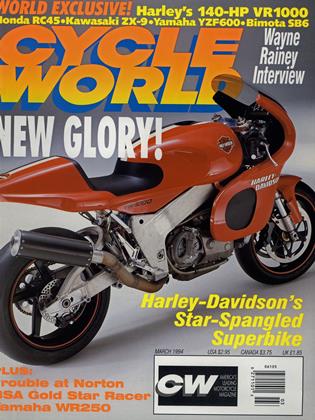

And there, at the end of room, resting on a raised platform, was Cottom’s cherished Black Lightning, all gloss-black paint and stainless steel, its sealed, gold-striped fuel tank carrying the ashes of its owner. On an easel nearby was an old black & white 8x10. It showed the same motorcycle in the 1950s, Cottom astride it wearing jackboots, dungarees and a white T-shirt, arms and chest still strong, a grin plastered across his face.

In all, some 2000 people showed up at Century Motorcycles to pay tribute to Cottom. When friends and family stood up to eulogize him, there were a few tears, but mostly smiles and rounds of applause after each speaker. At the close, someone asked for a minute of silence in Cottom’s memory. A few moments in, a big, openpipe V-Twin accelerated away from the stoplight outside the shop with a long, healthy pull through first gear, then tight, clean upshifts to second and third before fading from earshot.

It wasn’t a Vincent-more like a Harley-but, somehow, I don’t think Wild Bill minded one bit.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue