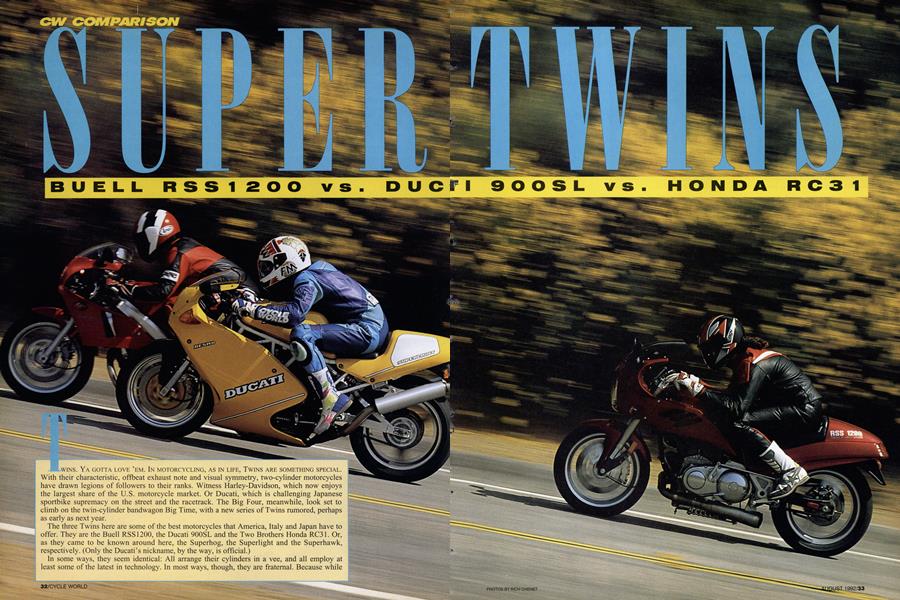

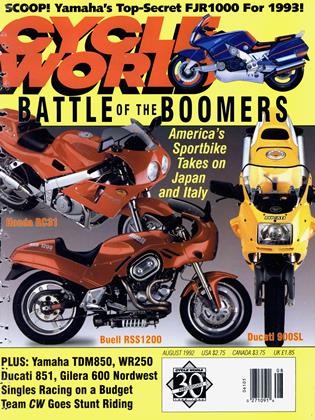

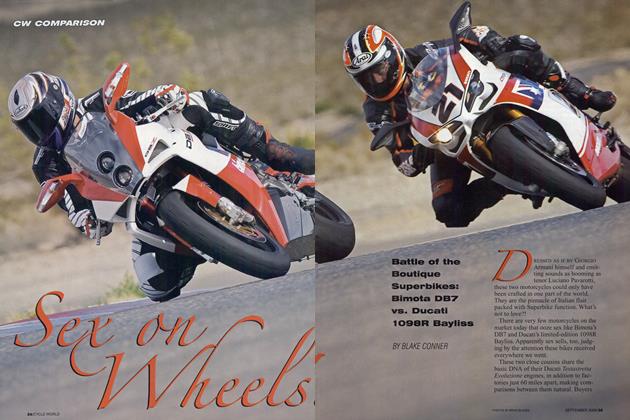

SUPER TWINS

CW COMPARISON

BUELL RSS1200 vs. DUCTI 900SL vs. HONDA RC31

TWINS. YA GOTTA LOVE ’EM. IN MOTORCYCLING, AS IN LIFE, TWINS ARE SOMETHING SPECIAL. With their characteristic, offbeat exhaust note and visual symmetry, two-cylinder motorcycles have drawn legions of followers to their ranks. Witness Harley-Davidson, which now enjoys the largest share of the U.S. motorcycle market. Or Ducati, which is challenging Japanese sportbike supremacy on the street and the racetrack. The Big Four, meanwhile, look set to climb on the twin-cylinder bandwagon Big Time, with a new series of Twins rumored, perhaps as early as next year.

The three Twins here are some of the best motorcycles that America, Italy and Japan have to offer. They are the Buell RSS1200, the Ducati 900SL and the Two Brothers Honda RC31. Or, as they came to be known around here, the Superhog, the Superlight and the Superhawk, respectively. (Only the Ducati’s nickname, by the way, is official.)

In some ways, they seem identical: All arrange their cylinders in a vee, and all employ at least some of the latest in technology. In most ways, though, they are fraternal. Because while all three are children of the same parental concept, they are generations apart in execution.

First, while you can walk into any Buell/Harley-Davidson or Ducati dealership and place a deposit on an RSS or SL, you can’t just order up an RC31-at least not directly from Honda. Not yet, anyway. In car terms, the RC31 is a kit: a merger of Honda Hawk and performance parts from Two Brothers Racing (2890 Via Martens, Anaheim, CA 92806; 714/632-8820). But it can be argued that this is the bike Honda should have built instead of the confused, not-quitea-standard, not-quite-a-sportbike Hawk GT647, introduced in 1988 and discontinued this year due to lackluster sales. Indeed, if one believes the latest scuttlebutt, an enlarged, more sharply focused Hawk similar to the Two Brothers bike is already in the works.

So, what’s so special about these particular Twins? Isn’t the Ducati 851 the reigning performance king of production two-cylinder motorcycles? Yes, it is (see riding impression, page 40). But while the 851 will be produced and sold in limited numbers, it is far less limited than the bikes shown here. According to Erik Buell, there will be only 130 or so of his HarleyDavidson-powered sportbikes assembled this year, about half of them RSS models. Ducati spokesmen are tightlipped about the number of 900SLs that will be imported to America, but considering that the Superlight is a limited-production version of the 900 Supersport, a good estimate would be less than 200. And the RC31...well, Two Brothers owners Craig and Kevin Erion are perfectly willing to sell parts to any and all Hawk owners, the number of which American Honda refused to disclose. Ten thousand would be a good guess.

Much has been written about the joys of twin-cylinder motorcycling-the ease with which one can cruise, at an unhurried cadence, while basking in waves of torque and ignoring the shift lever. But if Twins have another reputation, it is for vibration. Owners of parallel-Twin Britbikes need not be reminded of how their machines shake, rattle and roll. VTwins are in no way immune to this buzzing, but these three Twins are all surprisingly smooth. And each goes about quelling vibration in a different manner.

The Ducati, by its very nature, has perfect primary balance. Its cylinders are set at a 90-degree angle, the front one jutting out horizontally toward the front wheel and the rear one located vertically beneath the fuel tank. Its designers lovingly refer to this as an “L-Twin.” With its connecting rods sharing a common crankpin, the motion of one piston is offset by the motion of the other.

The Honda also dampens vibration by design. Though its cylinders are splayed 52 degrees, it utilizes offset crankpins to effectively fool the engine into acting like a 90-degree V-Twin. The end justifies the means.

Harley-Davidson engines, such as the 45-degree V-Twin Evolution Sportster employed in the Buell, are notorious shakers. When solidly mounted like they are in the stock Sporty frame, they vibrate enough to shake your fillings loose-especially at high speeds.

Harley knows this, and for a long time has rubber-mounted most of its 1340cc Big Twins. Erik Buell knows this, too, but he went one better than mere rubber mounts; the bikes that bear his name use a patented Uniplanar mounting system. This configures the engine and swingarm as a unit, bolted together with a pair of aluminum plates. The engine, in turn, is attached to the frame via a system of rubber dampers and Heim-jointed rods, and is free to shake up and down without transferring any of that energy into the frame. To make the isolation complete-and to make best use of available space-the Buell’s rear shock is mounted horizontally, beneath the bike, its leading end bolting to the engine cases.

Buell refers to his frame as Geodesic, meaning “light, straight structure.” More often, this design is referred to as a spaceframe. The Ducati Superlight utilizes a very similar chassis design, except that its engine is solidly mounted and load-bearing, with its swingarm pivoting in the rear of the engine cases. The Honda, meanwhile, uses a more modern twin-spar aluminum-alloy chassis, with a singlesided swingarm derived from endurance racing. Neither the Ducati nor the Honda employ any sort of shock linkages; instead, their single shocks are bolted directly between the swingarm and frame, cantilever style.

In sporting use, all three of these bikes fare well, even if they go about their chores quite differently. The Buell is the most different. The first Buells were hardcore sportbikes, with bulbous, all-enclosing bodywork, solo seats and demanding riding positions. They were fitted with Works Performance shocks, and Marzocchi forks equipped with Buell’s own anti-dive system and fourpiston brakes. The first of the Buells, called the RR1000, was powered by Harley’s iron-barrel XR1000 motor. When supplies of those engines dried up, Buell fitted 1200cc Evolution Sportster motors, and changed the name to RR1200.

Times, and Buells, change. The latest Buell, the RSS1200 shown here, utilizes the same basic engine/frame design as the half-fairing RS1200, introduced in 1990 and still available. But where the RS features a funky flipup dual seat and hideous hindquarters, the RSS has a sleek solo seat and is

one of the most striking motorcycles on the market. The RSS turned more heads than any stock streetbike we’ve tested recently, more even than the bright-yellow Ducati. Even non-motorcyclists stopped to ask what it was.

Sitting on the Buell, a rider finds himself very far rearward, with a long reach to the clip-on handlebars-even though these are positioned atop the top triple clamp and arch back toward the rider, resembling a pair of water faucets. Grips, levers and instruments are all standard Harley issue, which is to say big and cumbersome. Knees fit into indents in the tank sides and rest against pads on the fairing lowers, and buttocks conform to the contours of the Corbin saddle. Footpegs are moderately high and rearset; only long-legged riders complained of limited legroom.

The Buell’s riding position takes some getting used to, but once he’s adapted to it, a rider can go surprisingly quickly-especially considering the motor is basically stock. With the Buell’s stout frame and White Power inverted fork, racerish frame geometry and wide Dunlop K591 Sport Elite tires, steering is extremely light and handling taut. This is a motorcycle that changes direction easily, in spite of its heavy (by Twins standards) 473-pound dry weight. Another new feature on the RSS is the front brake, a machined-aluminum six-piston caliper and 12.8-inch castiron disc made in America by Performance Machine. Buell decided to use a single front disc in the interest of less rotating mass and unsprung weight, both boons to handling. While the new brake offers excellent stopping power and good feel (stainless steelbraided brake lines are standard), our testbike’s brake overheated under hard use. The lever would then come back to the handlebar until it was pumpedup a few times. With the Buell’s rearward weight bias, maximum stopping power is achieved if the rider also uses the rear brake, a twin-piston unit made in the U.S. by Gambler.

Our only gripe with the Buell’s handling concerned the White Power rear shock, which we never could get dialed-in. This operates in tension, rather than compression; when the rear wheel encounters a bump, the shock extends. Therefore, the shock’s compression and rebound damping adjusters swap roles on the Buell. We felt that the range of damping adjusment-especially rebound damping-was too limited, and mid-corner bumps upset the chassis. We did, however, appreciate the shock’s hydraulic spring-preload adjuster, which changes with the simple twist of a knob. It’s a good thing, too, because we found the Buell’s shock to be very sensitive to rider weight; taking a few moments to set sack greatly improved ride quality.

Every Buell comes standard with a SuperTrapp exhaust system and silencer. As a result, a Buell sounds better and feels stronger than a stock Sportster; our RSS made 61 horsepower at 5500 rpm on the dyno. With its rider sitting over the rear wheel, the Buell wheelies easily-something a regular Sporty is reluctant to do. The 1203cc ohv pushrod motor lets the Buell accelerate smartly, if not briskly, from 2000 to 6000 rpm, at which point a rev limiter retards ignition timing. Our testbike recorded a 12.41 -second/109-mph quarter-mile and 124mph top speed, compared to a stock Sporty 1200’s 13.00-second/99-mph dragstrip and 115-mph top-speed figures. The Buell’s broad spread of power, coupled with the lack of vibration afforded by the engine-isolation

system, can be deceptive; it’s easy to find yourself revving the motor past redline. To keep check on the motor’s temperature, the RSS has been fitted with an oil cooler and accompanying oil-temperature gauge.

Enough about the “Harley.” What about the others?

Recently introduced to these shores, the Ducati 900 Superlight is essentially a 900 Supersport with different styling and a few weight-saving components. Both the SS and SL are powered by the same 904cc air-and-oil-cooled powerplant, and both feature Ducati’s famed desmodromic positive valve-actuation system, which forgoes valve springs and uses rocker arms to open and close each cylinder’s two valves. Though our testbike was a European model (replete with speedometer marked in kilometers per hour and a headlight on/off switch), tuning specifications were claimed by Cagiva North America to be the same as the 900SS sold here. On the dyno, our testbike made 76 horsepower at 6750 rpm.

The only difference between the SS and SL motor is the SL’s ventilated clutch cover, which in no way improves the 900’s horrible, squawking dry clutch, nor its limited range of engagement.

As for the rest of the bike, that’s a different story. The Superlight, in contradiction to its name, weighed just 5 pounds less than the 900SS on the certified CW scales^l-09 vs. 414 pounds dry. This small weight loss was achieved through use of a solo seat, carbon-fiber fenders and composite wheels featuring magnesium Marchesini hubs and spokes bolted to aluminum Akront rims. The one-piece seat/tail attaches to the frame with Allen bolts, so the under-seat toolkit is accessed by use of an Allen wrench that attaches to your key ring. Other changes include more upswept mufflers and Brembo Goldline calipers with full-floating rotors.

Given its specification, you would expect the Superlight to work like the standard Supersport. And you’d be right. The SL has the same wide powerband, and posted near-identical performance numbers as Cycle World’s 1991 test 900SS, recording a l 1.74-second/l 13-mph quarter-mile and a 130-mph top speed. The only really noticeable difference concerned the rear shock. We felt last year’s SS had a tad too much compression damping and a tad too little rebound damping, which let the bike wallow in high-speed sweepers. The SL, however, displayed no such tendency, even in fast, bumpy corners. Its pair of fourpiston front brakes work magnificent ly, even if lever feel is a little mushy. And its tires, new-generation Michelin A89/M89Xs, are a match for the chas sis. Light, nimble and secure, the Superlight is simply one of the best handling motorcycles in the world.

Which brings us to the Honda RC3 1, so-named, as was the RC3O superbike, for the prefix on its steering-head serial number. Most folks would recognize this bike as a Hawk, albeit a heavily breathed-on one, and it represents what many insiders believe may soon be a production Honda V-Twin sportbike. Fitted with clip-on handlebars and RC3O fairing and tailpiece, and based on the bike Kevin Erion took to an AMA Pro Twins GP2 championship in 1989, it is certainly the most capable twin-cylinder sportbike ever to emerge from Janan.

-Considering that the 647cc Hawk would be going up against bikes that displaced 900 and 1200cc, it was given a slight motor massage by Two Brothers. Engine internals were left stock, though, with modifications focused on intake and exhaust. HRC slides, springs and diaphragms were installed in the Hawk's stock 36.5mm CV carburetors, the carbs were rejet ted, individual foam air filters substi tuted for the stock airbox, and nickel-plated 2-into-i exhaust system fitted, upping the Hawk's output from 47 horsepower at 7500 rpm stock to 58 horsepower at 8250 rpm. -

On the chassis side, the front wheel was widened to 3.5 inches to accom modate the latest in race-bred rubber, and both wheels were shod with Bridgestone Battlax radials. The fork was revalved for increased compres sion and rebound damping, an Ohlins shock fitted, steel-braided brake lines added, and that was that.

As small as a stock Hawk feels, the RC31 feels even smaller. Due to its lower handlebars and solo seat, a tall rider can barely get his helmet behind the bubble. By comparison, the Ducati feels roomy, the Buell rangy. Even with its performance mods, the Hawk feels pretty slow-its 12.48 secondllO5-mph dragstrip numbers and 124-mph top speed numbers were almost identical to those of the Buell-and it is the hardest of these three to ride fast, requiring that the motor be wrung out and the transmission rowed. As delivered, the redone suspension was way too soft at both ends. We installed a stiffer shock spring to get a handle on the rear, but never did sort out the front. Given some time, we’d probably cut a few coils off the stock springs, add a spacer of the same length and have another go at it.

Nevertheless, the RC31 is still plenty fun to ride fast. Provided the rider doesn’t try to brake too late for a corner and upset the soft front end, he can carry incredible entrance speed. As with the Buell and Ducati, cornering clearance is seemingly unlimited; on the street, we never touched a thing down. The Hawk’s single front disc brake performs incredibly well; in fact, the Hawk bested the other two bikes in our brake testing, though that was probably due more to its light, 383pound dry weight as to superior brake components.

The Hawk shook its head occasionally, probably a result of its soft fork springs, but other than that, we didn’t have any handling complaints. Give it a bigger motor, firm up the suspension, make it a little more spacious, and replace some of the cobby parts found on this “prototype” with Honda’s customary excellent fit and finish, and you’d have a world-class motorcycle, easily a match for the other two bikes here.

Which begs the eternal query: Which one’s best? Tough question, and one for which there’s no easy answer. If price were the issue, it would have to be the Honda. Shop around, and you might find a brandnew, leftover Hawk for as little as $3000. Add to that a few grand’s worth of parts from Two Brothers, and a Superhawk would still cost significantly less than the $10,000 Ducati or $16,000 Buell. Of course, you’d have to provide your own labor, or find someone willing to build an RC31 for you.

If you’re a Harley guy, or looking for an American sportbike or just want a bike that will turn more heads than Sharon Stone in a short skirt, the Buell’s your bike. Want more performance? Simple. Dial up any of the numerous Harley hot-rod outfits dotted across this great land. But if you’re looking for the Twin that simply works best, while still having plenty of crowd-pulling appeal, check out the Ducati 900 Superlight. No, it probably isn’t worth $1300 more than a regular 900SS. Unless you measure a motorcycle in terms other than outright performance, that is.

Which, if you stop to think about it, is probably why you’re shopping for a Twin in the first place. □

BUELL

RSS1200

$15,995

DUCATI

900SL

$9800

HONDA

RC31

HORSEPOWER/ TORQUE