RACE WATCH

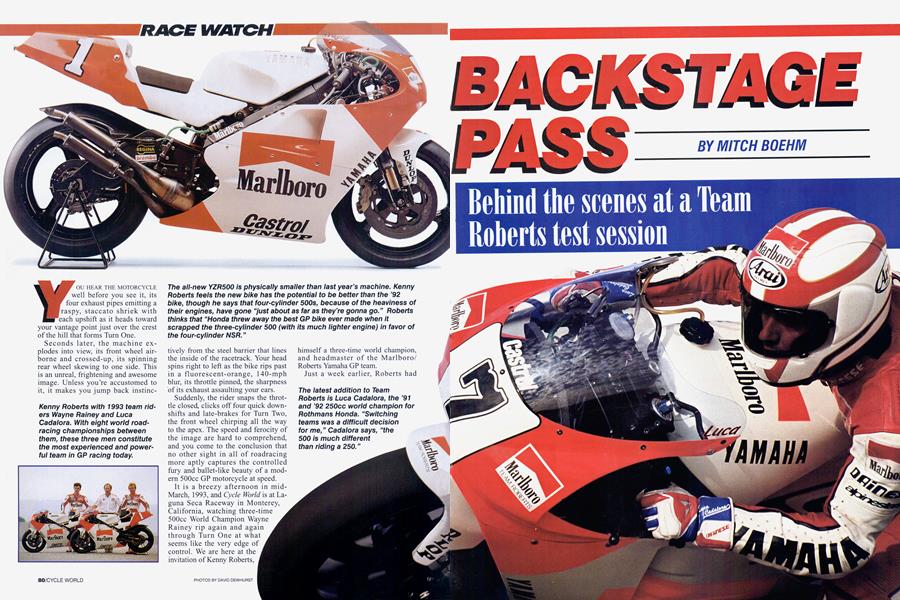

YOU HEAR THE MOTORCYCLE well before you see it, its four exhaust pipes emitting a raspy, staccato shriek with each upshift as it heads toward your vantage point just over the crest of the hill that forms Turn One.

Seconds later, the machine explodes into view, its front wheel airborne and crossed-up, its spinning rear wheel skewing to one side. This is an unreal, frightening and awesome image. Unless you’re accustomed to it, it makes you jump back instinctively from the steel barrier that lines the inside of the racetrack. Your head spins right to left as the bike rips past in a fluorescent-orange, 140-mph blur, its throttle pinned, the sharpness of its exhaust assaulting your ears.

Suddenly, the rider snaps the throttle closed, clicks off four quick downshifts and late-brakes for Turn Two, the front wheel chirping all the way to the apex. The speed and ferocity of the image are hard to comprehend, and you come to the conclusion that no other sight in all of roadracing more aptly captures the controlled fury and ballet-like beauty of a modern 500cc GP motorcycle at speed.

It is a breezy afternoon in midMarch, 1993, and Cycle World is at Laguna Seca Raceway in Monterey, California, watching three-time 500cc World Champion Wayne Rainey rip again and again through Turn One at what seems like the very edge of control. We are here at the invitation of Kenny Roberts, himself a three-time world champion, and headmaster of the Marlboro/ Roberts Yamaha GP team.

Just a week earlier, Roberts had granted Cycle World permission to attend the team’s Laguna Seca test session, the final shake-out prior to the ’93 grand prix opener in Australia in late March. This exclusive opportunity would not only give us a chance to talk to Roberts, Rainey and reigning 250cc World Champion Luca Cadalora-the newest Team Roberts member, drafted to ride 500s in place of John Kocinski, who jumped ship to pilot Suzuki’s 250 GP bike-but would also allow us to photograph the all-new and very secret YZR500, the first totally reworked 500cc GP machine from Yamaha since

BACKSTAGE PASS

Behind the scenes at a Team Roberts test session

MITCH BOEHM

the Deltabox-framed YZR bowed in 1984. Roberts’ offer would give us an insider’s view of the workings of the most competent and powerful 500cc GP team in existence.

During the week-long test, Roberts also held a press conference in which he announced details of the upcoming September 11-12 grand prix at Laguna Seca, as well as his substantial involvement in the event. For the USGP, Roberts will be more than simply a team owner; by putting a significant amount of personal capital behind this year’s race, Roberts also finds himself in the position of race promoter. Why has he involved himself so heavily in bringing the GP back to America?

“In my career,” he said during the press meeting, “the most disappointing thing was not being able to compete in a grand prix in my home country. I know what it means to these guys because I was there. I’m glad I was able to put this together.”

Roberts was equally happy with the event’s fall scheduling. “I like the September date a lot,” he said, “the weather’s better (than in April, when all other USGPs have been run). I also like it because we have a lot of time to build for the event. There are a lot of GPs before we get here; it should be more interesting for the fans.”

With the conference over and the rest of the press corps headed home, the Roberts/Marlboro team reassembled in the paddock, and within minutes the number-one and numberseven machines of Rainey and Cadalora were once again circulating Laguna’s serpentine layout, blitzing Turn One just as violently as before. >

Early reports from Europe had the new YZR500 experiencing severe teething problems during initial testing, and indicated that Rainey had complained bitterly that the bike was not nearly as good as last year’s machine. But Rainey and Cadalora were lapping quickly at Laguna on this day. While the times weren’t on record pace, Rainey’s were as quick as those he recorded during qualifying at the last running of the USGP in 1991.

“Early on in testing,” Rainey explained the following day while giving us a tour of his brand-new 4000-square-foot home that overlooks the surrounding Monterey Bay area, “we had problems with the new bike. We couldn’t get it to handle. It was frustrating, because it wasn’t even as good as last year’s bike.”

Monterey’s test sessions helped immensely. “We made a change on Monday that gave us almost a full second,” said Rainey, “and we were pumped. Now we’re going in the right direction with the chassis. We had been using traditional set-ups, things we used on last year’s machine, but they didn't work on the new bike. Now we know where we’re going. The new bike is more solid than before; you can really feel what it’s doing.”

Though it looks similar from a distance, the new YZR500 is indeed very different from last year’s model.

“The old bike was at the end of its development curve,” said Roberts, “and though we’re a little behind with the new bike, there’s more potential there. The biggest change was in chassis strength. The frame is totally different; the main beams are extruded, not a Deltabox design as before.”

Roberts wouldn’t divulge geometry differences between the ’92 and ’93 chassis, though he did say the new bike, with its sturdier frame and beefier engine cases, is roughly 15 pounds heavier than last year’s bike.

“That’s our biggest problem right now,” he said, watching Rainey drift the YZR’s rear wheel out of Laguna’s Turn 11, “making the thing lighter.”

The YZR’s two-stroke V-Four engine has also been substantially changed, though the modifications address ridability and reliability more than they increase power.

“Peak horsepower hasn’t really changed,” said Roberts, “the bike still makes roughly 180 horsepower. But with the new firing order, what you guys call a ‘Big Bang’ engine, it’s easier to ride.” >

Halfway through the 1992 season, Yamaha went to a closely spaced fir ing order for its engines in an attempt to run with the dominant Hondas, which had initiated Big Bang technol ogy at the start of the season. The change boosted the YZR's ridability, and Rainey won races on the bike, but the firing order put much more stress on internal engine components, espe cially gearboxes and engine cases. En gine vibration was intense.

"The entire engine is stronger to handle the extra stress and vibration," said Rainey. "The cases are alu minum, not magnesium, and the transmission is stronger, as well."

Another technological advantage the Roberts team plans to put to good use in 1993 are the computerized en gineand suspension-management systems developed during last year and now fully integrated into the new YZRs. Engine-management systems have been in use for a few years now, though it is in the area of electronic suspension management that Roberts claims the most significant gains have been realized.

For race technicians, determining a machine's ideal suspension and engine settings has always been headache-inducing work. Expecting a> rider to accurately analyze what’s going on beneath him, return to the pits with meaningful information and do it all while riding near the limit is a tall order. Few riders are that good at development.

The system employed by the Roberts team comprises a complex computer/sensor set-up formulated by the team’s Development Coordinator Warren Willing, an ex-racer himself. The system basically works like this: Sensors connected to the engine, fork and shock measure frontand rearsuspension travel, suspension loads, engine rpm, throttle position, wheel speeds and a host of other variables. Digital data from these sensors is stored in an on-board data-loggerabout the size of a paperback bookwhich can hold information for up to four laps.

When a rider pits during a test session, a technician removes the data card and downloads it into a computer. The information is then displayed on a computer screen, which allows technicians to determine if the changes made are doing what they were designed to do: produce quicker lap times.

