Evergreen

TDC

Kevin Cameron

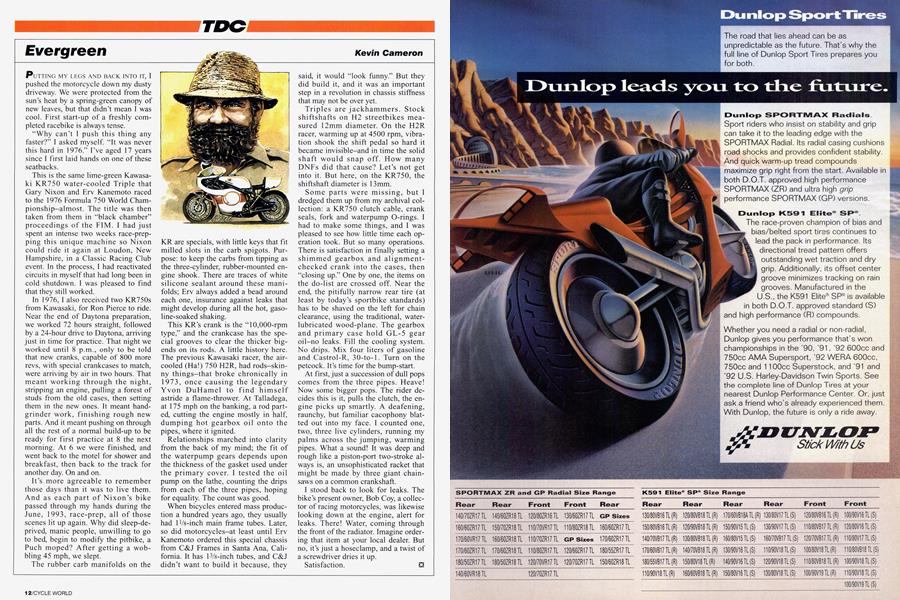

PUTTING MY LEGS AND BACK INTO IT, I pushed the motorcycle down my dusty driveway. We were protected from the sun’s heat by a spring-green canopy of new leaves, but that didn’t mean I was cool. First start-up of a freshly completed racebike is always tense.

“Why can’t I push this thing any faster?” I asked myself. “It was never this hard in 1976.” I’ve aged 17 years since I first laid hands on one of these seatbacks.

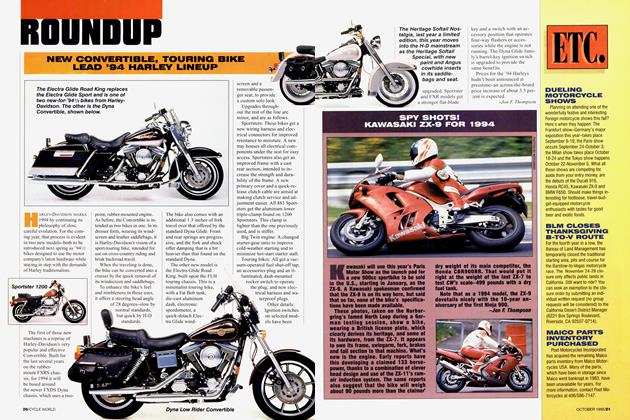

This is the same lime-green Kawasaki KR750 water-cooled Triple that Gary Nixon and Erv Kanemoto raced to the 1976 Formula 750 World Championship-almost. The title was then taken from them in “black chamber” proceedings of the FIM. I had just spent an intense two weeks race-prepping this unique machine so Nixon could ride it again at Loudon, New Hampshire, in a Classic Racing Club event. In the process, I had reactivated circuits in myself that had long been in cold shutdown. I was pleased to find that they still worked.

In 1976, I also received two KR750s from Kawasaki, for Ron Pierce to ride. Near the end of Daytona preparation, we worked 72 hours straight, followed by a 24-hour drive to Daytona, arriving just in time for practice. That night we worked until 8 p.m., only to be told that new cranks, capable of 800 more revs, with special crankcases to match, were arriving by air in two hours. That meant working through the night, stripping an engine, pulling a forest of studs from the old cases, then setting them in the new ones. It meant handgrinder work, finishing rough new parts. And it meant pushing on through all the rest of a normal build-up to be ready for first practice at 8 the next morning. At 6 we were finished, and went back to the motel for shower and breakfast, then back to the track for another day. On and on.

It’s more agreeable to remember those days than it was to live them. And as each part of Nixon’s bike passed through my hands during the June, 1993, race-prep, all of those scenes lit up again. Why did sleep-deprived, manic people, unwilling to go to bed, begin to modify the pitbike, a Puch moped? After getting a wobbling 45 mph, we slept.

The rubber carb manifolds on the KR are specials, with little keys that fit milled slots in the carb spigots. Purpose: to keep the carbs from tipping as the three-cylinder, rubber-mounted engine shook. There are traces of white silicone sealant around these manifolds; Erv always added a bead around each one, insurance against leaks that might develop during all the hot, gasoline-soaked shaking.

This KR’s crank is the “10,000-rpm type,” and the crankcase has the special grooves to clear the thicker bigends on its rods. A little history here. The previous Kawasaki racer, the aircooled (Ha!) 750 H2R, had rods-skinny things-that broke chronically in 1973, once causing the legendary Yvon DuHamel to find himself astride a flame-thrower. At Talladega, at 175 mph on the banking, a rod parted, cutting the engine mostly in half, dumping hot gearbox oil onto the pipes, where it ignited.

Relationships marched into clarity from the back of my mind; the fit of the waterpump gears depends upon the thickness of the gasket used under the primary cover. I tested the oil pump on the lathe, counting the drips from each of the three pipes, hoping for equality. The count was good.

When bicycles entered mass production a hundred years ago, they usually had H/8-inch main frame tubes. Later, so did motorcycles-at least until Erv Kanemoto ordered this special chassis from C&J Frames in Santa Ana, California. It has l3/8-inch tubes, and C&J didn’t want to build it because, they said, it would “look funny.” But they did build it, and it was an important step in a revolution in chassis stiffness that may not be over yet.

Triples are jackhammers. Stock shiftshafts on H2 streetbikes measured 12mm diameter. On the H2R racer, warming up at 4500 rpm, vibration shook the shift pedal so hard it became invisible-and in time the solid shaft would snap off. How many DNFs did that cause? Let’s not get into it. But here, on the KR750, the shiftshaft diameter is 13mm.

Some parts were missing, but I dredged them up from my archival collection: a KR750 clutch cable, crank seals, fork and waterpump O-rings. I had to make some things, and I was pleased to see how little time each operation took. But so many operations. There is satisfaction in finally setting a shimmed gearbox and alignmentchecked crank into the cases, then “closing up.” One by one, the items on the do-list are crossed off. Near the end, the pitifully narrow rear tire (at least by today’s sportbike standards) has to be shaved on the left for chain clearance, using the traditional, waterlubricated wood-plane. The gearbox and primary case hold GL-5 gear oil-no leaks. Fill the cooling system. No drips. Mix four liters of gasoline and Castrol-R, 30-to-l. Turn on the petcock. It’s time for the bump-start.

At first, just a succession of dull pops comes from the three pipes. Heave! Now some bigger pops. The rider decides this is it, pulls the clutch, the engine picks up smartly. A deafening, raunchy, but familiar cacophony blatted out into my face. I counted one, two, three live cylinders, running my palms across the jumping, warming pipes. What a sound! It was deep and rough like a piston-port two-stroke always is, an unsophisticated racket that might be made by three giant chainsaws on a common crankshaft.

I stood back to look for leaks. The bike’s present owner, Bob Coy, a collector of racing motorcycles, was likewise looking down at the engine, alert for leaks. There! Water, coming through the front of the radiator. Imagine ordering that item at your local dealer. But no, it’s just a hoseclamp, and a twist of a screwdriver dries it up. Satisfaction.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue