AT LARGE

Makanna's Message

Steven L. Thompson

LIKE MOST FIRST-SEASON RACERS, I was obsessed by the sport in my Novice year. Everything took back seat to racing-work, school, even love. The discovery of just how fast you can go, and of just how delicious the competitive atmosphere really is, flat blows everything else out of your mind. Well, my mind, anyway, back in that spring of 1967. When I stepped onto the track at Cotati in March for my first race on a YR1 Yamaha, the world split in two segments: Racing, and Everything Else.

Or so it seemed. Until, only a few races into the '67 season, something happened to bring the two worlds back together again, like U-235 atoms colliding. It was Art.

Not Art Baumann, who was winning everything that Ron Grant wasn't, but the dictionary's “Art: the conscious use of skill, taste and creative imagination in the practical definition or production of beauty." The bringer of this art was Phil Ma kan na.

Phil was an art professor at Cal Berkeley. But he was also an AEM Expert roadracer, a serious, sponsored East Guy who impressed me deeply at Vacaville and Cotati. But it wasn't what he did on the track that changed my point of' view; it was w hat he did in the Student Union.

I was 19 when 1 strolled through the Student Union one Monday in the spring of' '67. and suddenly halted as if pole-axed. Now, 19 is a weird age for men-children. We're far more impressionable than we like to admit, impulsive, statistically at our physical peak and hugely hormone-driven. (Which is why armies usually include vast numbers of 19year-olds.) What we are not. usually, is ready to question our own assumptions. But what assailed me in the Student Union did just that.

Stretching ¿dong the length of the downstairs hall was an exhibit of motorcycles. Racing motorcycles, mostly. 1 backtracked and read the exhibit poster, which had been penned, as the exhibit had been designed. by Phil Makanna.

The gist of his exhibit was this: Motorcycles can be art. Not art-like, or almost art. But art. period. As a guy with one academic foot in astrophysics and the other in Art with a capital A. this floored me. 1 loved machinery, the way most airplane/ car/bike/boat freaks my age did. mavbe more. But motorcycles as legitimate Art? Art was made by guys like Vermeer and maybe even Jackson Pollock. Not by BSA. Yamaha. Honda and Harley-Davidson.

Being 19, it never occurred to me to track Makanna down and make him explain all this. When you're 1 9. you don't do that kind of stuff. I just wandered awav. and Makanna's notion began boring into my brain, willy-nilly. As time passed, I wondered. and read, and thought, but without Makanna. 1 couldn't know why he thought bikes were Art.

Sixteen years later. 1 finally pigeonholed him. at Harlingen. Texas, home of the Confederate Air Force. 1 was editing an aviation magazine, and he was now The Famous Phil Makanna. creator of the (¡hosts series of almost otherworldly WW1I warbird books and calendars. C ould we ta 1 k? I asked him. Eater, he said.

“Eater" took another seven years. But finally, tracked down in San Francisco, Phil explained how bikes become Art.

Chances are. you already know it. maybe without even thinking about it. When we buy “classic" bikes— w hen we elevate certain machines to almost mystical status—we are not simply celebrating their race victories or engineering. We're responding to them as Art.

Now. the legions of art historians and art critics churned out bv liberalarts colleges over the last seven decades wrestled with the matter of whether a “manufactured" object can be Art until the pro and con sides gave up and shifted their arguments to more fertile ground. Leaving motorcycles to us. and art people like Phil. And we know, without even discussing it. that sometimes, a machine transcends the demands of marketing or manufacturing and simply is Art.

The fact that a bike is at least nominally functional does not change this. Indeed, the true magic of motorcycles is that they blend tactile and visual arts with kinetic art to become something you relish whether moving or not. Double-whammy Art.

Future ages will value the best expressions of skill merged w ith imagination to produce beauty on two wheels whether or not the engines ever tire again. Tike our seemingly eternal love affair with Triumphs or V-Twin Indians. Harleys and Brough-Superiors, more is happening in our brains when we look at these things than just habituated and acculturated response.

In his book Art and the Automobile, D.B. Tubbs describes the paucity of attention given to cars and driving and all the related issues by “serious" artists. Theories abound. Naturally, I have my own, inspired all those years ago by Phil Makanna.

My view is that Art has been democratized by manufacturing. Just as a motorcycle is a musical instrument, it's also a potential piece of artwork. As it leaves the factory, it may be gessoed canvas or a fairly complete painting, depending on the genius or lack of it in its making. But the art really starts w hen we get it home. The ride is art, and so is what we do with a motorcycle when we transform it from a series-built device to something unique. We're the artists, the machine our canvas.

If you think of Art as something that hangs on a wall or stands on a pedestal, you may never realize what it is you've got in your garage. On the other hand, if you really listen to Makanna's message, next time you look at your bike, you may see something that can change your life. Which is, in the end. what Art is all about. On two wheels or none.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

September 1991 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

September 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1991 -

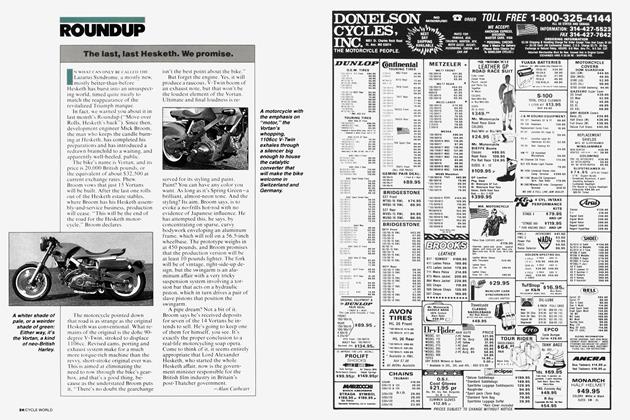

Roundup

RoundupSupersport Ducks?

September 1991 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupBell Bounces Back

September 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupThe Last, Last Hesketh. We Promise.

September 1991 By Alan Cathcart