SERVICE

Joe Minton

Slide for life

In October of 1991, I bought a used Kawasaki ZX-10 with just over 7000 miles on it. The previous owner had maintained it fairly well. When riding it earlier this year, I lightly touched the rear brake pedal and the next thing I knew, the rear wheel was locked up at 65 mph. The nut on the rear-brake torque-link bolt had fallen off, allowing the caliper to rotate around and jam into the swingarm, locking the rear wheel. Have you ever heard of this happening? I replaced the nut and bolt, then drilled and pinned the bolt. I can’t believe the factory doesn’t do the same thing. I’d had new tires installed less than 1000 miles before the incident, but the dealer who did the work says it was my fault for not checking all nuts and bolts before each ride.

Lamar M. Shafer West Hazelton, Pennsylvania

Not only has this happened before, but it happened to me! In my case, the bike had a cotter pin through the bolt, but the cotter pin broke and there apparently was insufficient torque on the nut to keep it from working loose and falling off

Kawasaki specifies a normal 8mm bolt and a self-locking nut at the caliper end of the brake torque arm; the swingarm end calls for a shouldered bolt that’s drilled and fitted with a castle nut secured by a cotter pin. Both nuts should be torqued to 18 foot-pounds, and I recommend a drop of blue Loctite on the threads of both-just to be sure. If your ZX-10 did not have this exact nut-and-bolt arrangement, somebody changed it.

It’s not necessary to remove the torque arm when replacing the rear tire, so your dealer might not be the culprit. Still, a good shop will inspect torque arms and other critical components anv time they sendee affiliated mechanisms. The statement your dealer made to you is unrealistic and little more than a copout intended to protect him in the event of a lawsuit. Certainly, all riders should inspect their motorcycles regularly, but no one can be expected to check every> nut and bolt before each ride. That’s why Kawasaki put a self-locking nut on one end of the torque arm and a cotterpinned nut at the other.

Win one, lose one

I just finished reading your March, 1992, issue and, as usual, was happy with most of it. However, you made a couple of statements that 1 disagree with.

First, as a graduate of one of the country’s best motorcycle mechanics schools, I was trained to finish a cylinder bore with a 45-degree crosshatch to aid in oil retention, ring sealing and better break-in. I’ve rebuilt engines using this technique and have achieved excellent results in compression and leak-down tests, and in performance. But you said that Jesse Gatlin had given the cylinders in his Suzuki GSX-R1186 project dragbike a supersmooth finish. That contradicts everything I’ve learned from teachers who have been around the motorcycle and machining businesses a long time.

Also, you state that winterizing a bike should include draining the gas tank. Well, that’s the best way to allow a tank to rust over the winter in the snow belt-or anywhere, for that matter. Instead, the tank should be filled to the brim and a fuel stabilizer added. That way, the inside of the tank will stay shiny for a long time.

Jose Obando Phoenix, Arizona

When I first started working as an apprentice bike mechanic around 1962, it was standard procedure to use a rough (280 grit or so) hone and establish the 45-degree angle you describe between the “in ” and the “out’’ hone marks. This left somewhat of a file-like surface on the bore that allowed new piston rings to machine themselves into a proper fit by scraping up and down on the hone marks until they mated perfectly to the cylinder walls. Obviously, the more accurately the rings and cylinder fit together in the first place, the less the need for the honed finish to be rather rough.

But that was 30 years ago. About 20 years ago, Honda-which has a reputation for building engines that have excellent ring-sealing properties-began putting a much smoother finish on its production cylinders; the other manufacturers soon followed suit. And if you could be present at the post-race teardowns at major drag races and roadraces, you d see a lot of very smooth, very shiny cylinder walls.

Over the past couple of decades, cylinder-honing practices have changed, and for good reasons. For one, the sophistication of modern boring equipment has made the task of machining truly round and straight cylinders much easier than ever. So, too, have advances in piston-ring manufacturing made possible the production of much more accurate rings. As a result, piston rings and cylinder bores in new or rebuilt engines mate much more precisely than in decades past. This allows a quick break-in period without the need for the coarse, 45-degree crosshatch you were taught to leave on the cylinder walls.

In fact, those same manufacturing advances have also allowed the development and use of harder and/or more wear-resistant materials in piston rings and cylinder bores. Were these improved materials used in the poorerfitting rings and bores of the past, the break-in process would take forever, even with a coarsely honed finish on the cylinder walls.

On the other hand, you are correct in your criticism of my recommendation to fill a gas tank for winter storage rather than drain it. I forgot that here in Southern California we don’t have as much trouble with moisture as someone might in, say, Minnesota or Seattle. And you, in exceptionally dry Phoenix, should have even less trouble. The basis for my advice was the knowledge that we have more problems with the gasoline itself when storing bikes here in our dry climate. Small amounts of gasoline often tend to seep past the fuel valve and into the carbs, where it then deteriorates and clogs the jets and other fuel passages if the bike sits unused for a long time. So, around here, the threat is more from gummed-up carbs than from rusty tanks. But for people in most parts of the country, fuel preservatives will retard deterioration over a winter, just as you suggest. A tankful of fresh aviation gasoline is probably the best choice for winter storage because avgas is very stable.

Every bike I’ve owned for the past 20 years has had the interior of its gas tank coated with a sealant. As far as I know, only BMW and Harley-Davidson do this for their customers. With other bikes, we either have to take preventive (and easily forgotten) measures at storage time or coat the tanks ourselves. For the latter, I highly recommend the Kreem sealant kit. Your correction on this matter was in order; thanks for the kick in the slats.

Planetary paradox

I have a 1981 Yamaha Virago 750 that has a problem with the electric starter and its mechanism. When I try to start the engine, the starter gears do not seem to mesh, making a grinding noise. When they do mesh, the starter often disengages before the engine starts, perhaps because of the high compression of the big Twin. Is there a cure for this problem?

Tommy Thomison Ada, Oklahoma

Indeed, the problem you describe is a common one caused by a fault in the design of the planetary gear unit built onto the end of your Yamaha s starter motor. A plate in the gearbox must resist rotation against the full torque of the starter motor; but that plate is not keyed in place and is held only by friction. Often, the plate will turn when the starter is engaged, and when that happens, little or no torque is delivered to the output shaft of the starter motor assembly.

The remedy is to weld the plate to the ring gear. This must be done by filing matching notches in the two parts, welding them together at the notches, then dressing the welds so the assembly will slip back into the starter body. You can have this procedure done, along with an overhaul of the entire starter, by Christman !'s, (11650 Hart St., North Hollywood, CA 91605; 818/768-3673) on an exchange basis for $125. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

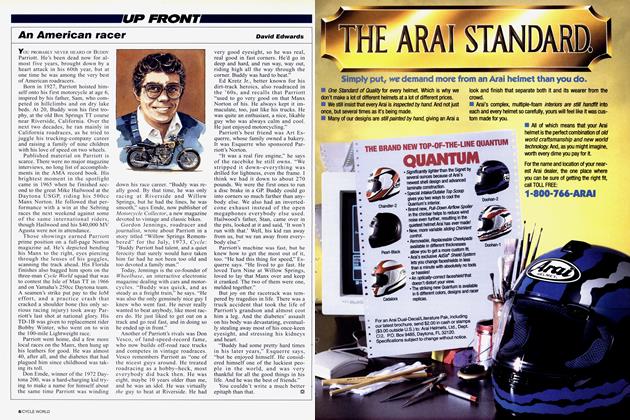

Up FrontAn American Racer

September 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsElectra-Glide

September 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCOily Harry

September 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1992 -

Roundup

RoundupNorton's Future Assured, Maybe

September 1992 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupShoei Reorganizes

September 1992 By Yasushi Ichikawa