REFLECTIONS ON A SEASON

Notes from the final AMA roadrace national

RACE WATCH

KEVIN CAMERON

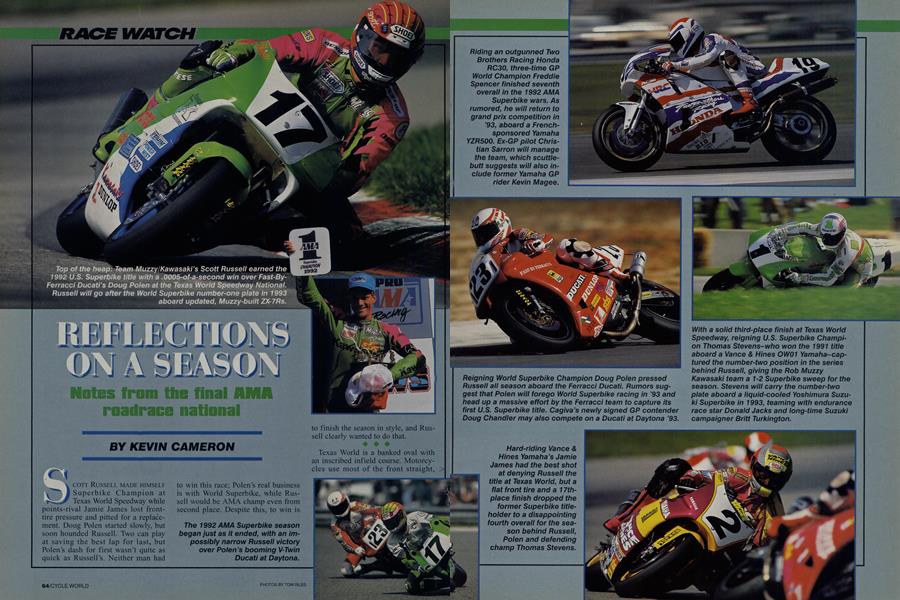

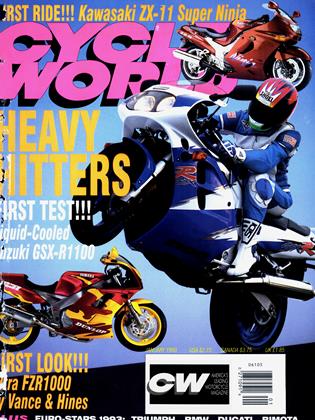

COTT RUSSELL MADE HIMSELF Superbike Champion at Texas World Speedway while

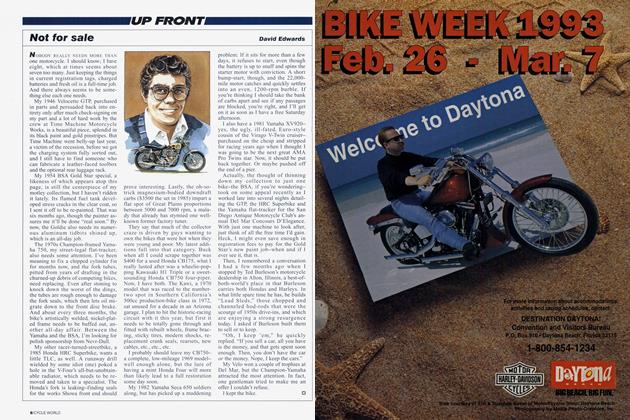

points-rival Jamie James lost fronttire pressure and pitted for a replacement. Doug Polen started slowly, but soon hounded Russell. Two can play at saving the best lap for last, but Polen’s dash for first wasn’t quite as quick as Russell’s. Neither man had

to win this race; Polen’s real business is with World Superbike, while Russell would be AMA champ even from second place. Despite this, to win is to finish the season in style, and Russell clearly wanted to do that. Texas World is a banked oval with an inscribed infield course. Motorcycles use most of the front straight, enter the Turn One bowl, then hook around into a short infield straight, followed by a tightly connected series of slow turns that returns to the frontbowl straight. A lap is 1.8 miles, and a good Superbike time is a 1:07. The straight is fast-close to 160 mph-but most of the infield is lower-gear acceleration, turning and braking. Lowspeed acceleration unloads front wheels, making them push, and the Texas pavement, coated with dried clay, made the push worse. Everyone was looking for grip.

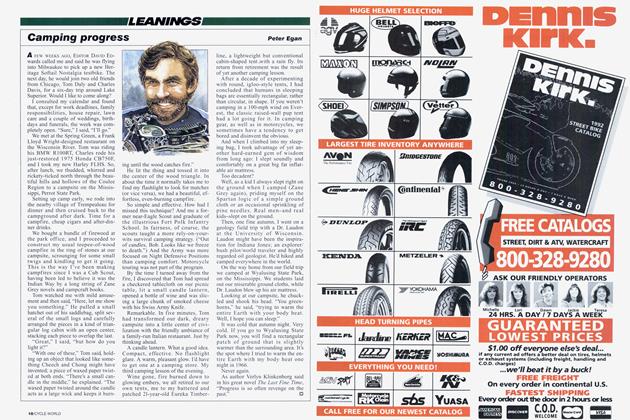

The qualities of Russell’s Kawasaki were broad enough to cover the conditions in Texas. It had won at both Daytona and Loudon, and proved it could handle fast corners and slow. Polen’s Ferracci Ducati might have done better on a more open circuit, but the section before the Texas finish straight is very tight. James’ Yamaha had displayed new-found chassis qualities at Loudon, but on the slippery Texas surface, he reckoned he was a day’s practice behind the others.

Dunlop’s tire technician, Jim Allen, likened track conditions to those at Memphis a few years ago, when either the softest or the hardest compounds would work-but nothing in between. Middle-range compounds were being cut by the track as the tires slid without gripping.

Texas shares with Brainerd, Minnesota, the distinction of having an impressive sixth-gear approach to Turn One. Riders held their throttles on far down the bowl as they dove from the top lane, making an observer feel as if under air attack. The inline-Fours wind up to impossible pitch, the Muzzy Kawasakis highest of all-beyond 14,000-making the listener’s vocal cords painfully tight in sympathy. The Yamahas may not reach quite as high, but have a flutier, richer sound. At their final upshift you hear engine rpm bounce for an instant as the crank’s mass hits the driveline. Breathing through all this shrieking, the Ducati is a heavy bumblebee, a sound more felt than heard.

Braking from high speed calls back-torque limiters into action. These devices are built into clutches to prevent engine braking on closed throttle from dragging or hopping rear wheels during hard deceleration. Lack of this technology-now commonplace-was a major reason why MV Agusta fell behind the twostrokes in mid-1970s GP racing. The need arose when the coming of softcompound slick tires made it possible to brake with close to zero weight on the rear tire.

Kawasaki uses a ramp-actuated device that lifts the clutch pressure plate in proportion to any reverse torque. Therefore, instead of the whee-wheewhee of quick, high-rpm downshifts, you hear very little from the engines, which are lagging and almost inaudible. The Vance & Hines Yamahas use a similar device. The steely clash of released metal clutch plates could be heard during their Turn One entries. Few riders want to add downshifting to their already full workload during the ticklish business of high-speed braking and turning on the uncertain surface.

On the Honda RC30, all plates transmit forward torque, but when the wheel drives the engine, it drives through only a fraction of the plates-which slip. Freddie Spencer was rapping out three quick downshifts after braking on his Two Brothers Honda, but Tom Kipp on the Commonwealth Honda was actually pulling in the clutch, letting his engine idle as he braked. The Ducatis have no limiters. Ferracci simply sets the idle up to reduce engine braking. Another useful technique is a finger on the clutch, two-stroke style; when the rear wheel hops or skids, even a slight pressure banishes the symptoms.

Currently being widely tested in GP racing is Eraldo Ferracci’s shift switch, claimed by some to save as much as a second a lap. As the shifter mechanism engages the drum, a switch closes, activating a small delay box containing a timing circuit that cuts the ignition for .06 of a second. This releases engine pressure on the gear-engaging dogs just long enough to complete an upshift. The device is inactive on downshifts.

Yoshimura is ignoring Superbike until the new liquid-cooled GSXR750 arrives for 1993, running just the chubby but promising supersport GSX-R600 now. The team hopes that concepts it has developed in the last two years will pay off once combined with the new engine. This includes a sealed ram-airbox intake system.

The Ducatis have used such an airbox for three years now, drawing air through vertical slots on either side of the front numberplate into a twoarmed carbon-fiber airbox that surrounds the intake trumpets. At the Suzuka 8-Hour, Kawasaki used a similar system, but fed by a single, offcenter intake big enough to swollow your whole arm. The fairings on the Team Muzzy bikes have these intakes, but they are blanked-off, and Muzzy doesn’t discuss the whys of the system he uses instead. His system takes in air centrally, above the radiator, to feed a truly immense airbox whose roof is the tank itself.

Ray Plumb, who manages gracefully to serve both the Commonwealth Team and Honda, displayed a beautifully executed replica of the intake system seen on HRC bikes at Suzuka. It employs NACA ducts at either side of the front number plate, feeding a giant box that replaces the front quarter of the fuel tank. This serves the downdraft carb cluster atop the VFour engine. Reportedly, there is a top-speed gain (measured at Honda’s chosen desert road), enough to suggest that the box works more by excluding hot air than by boosting pressure through ram compression. The temperature drop is about 20 degrees F-well worth having.

Honda’s disinclination to hand over its latest technology to potential competitors (the U.S. Commonwealth Team, for example) is well-known, and the 1992 season result is desperation on the starting grid. Where is Kawasaki/Ducati-beating technology to come from? The new RC50 remains within the womb of HRC, despite intense rumor activity. Men of enterprise and experience-like Ray Plumb-might just stop waiting for better things to come in boxes, and ignore the no-development-outsidethe-factory policy. Or look at it another way; what if the airbox is not a replica? What if it’s all a corporate “cover” for the U.S. reappearance of serious Honda factory engineering? Interestingly enough, Heavy Dudes straight from Japan, wearing HRC shirts, were infesting the Commonwealth pits. Surely they didn’t come all this way just to disapprove?

Suzuki may take a greater hand in U.S. racing in 1993, rather than leave matters strictly to Yoshimura as in the past. Having become sportbike sales kings through the attractive pricing that came with its clever modular 600/750/1 100 engine system, the company would like to make certain of its 1993 return to competitiveness. Money and direct factory connection will help, provided the company does not try to win races by remote control, as it did with notable lack of success 20 years ago.

Eraldo Ferracci does not encourage the rumors circulating elsewhere regarding possible bore/stroke changes from Ducati. These suggest the goal would be increased combustion efficiency resulting from a slightly longer stroke and smaller bore. Detail > engineering has fought the spark lead down from the original long 45 degrees BTDC at peak torque down to just under 40, which is progress, but still short of the quick, efficient 27 degrees of the 25-year-old Cosworth DFV FI engine. Also, Ducati’s 40-degree valve-included angle is large for the current era.

The Yamaha has had several fine performances this season, but clearly needs a new cylinder head. The current head requires much longer spark lead than do the four-valve heads on Kawasakis and Hondas. The combustion space in any high-compression, short-stroke engine is pretty much confined to the region defined by the valves, with all the real estate outside that employed as tight squish ( 12-15 percent of the bore area). If the valves are big and widely spaced, the chamber becomes wider and, to retain a desirably small compression volume, thinner. Having given life to the fivevalve idea, the company doesn’t want to do the obvious thing and revert to the simpler four-valve chamber that its rivals use to whack them. Therefore, the Department of Rumor and Leak indicates that the new headpossibly developed for Suzukawill have five smaller valves, set in a tighter cluster. This was exactly the difference between Alfa’s unsuccessful flat-Twelve and Ferrari’s winning 312T a few years ago. Alfa filled the chamber with giant valves, while Ferrari used dinky ones in a tight group. Don’t automatically associate small valves with lower performance. Higher intake velocity can translate to improved combustion speed, something the Yamahas need.

Supersport racing is in a tightlipped state because rules interpretation permits replacement of stock valve-seat inserts with taller ones that raise compression by pushing the valves into the chamber. This is a $2000 mod. As a result, the Texas 600 Supersport race was three events in one. First, the Honda factory class, with two machines cruising nose-totail (Kipp and Smith), then the Suzuki factory class (two bikes also, Sadowski and Turkington) some distance back, and finally, the cut-andthrust cluster of actual 600 supersport machines. Tom Kipp won overall, with Randy Renfrow earning special distinction by projecting himself towards the Suzukis to finish fifth.

Southwest Motorsports claimed first and second in the 250 championship, with Colin Edwards, Jr. and Chris D’Aluisio finishing first and third at Texas on Dave Harold-prepared Yamahas. Jim Filice on an underdog Honda challenged for the lead, but was knocked out of contention by traffic to finish 9 seconds back. The ’93 Honda RS250 is reported to be a replica of this year’s redesigned GP NSR, but rumor has it that no U.S. rider or team has as yet ordered one. And what about Aprilia? Although its factory machines are very fast in GPs-able on occasion to beat the reigning NSRs-and its kitted production machines are also fast, the current production machine is not a match for the better private Yamaha TZs. This could easily change, for small companies are fast on their feet.

If all goes as planned, the Texas SuperTwins event was the AMA’s last ever. Formerly diverse, fascinating and full of clever homebuilts, the class has lately provided little more than exercise for the Ducati fleet. Where were Moto Guzzi, HarleyDavidson or other potential Twins producers, when we needed them?

A bigger schedule of 12 or more races is planned for 1993, beginning at Phoenix, then moving on to Daytona. This, reportedly, is the result of nudging from the factory teams, who had considered extending their operations to the WERA series if more events were not forthcoming. For many years, it has been acknowledged that roadracing cannot grow in the U.S. without TV. So far, it has come in fits and starts: good treatment at the Laguna GP, more at Miami, but without solid, season-long major-sponsor coverage. Is it out there in the near future somewhere, rushing at us?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue