PRIDE & JOY

DON CANET

READERS’ RIDES IN THE SPOTLIGHT

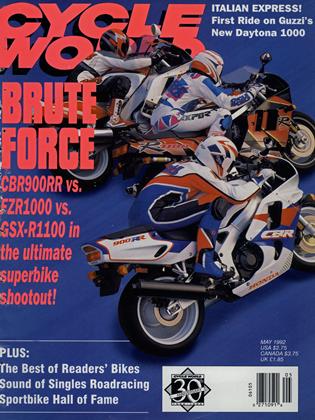

LIKE ALL GOOD IDEAS, THIS ONE WAS SIMPLE. WHY NOT invite Cycle World readers to exhibit their personal machines at motorcycle shows around the country?

So we ran a full-page announcement in the back of the magazine soliciting entrants. The Cycle World Readers’ Collection, it was called, and we arranged with Edgell Expositions to have display space at seven of its nationwide International Motorcycle Shows. Made up of bikes from each local area, there would be 10 different classes at each show, reflecting CW's broad editorial coverage. Staff members would pick the best-in-class for each category and there would also be a Peoples’ Choice award, voted on by show-goers.

The response was overwhelming. At some shows, we even had to decline entries for lack of space. And the motorcycles were breathtakingly beautiful, with everything from customs to classics to vintage bikes to racers to touring rigs represented.

On the following pages, you’ll find the class winners from the Anaheim, California, show. We chose this venue to illustrate the Readers’ Collection Series because it’s right in our own backyard, close to the CW photo studio. But, rest assured, the machines at the other shows were equally as enticing. Of course, if you attended any of the shows, you already know that.

If not, well, we hope to see you next year.

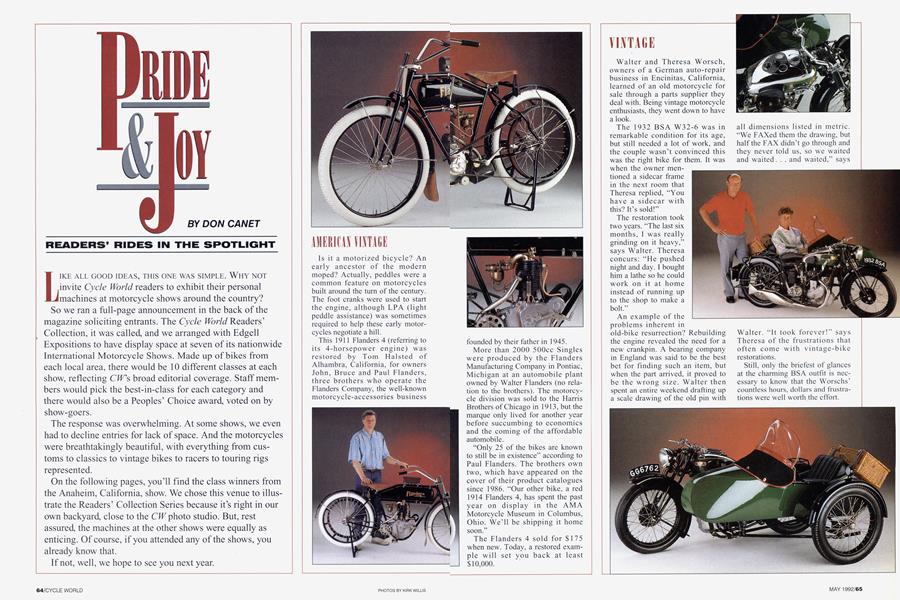

AMERICAN VINTAGE

Is it a motorized bicycle? An early ancestor of the modern moped? Actually, peddles were a common feature on motorcycles built around the turn of the century. The foot cranks were used to start the engine, although LPA (light peddle assistance) was sometimes required to help these early motorcycles negotiate a hill.

This 1911 Flanders 4 (referring to its 4-horsepower engine) was restored by Tom Halsted of Alhambra, California, for owners John, Bruce and Paul Flanders, three brothers who operate the Flanders Company, the well-known motorcycle-accessories business founded by their father in 1945.

More than 2000 500cc Singles were produced by the Flanders Manufacturing Company in Pontiac, Michigan at an automobile plant owned by Walter Flanders (no relation to the brothers). The motorcycle division was sold to the Harris Brothers of Chicago in 1913, but the marque only lived for another year before succumbing to economics and the coming of the affordable automobile.

“Only 25 of the bikes are known to still be in existence” according to Paul Flanders. The brothers own two, which have appeared on the cover of their product catalogues since 1986. “Our other bike, a red 1914 Flanders 4, has spent the past year on display in the AMA Motorcycle Museum in Columbus, Ohio. We’ll be shipping it home soon.”

The Flanders 4 sold for $175 when new. Today, a restored example will set you back at least $10,000.

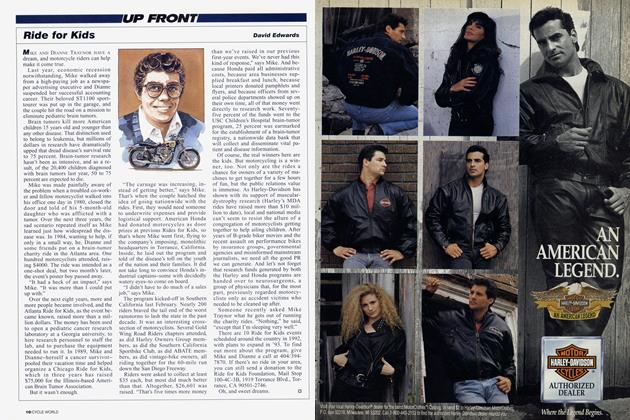

VINTAGE

Walter and Theresa Worsch, owners of a German auto-repair business in Encinitas, California, learned of an old motorcycle for sale through a parts supplier they deal with. Being vintage motorcycle enthusiasts, they went down to have a look.

The 1932 BSA W32-6 was in remarkable condition for its age, but still needed a lot of work, and the couple wasn’t convinced this was the right bike for them. It was when the owner mentioned a sidecar frame in the next room that Theresa replied, “You have a sidecar with this? It’s sold!”

The restoration took two years. “The last six months, I was really grinding on it heavy,” says Walter. Theresa concurs: “He pushed night and day. I bought him a lathe so he could work on it at home instead of running up to the shop to make a bolt.”

An example of the problems inherent in old-bike resurrection? Rebuilding the engine revealed the need for a new crankpin. A bearing company in England was said to be the best bet for finding such an item, but when the part arrived, it proved to be the wrong size. Walter then spent an entire weekend drafting up a scale drawing of the old pin with all dimensions listed in metric. “We FAXed them the drawing, but half the FAX didn’t go through and they never told us, so we waited and waited. . . and waited,” says Walter. “It took forever!” says Theresa of the frustrations that often come with vintage-bike restorations.

Still, only the briefest of glances at the charming BSA outfit is necessary to know that the Worschs' countless hours, dollars and frustrations were well worth the effort.

SPECIALS

Would anybody like to own a Suzuki RGV500-the same type Kevin Schwantz rides in GPs-as a streetbike? If history is any indication, you may have a shot at such a dream machine in, say,

10 to 20 years.

Dan Cragin, a 32-year-old auto mechanic from Santa Monica, California, is the proud owner of a Suzuki Seeley 750, a piece of racing history that he’s restored and converted for street use. Cragin found his obsolete racebike tucked away in somebody’s garage, still in competition trim, but in dire need of crash-damage repair.

The bike uses a Seeley Formula 1 roadrace chassis, one of only three imported to the U.S. It is powered by the liquid-cooled, two-stroke Triple from a Suzuki GT750, that amiable mid-Seventies roadster known as the “Water Buffalo.” But the GT750 had a race history, as well. Suzuki TR750s, as the factory-prepped racebikes were called, made their presence known at Daytona, exceeding 170 mph at the super speedway in the capable hands of factory riders Gary Nixon, Barry Sheene, Paul Smart and Jody Nicolas.

Cragin’s GT engine has been modified to meet TR specs, which makes for some interesting Sundaymorning rides. “It’s a real hot rod,” says Cragin. “But it’s got heavy flywheels and comes on the pipe early, so it’s real torquey. You just aim it and shoot.” The odds of ever finding a works RGV500 at a bargain-basement price probably are very long. Just the same, keep your eyes open if you’re poking around some junk heap in the 21 st century, because beneath the cobwebs and dust may be a fairing bearing the familiar Pepsi or Lucky Strike logo. Well, if your luck is anything like Dan Cragin’s, that is.

CUSTOM HARLEY-DAVIDSON

For 57-year-old Marv Marter, taking his 1988 Harley-Davidson Softail in for a routine tune-up rapidly escalated into a modifications marathon.

“I took the bike to Chris Burchinal’s Performance in Anaheim, California, for an oil change and service” explains Marter. “Then, Chris and I talked about changing a few things-a couple thousand dollars worth. I picked the bike up 14 months later.”

Not an inch of the bike had been left untouched. Its list of engine and chassis components reads like a roster of aftermarket industry all-stars. “Not many Harley parts on it at the moment,” says Marter of his $45,000 labor of love.

“Today, the average guy would pay 55 to 60 grand duplicating my bike,” Marter continues. “A lot of the parts were built by friends of mine, which I don’t consider a cost. Chris’ labor, for example, is $40 per hour, and I guarantee you he made only about $8 per hour by the time he was done. It got to be an ongoing thing.”

Burchinal, who has been building custom Harleys for three years, agrees. “We wanted something nobody else had, something you couldn’t just order out of a catalog.

It was a lot of trial and error,” he says. The end result, though, is an absolutely stunning machine that’s won all six of the local shows it has entered, and BurchinaTs now markets many of the custom bits and pieces found on the bike.

“The way I see it,” says Marter, “Chris is kind of the unknown Arlen Ness.”

CLASSIC JAPANESE

Back in the late Sixties, a boy in his early teens daydreamed of owning the new dual-purpose bike he was perched upon in a Yamaha dealer’s showroom. To him, and many others at the time, the 305 Big Bear Scrambler was the ultimate mount. With its five-speed, twostroke Twin producing a claimed 31 bhp, its off-roau capability and a top speed in excess of 90 mph, it’s easy to see why the 305 attracted the lad.

It was a long time coming, but about a year ago Scott Brown-now a 38-year-old motorcycle-salvage man from Escondido, California-purchased the object of his boyhood desires. But the past quarter-century had been much kinder to Brown than to the 1967 street scrambler, which suffered from rust, corrosion and various missing parts.

Restoration commenced with the purchase of a second Big Bear as a donor bike.

“The hardest part was finding a lot of the little parts. I got to the point were I was trying to buy parts all over the country one piece at a time,” says Brown. Then, he hit the Motherlode in his own backyard. “I found, right in the local area, a dealer inventory of obsolete Yamaha parts. I went through it and found all kinds of neat stuff that really helped finish the bike.”

Brown arranged a bulk purchase of the entire inventory, which included 13 tank badges, the Holy Grail of classic-Japanese restorers.

With a stable of 25 early Japanese motorcycles-many of which are unrestored-Scott Brown could well be on his way to becoming an obsolete-parts kingpin.

CLASSIC

Ask John Caraway, a devoted member of the Vincent Owners Club, Northern California Section, if good things do indeed come to those who wait, and he’s likely to tell you of the prolonged courtship with his beloved 1951 Vincent Series C Rapide.

“This bike was restored by Jeff Sierck about 14 years ago. I first saw it 12 years ago when I moved to Sacramento, California, and that’s how long I’ve waited for him to be ready to cut loose of it,” says 53year-old Caraway, a labor-dispute mediator who fell in love with Vincents some 30 years ago when he first saw one of the legendary British V-Twins.

When questioned of the Vincent’s fabled performance, Caraway replies, “Its handling is excellent, very British and precise, but with engine characteristics more like a Harley. It has bags of low-end torque.” And does that assessment come from hands-on knowledge or hearsay? “I won’t own a motorcycle I don’t ride,” Caraway says. “It’s my feeling that’s why Mr. Vincent put wheels on the bottom.”

Caraway’s side business, Mostly British M/C, keeps him plenty busy putting the life and shine back into vintage iron. He’s currently restoring a Norvin (a Norton-framed, Vincentpowered café bike), a Model-7 Norton and a Matchless Typhoon, but that doesn’t stop him from regularly exercising the Rapide.

“I have several bikes, but when I go out to the garage, this is the one I want to ride. I can’t take credit for restoring it, but I’ll take credit for having it the rest of my life,” he says.

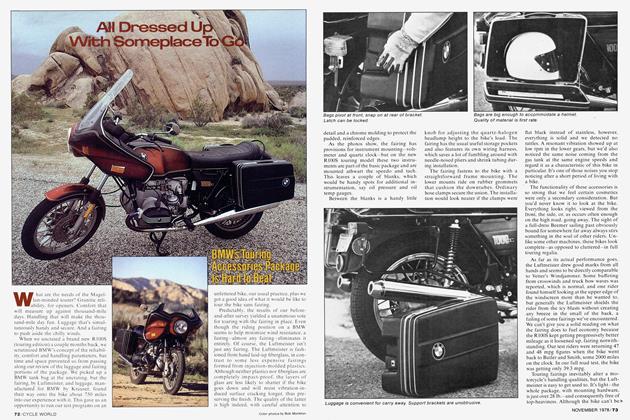

TOURING

Lonnie Casper, 40, an optician, and his wife Linda, a registered nurse, love to ride. Their 1989 Honda Gold Wing was purchased used with 20,000 miles on it to replace the Caspers’ aging 1983 Gold Wing.

When asked how often they ride their GL1500, Lonnie quickly answers, “This is my only mode of transportation. I ride it to work every day, rain or shine. Linda has a small car that she uses sometimes, but we prefer using the bike when we can. We’ve ridden over 30,000 miles the past year.”

A beaming Linda adds, “We even use the bike to go grocery shopping. We go on a ride someplace every weekend and all of our vacation time is spent traveling on the Gold Wing.”

Not surprisingly, this high-mileage couple has tailored their mount more for function than flash. With the exception of some added chrome trim, pinstriping and fairing lights, modifications to the Caspers’ Honda are aimed directly toward passenger comfort. An intercom eliminates back pounding, shouting and hand signals.

“The intercom really adds to the enjoyment of traveling on a bike. And I really like the extra footrests that we’ve added. The armrestsZ are nice, too,” says Linda. And footboards placed outside of the Wing’s fairing let Lonnie stretch out during long days on the road.

What’s next for the 50,000-mile Honda? “Maybe some more chrome and pinstriping,” says Lonnie. Linda, smiling, nods in agreement.

AMERICAN CLASSIC

At the end of WWII, many military surplus motorcycles marched into civilian duty. This 1943 Indian 741-B Military Scout, owned by Dennis Stoeser, a 47-year old Mercedes-Benz mechanic from San Diego, California, never saw action in the Big One, but has 17,000 peacetime miles to its credit.

Stoeser purchased the bike six years ago from the original owner, who had bought it brand new through a Los Angeles-area Indian dealership.

“It was a 95 percent complete and running bike when I bought it,” says Stoeser of the three-speed, 500cc VTwin-those in the know call the engine a “Thirty-Fifty,” referring to its 30.50 cubic-inch displacement. After riding the Scout for a couple of weeks, and mastering its lefthand throttle and right-hand shift knob, Stoeser decided to totally restore the machine.

He handled most of the work himself, farming out the more difficult tasks. The saddlebags, for example, were reproduced by an old-time leather man in Idaho, who spent a year searching for the right weight and grain of leather, then took the original bags apart and used them as a pattern.

Stoeser painted everything a correct dull-olive drab, but later saw another Army Indian painted in glossy “parade” colors, and decided to have his bike repainted.

“Some will say they didn’t do it this way, but other Indian historians say, yes, they did. Whatever the case, it definitely looks better this way,” says Stoeser, who is quick to point out that his Indian is not just a showpiece. “It starts and runs as good as it looks” says Stoeser, who enjoys an occasional reconnaissance ride aboard his Military Scout.

“It may not be fast, but it’s sure a head-turner,” he says.

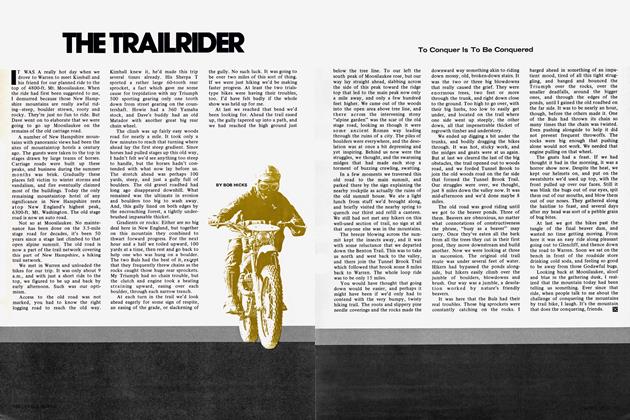

COMPETITION

“I’ve been into Kawasaki Triples for many years,” says Tom Sherman, a 32-year-old plastics technician. “I had a ’69 500 Mach III and was really interested in building a replica of an H-1R.”

While gathering information on the legendary two-stroke production roadracer, Sherman learned of a H1R in storage about five miles from his Simi Valley, California, home.

“We jumped in the car and raced over there, and sure enough, it was the real McCoy,” says Sherman, who immediately shelved plans for building a replica racebike, and set about trying to buy the genuine article from its suddenly reluctant-tosell owner.

Pulling teeth may have been easier.

“It was about a 12-month process getting the guy to commit to selling it,” says Sherman. “He had a couple friends who became interested in buying the bike once the word got out, but in the end, being a man of his word, he sold the bike to me for $3500.”

It would be another year of gathering information before Sherman tore the bike down to the frame and rebuilt it from the ground up.

Luckily, the engine was in excellent condition, and required only a thorough external cleaning.

“I plan to ride it this year,” says an eager Tom Sherman, who intends to recreate the Suzuki -Kawasaki roadrace battles of the 1970s with the owner of our Specials-class winner. “Dan Cragin and a few other friends with similar kinds of bikes will be joining me for some fun laps and friendly bench racing at a local race track.” says Sherman.

SPORTBIKE

For Mike Reichard of Corona, California, taking his highly modified 1986 Suzuki RG500 Gamma out for a spirited Sunday romp is a good way to let off steam.

“It’s a lot safer going riding on the weekend than it is working on Monday,” jokes Reichard, a 34-year-old high-rise glazier by trade.

“Most of the guys I ride with have GSXR1 lOOs-they’re fun to toy with,” says Reichard, who draws on his past motocross and short-track racing experience to capitalize on the twostroke, Canadian-spec Gamma’s power-to-weight advantage over the big-bore four-strokes.

“And even if I’m not the fastest rider on the mountain, guys like to follow me for awhile to smell a little oil and hear the exhaust crack before going around,” he says.

It was following a trip to Europe during which he and wife Peggy attended four grand prix races that Reichard knew he had to have a 500cc two-stroke of his own. He found a used Gamma in the Cycle News classifieds, but wasn’t quite satisfied with it in stock form. Modifications commenced immediately, and now include GSX-R wheels and brake rotors, Kawasaki ZX-11 front calipers, a Fox shock, a JMC swingarm, GSX-R-style dual headlights, a Corbin seat and custom paint.

When probed about his next planned modification, Reichard replies, “I’d like to get another one and make it clean but not so showy, try to make it faster and lighter.” Stands to reason: Any selfrespecting GP rider has a backup bike waiting in the wings.

PEOPLES’ CHOICE

Seems a bit odd that the crowd favorite at the Anaheim Show should be a machine that resembles an oversized scooter with full-coverage bodywork, not so unlike the recent Honda Pacific Coast. Where were all those people a couple years ago when the ill-fated PC was dropped from Honda’s lineup due to a lack of popularity?

All of that is of no concern to Dr. Tas Toth-Tevel, a 38-year-old chiropractor from Thousand Oaks, California. Dr. T’s 1955 Vincent Black Prince, winner in the People’s Choice voting by a wide margin, draws attention wherever it goes, and, as Toth-Tevel eloquently puts it, “The Vincent was a true superbike without equal until the late ’60s when the Honda Four and Norton Commando became available.”

But the Black Prince has more than speed in its comer. In fact, Toth-Tevel prefers the Black Prince to his new Harley-Davidson Sportster for longer hops.

“This past summer, she was ridden without incident from San Francisco to Lake Tahoe down to Maraposa below Yosemite National Park to the International Vincent Rally. Cmising speed was a steady 65, with bursts of 90 here and there.”

In its day, the Vincent Black Prince was overpriced and not very popular, but is now considered one of the most collectible British classics. Kind of makes you want to pick up a Honda Pacific Coast at reduced cost and sock it away for a rainy day, doesn’t it?