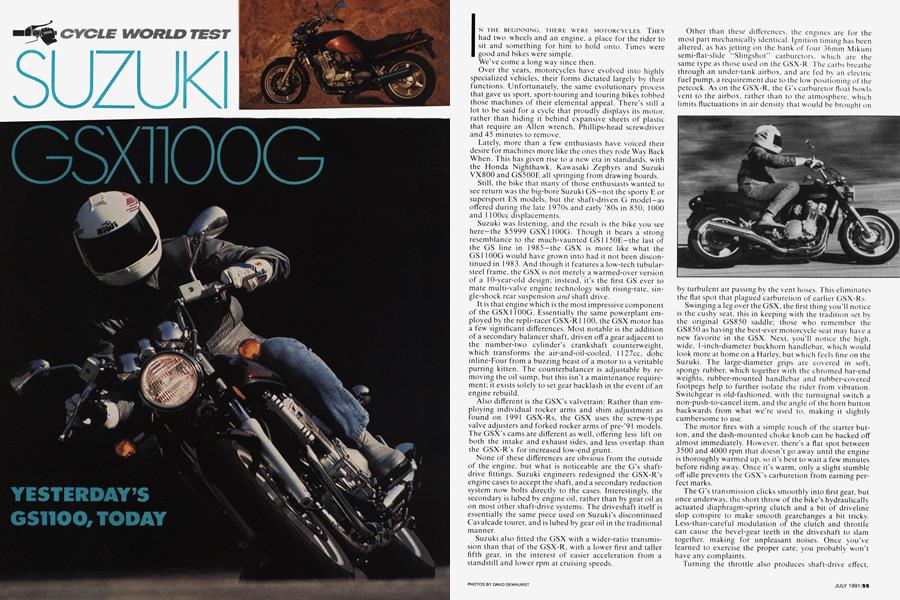

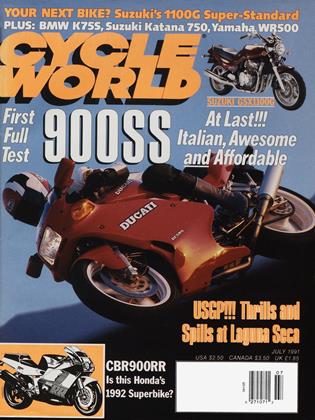

SUZUKI GSX1100G

CYCLE WORLD TEST

YESTERDAY'S GS1100, TODAY

IN THE BEGINNING, THERE WERE MOTORCYCLES. THEY had two wheels and an engine, a place for the rider to sit and something for him to hold onto. Times were good and bikes were simple.

We’ve come a long way since then.

Over the years, motorcycles have evolved into highly specialized vehicles, their forms dictated largely by their functions. Unfortunately, the same evolutionary process that gave us sport, sport-touring and touring bikes robbed those machines of their elemental appeal. There’s still a lot to be said for a cycle that proudly displays its motor, rather than hiding it behind expansive sheets of plastic that require an Allen wrench, Phillips-head screwdriver and 45 minutes to remove.

Lately, more than a few enthusiasts have voiced their desire for machines more like the ones they rode Way Back When. I his has given rise to a new era in standards, with the Honda Nighthawk. Kawasaki Zephyrs and Suzuki VX800 and GS500E all springing from drawing boards.

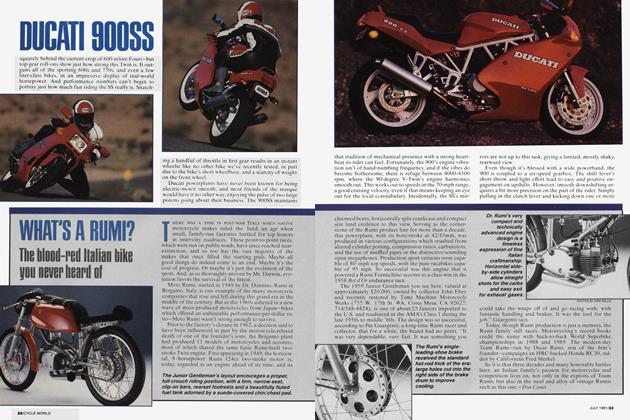

Still, the bike that many of those enthusiasts wanted to see return was the big-bore Suzuki GS—not the sporty E or supersport ES models, but the shaft-driven G model-as offered during the late 1970s and early '80s in 850, 1000 and 1 lOOcc displacements.

Suzuki was listening, and the result is the bike you see here—the $5999 GSX I 100G. Though it bears a strong resemblance to the much-vaunted GSI 150E—the last of the GS line in 1985 —the GSX is more like what the GSI 100G would have grown into had it not been discontinued in 1 983. And though it features a low-tech tubularsteel frame, the GSX is not merely a warmed-over version of a 10-year-old design; instead, it's the first GS ever to mate multi-valve engine technology with rising-rate, single-shock rear suspension and shaft drive.

It is that engine which is the most impressive component of the GSX 1 100G. Essentially the same pow'erplant employed by the repli-racer GSX-R 1 100. the GSX motor has a few significant differences. Most notable is the addition of a secondary balancer shaft, driven off a gear adjacent to the number-two cylinder’s crankshaft counterweight, which transforms the air-and-oil-cooled, 1127cc, dohc inline-Four from a buzzing beast of a motor to a veritable purring kitten. The counterbalancer is adjustable by removing the oil sump, but this isn't a maintenance requirement; it exists solely to set gear backlash in the event of an engine rebuild.

Also different is the GSX's valvetrain: Rather than employing individual rocker arms and shim adjustment as found on 1991 GSX-Rs, the GSX uses the screw-type valve adjusters and forked rocker arms of pre-'91 models. The GSX's cams are different as well, offering less lift on both the intake and exhaust sides, and less overlap than the GSX-R's for increased low-end grunt.

None of these differences are obvious from the outside of the engine, but what is noticeable are the G’s shaftdrive fittings. Suzuki engineers redesigned the GSX-R's engine cases to accept the shaft, and a secondary reduction system now' bolts directly to the cases. Interestingly, the secondary is lubed by engine oil. rather than by gear oil as on most other shaft-drive systems. The driveshaft itself is essentially the same piece used on Suzuki’s discontinued Cavalcade tourer, and is lubed by gear oil in the traditional manner.

Suzuki also fitted the GSX with a wider-ratio transmission than that of the GSX-R, w ith a lower first and taller fifth gear, in the interest of easier acceleration from a standstill and lower rpm at cruising speeds.

Other than these differences, the engines are for the most part mechanically identical. Ignition timing has been altered, as has jetting on the bank of four 36mm Mikuni semi-flat-slide “Slingshot" carburetors, which are the same type as those used on the GSX-R. The carbs breathe through an under-tank airbox, and are fed by an electricfuel pump, a requirement due to the low positioning of the petcock. As on the GSX-R. the G's carburetor float bowls vent to the airbox, rather than to the atmosphere, which limits fluctuations in air density that would be brought on by turbulent air passing by the vent hoses. This eliminates the flat spot that plagued carburetion of earlier GSX-Rs.

Swinging a leg over the GSX, the first thing you’ll notice is the cushy seat, this in keeping with the tradition set by the original GS850 saddle; those who remember the GS850 as having the best-ever motorcycle seat may have a newfavorite in the GSX. Next, you'll notice the high, wide, 1-inch-diameter buckhorn handlebar, which would look more at home on a Harley, but which feels fine on the Suzuki, fhe large-diameter grips are covered in soft, spongy rubber, which together with the chromed bar-end weights, rubber-mounted handlebar and rubber-covered footpegs help to further isolate the rider from vibration. Switchgear is old-fashioned, with the turnsignal switch a non-push-to-cancel item, and the angle of the horn button backwards from what we're used to, making it slightly cumbersome to use.

The motor fires with a simple touch of the starter button. and the dash-mounted choke knob can be backed off almost immediately. However, there's a flat spot between 3500 and 4000 rpm that doesn't go away until the engine is thoroughly warmed up. so it's best to wait a few minutes before riding away. Once it's warm, only a slight stumble off idle prevents the GSX's carburetion from earning perfect marks.

The G's transmission clicks smoothly into first gear, but once underway, the short throw of the bike's hydraulically actuated diaphragm-spring clutch and a bit of driveline slop conspire to make smooth gearchanges a bit tricky. Less-than-careful modulation of the clutch and throttle can cause the bevel-gear teeth in the driveshaft to slam together, making for unpleasant noises. Once you've learned to exercise the proper care, you probably won't have any complaints.

Turning the throttle also produces shaft-drive effect. the rear suspension extending under acceleration and compressing under deceleration, most notably in the lower gears. This can be a problem mid-corner, as suddenly backing-off the throttle causes the bike to squat, reducing available ground clearance with predictable results. This is something the GSX does not need, as its ground clearance is already limited during hard cornering. The centerstand touches down first, followed by the footpegs and the chromed covers that hide the collectors for the 4-into-2 exhaust system.

