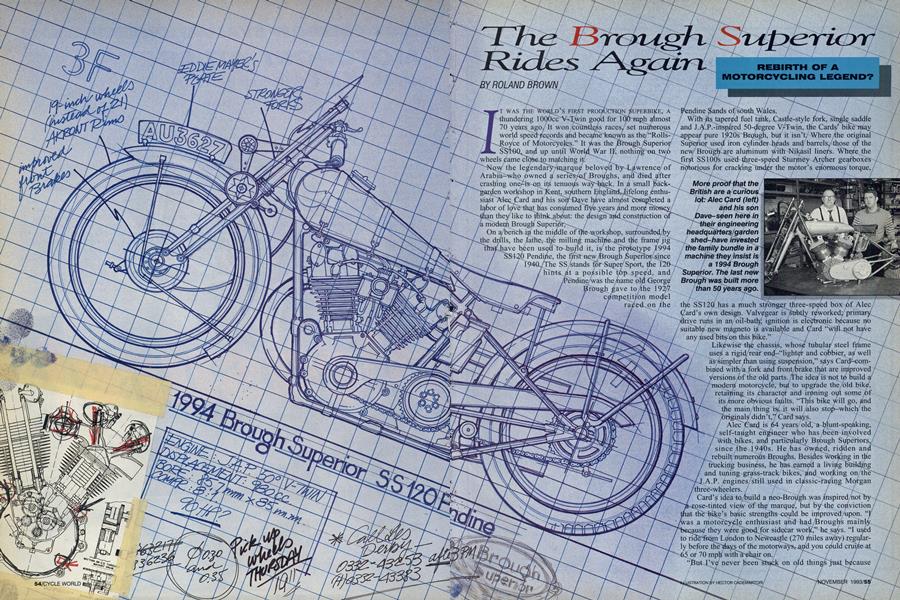

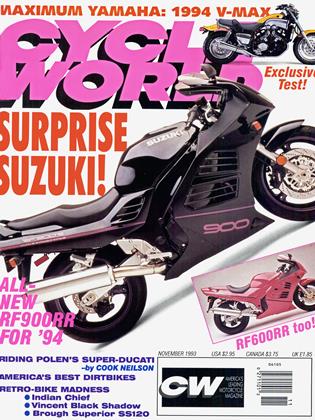

The Brough Superior Rides Again

REBIRTH OF A MOTORCYCLING LEGEND?

ROLAND BROWN

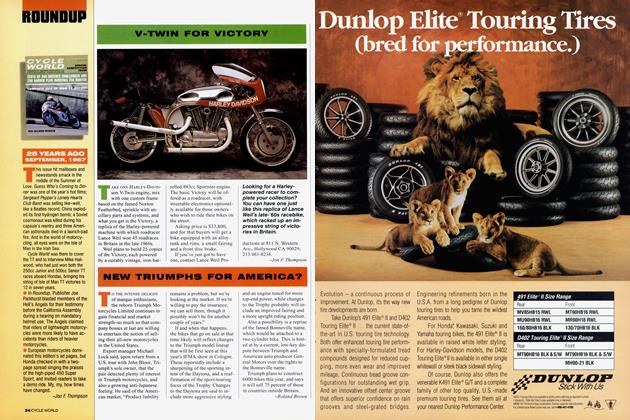

IT WAS THE WORLD'S FIRST PRODUCTION SUPERBIKE, A thundering 1000cc V-Twin good for 100 mph almost 70 years ago. It won countless races, set numerous world speed records and became known as the "Rolls-Royce of Motorcycles." It was the Brough Superior SS100, and up until World War II, nothing on two wheels came close to matching it.

oy Lawrence of ., and died after In a small back-, d,-.lifelong enthusiast Alec Card and his sop Dave hâve almost completed a labor of love that has consumed five years and more rrioneW '""than they like to think about: the design and construction of a modern Brough Superior.:-^ ""P On a bench in the middle of the workshop, surrounded by the drills, the lathe, the milling machine and the frame jig that have been used to build it, is the prototype 1994 / SSI20 Pendine, the first new Brough Superior since j 1940. The SS stands for Super Sport, the 120 Nw/ j j hints at a possible tóp speed, and / Pendine was the name old George ƒ / / Brough gave to the 1927 / competition model ^'7 J raced on the

Pendine~ands of south Wales.

With its tapered fuel tank, Castle-style fork, single saddle and J.A.P.-inspired 50-degree V-Twin, the Cards’ bike may appear pure 1920s Brough, but it isn’t. Where the original Superior used iron cylinder heads and barrels, those of the new Brough are aluminum with Nikasil liners. Where the first SSlOOs used three-speed Sturmey Archer gearboxes notorious for cracking under the motor’s enormous torque,

the SSI20 has a much stronger three-speed box of Alec Card’s own design. Valvegear is sttbfly reworked; primary drive runs in an oil-bath; ignition is electronic because no suitable new magneto is available and Card “will not have anY used bits on this bike.” /

Likewise the chassis, whose tubular steel frame uses a rigid rear end-“lighter and cohbier, as well as simpler than using suspension,” says Card-combined with a fork and front brake that are improved versions of the old parts. The idea is not to build a modern motorcycle, but to upgrade the old bike, / retaining its character and ironing out some Of its more obvious faults. “This bike will go, and Y/'‘s*-\ the main thing is, it will also stop-which the originals didn’t,” Card says.

j Alec Card is 64 years old, a blunt-speaking, /1*^/ self-taught engineer who has been involved I 7 with bikes, and particularly Brough Superiors, / since the 1940s. He has owned, ridden and rebuilt numerous Broughs. Besides working in the f trucking business, he has earned a living building ƒ anc* tuning grass-track bikes, and working on the 7 J-A.P. engines still used in classic-racing Morgan /three-wheelers. i

/ Card’s idea to build a neo-Brough was inspired not by pa nose-tinted view of the marque, but by the conviction pat the bike’s basic strengths could be improved upon. “F /was a motorcycle enthusiast and had Broughs mainly /because they were good for sidecar work,” he says. “I used to ride'ftom London to NeWeasJle (270 miles away) regularly before theriaysof the motorways?-and you could cruise at 65 or 70 mph with Tehair on,

“But I’ve never been on old things just because they’re old. I’ve always considered I could make the thing the same but better. That’s why we had to build new, stronger forks, because with the forks they used, you couldn’t put a decent brake on it. What’s the point in me sitting on a bloody old bike frightened to do more than 50 mph because I can’t stop?”

Unlike George Brough, who bought-in all the SS 100’s major components except the frame and assembled them at his workshop in Nottingham, the Cards had no choice but to make virtually all their bike. The engine can be called a J.A.P., Alec Card says, because he owns that name.

“Villiers took over J.A.P. in the ’50s but never registered the name. We got lawyers to do searches, to make sure nobody had used it for a certain time, and raised it again,” he explains.

“We’ve acquired the rights to use the name Brough Superior from the person who owns it-I can’t say who that is, but it’s not in the Brough family now. I’ve got a contract with them that says I can use the name until the day I die, so what you’re looking at is a genuine Brough Superior SSI20 Pendine.”

Thousands of hours and tens of thousands of dollars have gone into its construction. “For all these components we’ve had to start from nothing and make wooden patterns,” says Card, holding the carved shape of a considerably heftier-thanstandard steering head. He adds, “The engine was designed with the aid of a lot of friends in the motor industry.”

Basic layout is similar to the original, with this motor’s 85.7 x 85mm bore and stroke giving a capacity of 980cc. “But you can go to 1275cc or even 1300cc if you want to,” Card says. “The last pre-War J.A.P. engines were 75 horse-

power, and the alloy racing engines they did in the Fifties were 90 horse. I think this would produce about that.

“And we’ve uprated it so much in the construction. The crankcases are three times as strong. We’ve copied the old original rocker geometry but slightly altered the valve angle. The exposed valve springs work okay, provided you don’t mind a dirty kneecap from the oil,” Card laughs. The SSI20 has 8:1 compression to run on modem fuel. Carburetor will be an Amal Concentric; the upswept exhausts will be made by a specialist in south London. Gearchange will be by a hand lever on the right of the fuel tank.

The chassis, too, is Card’s own design, closely based on the original. The forks, which he calls “Carmac,” are stronger versions of Brough’s old Castle units, which were based on a Harley-Davidson design. The iron, 8-inch front drum brake will be much more powerful than the feeble original. Instead of the 21-inch wheels of early Broughs, this bike’s Akront alloy rims will be in 19-inch front, 18-inch rear diameters to allow fitment of modem tires.

The new Pendine, like the original, will be sold as a competition bike with no lights or speedo. It would be up to an owner to add those if needed, and to get the bike road-registered-although Card insists that should not be a problem. His main concern is whether with funds running very low, he can get some orders-along with deposits-that would allow him to finish the prototype, produce a handful of bikes and begin to recoup some of his investment.

“I’ve often wished I’d never started it, because I'd be a lot wealthier now, rather than up the chute,” he says. “I never realized it would take so long or cost so much. Now we’re desperately trying to get the bike finished so we can try to get some money back in. We’ll have to sell them for £30,000 (about $45,000), roughly what an original Brough is worth, because that’s what they'll cost us to make. I just hope there’s a market for them at that price.”

Despite the cost, there surely will be takers for the uniquely idiosyncratic SS120, which, although neither a genuine classic nor a truly modern machine, promises to combine vintage character with usable, new-bike

performance. And if Card has doubts about the project, he doesn’t let them get him down for long. “Look at that bloody thing!” he says, jabbing a finger at an old black-and-white photo of a well-used Brough at speed. “Looks like an old mangle, doesn’t it, but nothing could touch them. They were beating the Bentleys over the flying kilometer.

“What has really created this bike is enthusiasm,” he goes on. “George Brough and the people around him were innovators. They ate, drank and slept motorbikes. And I’ve got an idea that this is roughly what they would hqve made today. I just can’t wait to ride it.” ^

View Full Issue

View Full Issue