If Cadalora, for instance, feels the front end is bottoming while braking for a specific corner, technicians can check the data to confirm or deny it. If the gearing of Rainey’s machine is altered to help it accelerate between corners, again, the data can confirm or deny it regardless of what Rainey’s seat-of-the-pants feeling tells him. If > the rider is unhappy with the bike’s handling, the crew can make changes designed to combat the problem and then check the results when the rider pits four laps later.

Another area of this computerized sophistication is the YZR500’s electronically controlled Öhlins shock. The unit is, of course, fully adjustable, but what makes it so special is its programmability. Öhlins technicians, using suspension data gathered at a specific racetrack, can formulate up to six separate sets of preprogrammed damping instructions for the shock. Two of these damping maps can be integrated during a race or practice session, an A/B switch on the right handlebar giving the rider a damping choice in mid-flight.

When might a rider change settings mid-race? Possibly to compensate for tire wear, heat, changing track conditions or, as Roberts puts it, “if we’re going backwards.”

According to one technician, Team Roberts is the only team now using the Öhlins-based programmable system. “Electronic suspension has made a big difference for us,” Roberts said. “It’s really helped us this year with the new bike. It backs up rider feedback, and allows us to be more productive with our limited testing time. Chasing the wrong setting all day long isn’t productive.”

Tires also play a major part in a GP bike’s set-up, and for ’93 the Roberts camp has switched from the Michelins it used in ’92 to Dunlops. The move makes Rainey a happy man.

“The Dunlops are more forgiving,” he said, “last year’s Michelins stuck well enough, but when they let go, they let go in a hurry.”

Rainey ended up on his head a lot during the roller-coaster-like ’92 season, though he realizes the crashes were due to more than just unforgiving tires. Pre-season injuries and selfinduced pressure played a big part.

“I wasn’t 100 percent going in last year,” Rainey said, “my leg was pretty weak. I also felt I had to equal what Kenny did (win three world 500cc championships). All last year, I felt like I was riding over my head. The bike threw me down a lot.”

Rainey’s third 500cc title is now behind him, and though the prospect of a fourth championship looms, Rainey has the relaxed, confident manner of a man at the top of his game mentally and physically.

“I’m in pretty good shape right now,” Rainey said as he walked us through his just-finished weight room adjacent to the massive, three-car garage. “I ride the stationary bike every day, I’ve increased my strength with weights, and my bad leg is almost as strong as my good leg. I’ve got to work harder than the younger guys,” he added with a grin, “but I sure enjoy beating ’em.”

Rainey's toughest competition for this year's title will undoubtedly come from Rothmans Honda ace and 1992 500cc runner-up Michael Doohan, though, just as Rainey did last year, Doohan will begin the sea son hurt, the result of a practice crash that broke a small, non-weight-bear ing bone in his wrist. Doohan will re portedly compete at the Eastern Creek, Australia, opener, though it's doubtful he'll be 100 percent.

That may give Rainey an advantage early-on, though the 3 3-year-old threetime champ isn’t taking anything for granted. With the dramatic turnaround of last year’s title chase still fresh in his mind, Rainey knows firsthand the adage “It’s not over until it’s over.”

Roberts, too, understands the topsy-turvy nature of the GP trade, though the confidence he has in his number-one rider is considerable.

“Wayne’s gonna be there,” he says, “no matter what.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontExit the Ogre

June 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsGetting There

June 1993 By Peter Egan -

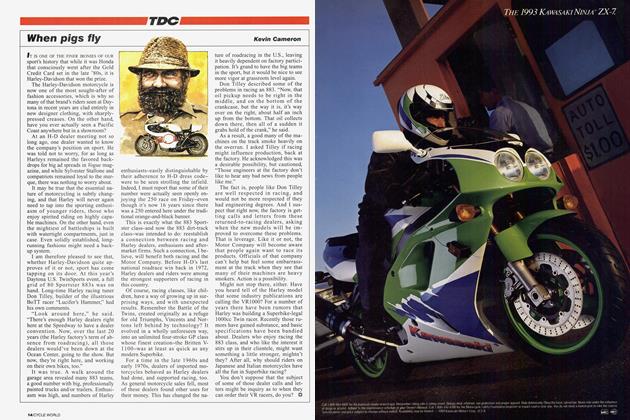

When Pigs Fly

June 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupMz Set To Invade United States

June 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupJapan's Retro-Racer Revival Continues

June 1993 By Pat Devereux