G3x1100G

As its conservative rake/trail figures (32 degrees/6.1 inches) and train-like 63-inch wheelbase would suggest, the GSX is rock-steady in a straight line. Steering is decidedly slow, though lighter than you’d imagine, thanks to the leverage afforded by its wide handlebar. The bar can’t erase the GSX’s weight, though, and at 620 pounds wet, it’s a real behemoth. This is most noticeable while maneuvering the bike in a garage or parking lot, where it feels distinctly top-heavy. It’s also a bit more difficult to coax onto its centerstand than most other bikes. After unloading the GSX from the Cycle World box-van. Shop Foreman Pat Tracy nicknamed the GSX the “Air-and-Oil Buffalo,” a variation of the old Suzuki GT750’s “Water Buffalo” moniker.

Once up to speed, however, the GSX does a fair job of hiding its weight. It's surprisingly flickable, and its doublebackbone frame is extremely rigid. A good rider can make time down a twisty road, provided he keeps the GSX's limitations in mind.

Unfortunately, it is those limitations which most disappointed us. Simply put. the GSX suffers from poorly chosen fork-spring rates. The bike loses half its available fork travel under its own weight, and more than that with a rider (or two) aboard. Even moderate braking will bottom the GSX's fork, and heavy braking across a rippled surface will seriously open your eyes.

Fortunately, the single rear shock is fully adjustable. with four clicks of compression damping, 20 clicks of rebound damping and a seven-position spring-preload collar. Cranking the spring-preload up improved ground clearance, but it then surpassed the shock’s rebounddamping capabilities.

Given the suspension's limitations, we were never able to dial in the ride to our satisfaction. The bike felt best wath its shock set to match its fork—that is, limp—where it offered an extremely plush ride around town and on the freeway. Not surprisingly, this w'as Suzuki’s intention, its target audience being the mature rider who sees little backroad action. If you buy a GSX primarily for commuting and light touring, you won’t mind the ride; if you plan to go fast, carry a passenger or add any of Suzuki’s many accessories for the GSX, some fork fiddling will be necessary.

In an attempt to improve the soft front end, we replaced the stock 7-and-l 1/16ths-inch spring-preload spacers with ones made of PVC tubing measuring 8-and-7/l 6ths-inch. This gave us a better ride height, improved fore-aft suspension balance and upped cornering clearance somewhat, but the spring rate w'as still too soft. We’d recommend replacing the springs w'ith aftermarket components when they become available.

Despite its size and weight, the GSX is fast. During our performance testing, it turned the quarter-mile in 1 1.32 seconds at 1 1 8 mph, and then showed a top speed of 1 36 mph on the radar gun—pretty respectable numbers for a standard-style bike lacking any form of aerodynamic bodywork. Acceleration from low speeds and top-gear roll-ons are its forte, however, as it proved to be a bit quicker than the Suzuki Katana 1 100 up to 60 mph, and virtually equal in roll-ons. Its lunge from a standing start is impressive; overzealous use of the throttle will cause the bike to wheelie spectacularly or to light up the rear tire. Those tires, incidentally, are bias-ply Dunlops, an 1 8-inch front and 17-inch rear.

Thankfully, the GSX’s pair of dual-piston front disc brakes are well up to the task of slowing it down. The single opposed-piston rear brake, however, is a bit unpredictable; it locks too easily, causing the rear end to hop up and dow n. Downshifting into low' gear at too high a speed results in a similar scenario.

Gsx1100G

Though the GSX never threatened to strand us, we did have a few minor problems with it during our testing. First, the inspection plate at the secondary-driveshaft juncture came adrift when the hoseclamp securing it came loose. Then, the petcock knob fell off. Both of these problems were easily repaired, however, and did not resurface.

If we seem less than over-the-moon in love with the GSX l 100G, that may be because we set our expectations too high. We loved the last Suzuki GS we tested, the l 985 115ÖE, calling it “the fastest, most-powerful standard ever built” and “probably the best performance-per-dollar bargain.” Considering that six years have gone by, we were expecting more of the same trom the GSX in an updated package—in other words, a new standard in standard-style motorcycles.

We didn't get it. What we got was an accurate replica of the old GSI 100G. assembled from contemporary components. If this w'ere I 985, we'd be impressed. But it's not, and we're a trifle disappointed.

Nevertheless, those looking for a good, all-around motorcycle-make that, musclebike—would do well to give the GSX l 100G their attention. And those looking to replace their much-loved GS l l OOGs at ter a decade of faithful service won't And a better choice. gg

SUZUKI GSX1100G

SPECIFICATIONS

$5999

American Suzuki Motor Corp.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue