GOING IN CIRCLES

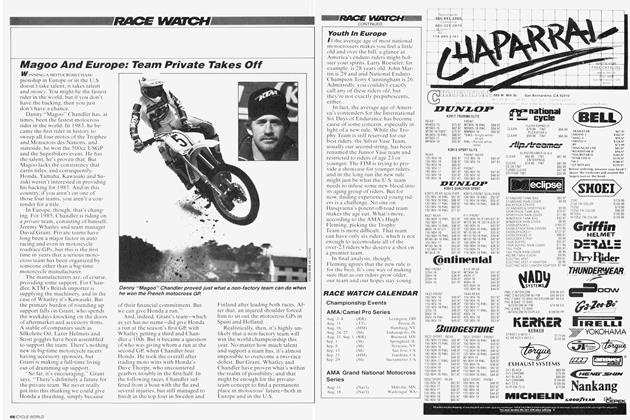

RACE WATCH

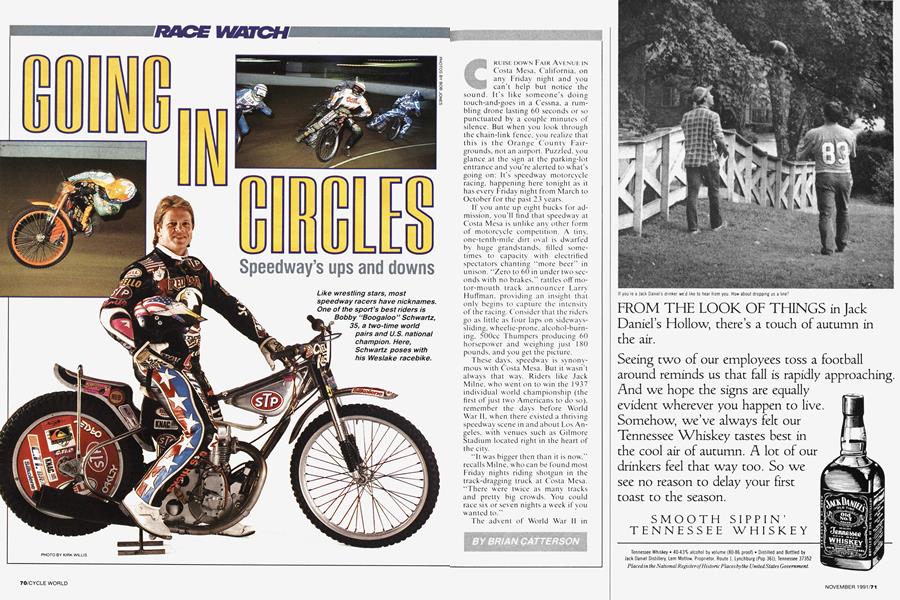

Speedway's ups and downs

CRUISE DOWN FAIR AVENUE IN Costa Mesa, California, on any Friday night and you can't help but notice the sound. It's like someone's doing touch-and-goes in a Cessna, a rumbling drone lasting 60 seconds or so punctuated by a couple minutes of silence. But when you look through the chain-link fence, you realize that this is the Orange County Fairgrounds, not an airport. Puzzled, you glance at the sign at the parking-lot entrance and you're alerted to what's going on: It's speedway motorcycle racing, happening here tonight as it has every Friday night from March to October for the past 23 years.

If you ante up eight bucks for admission. you'll lind that speedway at Costa Mesa is unlike any other form of motorcycle competition. A tiny, one-tenth-mile dirt oval is dwarfed by huge grandstands, tilled sometimes to capacity with electrified spectators chanting “more beer" in unison. “Zero to 60 in under two seconds with no brakes." rattles off motor-mouth track announcer Larry Huffman, providing an insight that only begins to capture the intensity of the racing. Consider that the riders go as little as four laps on sidewayssliding. wheelie-prone. alcohol-burning. 500cc Thumpers producing 60 horsepower and weighing just 180 pounds, and you get the picture.

These days, speedway is synonymous with Costa Mesa. But it wasn't always that way. Riders like Jack Milne, who went on to win the 1937 individual world championship (the first of just two Americans to do so), remember the days before World War II, when there existed a thriving speedway scene in and about Los Angeles, with venues such as Gilmore Stadium located right in the heart of' the city.

“It was bigger then than it is now," recalls Milne, who can be found most Friday nights riding shotgun in the track-dragging truck at Costa Mesa. “There were twice as many tracks and pretty big crowds. You could race six or seven nights a week if you wanted to."

The advent of World War II in 1941 curtailed the action briefly. And though speedway racing resumed in 1 946. another development soon forced it into hibernation.

BRAIN CATTERSON

“All racing stopped when television was invented,” Milne says. “People just stopped going to the races. Everyone was home watching TV.”

It wasn’t until 1968 that speedway reemerged in Southern California, and Milne played a part in that by hiring Harry Oxley to work in his Pasadena motorcycle shop. A dirttracker at heart, Oxley’s attention was soon captured by the Jawa speedway bikes on the shop’s sales floor and by the memorabilia on its walls.

A year later, Oxley began promoting speedway races at Costa Mesa, and he’s done so ever since.

Racing there began on an amateur level, but it soon progressed to professional status because, as Oxley explains, “We started drawing spectators almost immediately." Other tracks were added to create a weekly circuit, and before long, some of the riders were making a pretty comfortable living.

“ln I 974. it took off big," Oxley continues. “We sold 10,000 tickets that year for the National."

Today, Oxley is considered the> godfather of Southern California speedway. But his is not the only show in town; there are three other tracks that make up the weekly schedule. Wednesday finds the riders at Glen Helen, Thursday they’re at Lake Perris and Saturday they’re at Victorville. A host of others have come and gone over the years; Oxley says that when he stopped counting 10 years ago, there were I 4 tracks in Southern California, not to mention those in Northern California, upstate New York and Ohio.

As speedway's popularity rose, so did the level of competition. Thus, some of the top riders began leaving for Europe, hoping to bring home a world championship. The most successful of these was Bruce Penhall, who won two consecutive individual world championships in 1981 and '82. But there was another reason for going overseas: money. The thriving British League offers not only a chance to face the best riders in the world on a regular basis, but to earn higher salaries.

To do that, U.S. riders must adapt to the European tracks, which are typically longer and faster than those in America—and more dangerous. Racing here is far safer. Given the closeness of the races, crashes often involve two or more riders, and can look horrendous—bikes and riders have been known to launch over or> even through the erashwall—but serious injuries are rare. Only one rider has ever been killed on the Southern California speedway circuit.

One facet of speedway racing that is unique is its method of determining champions: Despite the fact that the SoCal riders race four nights a week, the points they earn don't count toward the national championship—they only serve to qualify riders for the National, which is a onenight. winner-take-all proposition held as the Costa Mesa season finale.

Over the years, speedway motorcycles have remained more or less unchanged. The modern-day bikes are based on—and not unlike—the British-built JABs raced by Milne and his peers 60 years ago. They’re all powered by high-compression, single-cylinder four-strokes running on methanol, contained in lightweight, rigid (no rear suspension) frames, with forks boasting a mere 1.5 inches of undamped travel. Narrow. 23-inch front wheels are paired with only slighter wider. 19-inch w heels at the rear. To keep costs down, a rule man-> dates that rear tires sell for under $30, and a rider can use only one new rear tire per night. The most common brand is Kenda. made in Taiwan.

There are four brands of speedway bikes available today. The British built Weslake is the most popular. with the British Godden. Italian GM and (`zechoslovakian Jawa also corn petitive. All have four valves, though the Weslakes are activated by pushrods and the others are sohc. At one point, steel-shoe guru and speed way fanatic Ken Maely made and sold his own motors, to which the current Godden and GM bear a striking resemblance.

As in other forms of motorcycle racing, riders are grouped according to skill levels. In speedway, these are called divisions: First division is for Experts, second division is for Intermediates and third division is for Novices. A Junior speedway program is run on a bi-weekly basis, with riders as young as 7 years old on scaleddown, 250cc machines powered by everything from trick Weslakes to Honda XRs and Triumph C ub engines. Alternating with the Juniors is a sidecar program, with low-slung three-wheelers powered by lOOOcc Twins and Multis.

Speedway rules are as unique as the machines. First, there’s no touching the starting tapes, which rise straight up to begin a race. If your front wheel contacts the tapes, you’re excluded, and a reserve rider is sent in to replace you. Second, if you cause an accident, you’re excluded— unless it involves half the field on the first lap, in which case you get another chance. If you’re involved in an accident and are eligible for the re-> start, but your equipment needs repairs, you have two minutes to set things right. Surpass that time, and you're excluded. There are no excuses and no apologies. And never, ever, any arguing with the referee. Do so and you’ll be fined or suspended.

Perhaps most unusual of all, there is no practice. Your first race of the night provides your first opportunity to ride, and if you don't transfer, it can also be your last.

Principally, there are two types of race formats: scratch and handicap. Scratch racing is the traditional European type of racing, and consists of four riders, all starting at the tapes, going four laps. In America, scratch races are run like any other dirt-track event, with heats, semis and a final.

In Europe (and at special events in the U.S.), a round-robin format is used in which each of the 16 riders meets each of his competitors once, and the winner is determined by points.

Handicap racing isunique to America, and consists of eight riders going eight laps, with the most-experienced riders starting from the 50yard line, the least-experienced on the tapes, and the others staggered in between.

Which format do the top riders prefer? Almost universally, they like scratch racing. “Handicap racing is just a lottery,” says two-time National Champion Bobby Schwartz. “Track conditions are slicker now, which makes racing safer, but it’s > harder to pass.”

“The track surfaces are too slick and too flat.” concurs Phil Collins, a British transplant now racing in the States. “1 can pass the other riders around the outside if there’s enough of a cushion ora banking, but with no dirt or an adverse camber, it's impossible.”

Handicap racing, though, provides a good money-making opportunity for the top riders because a rider who wins coming from the rear earns more money than one coming from the front.

Money. That's a touchy subject these days. With the economy in a slump, attendance has been the lowest in years. Oxley blames it on the ailing motorcycle industry: his daughter Laurie, who works in the front office, says it's because beer prices have gone up. Whatever the reason, with the purse based on a percentage of ticket sales, the riders are earning less money. This has forced many to take on jobs, and some, like 21-year veteran and 1985 National Champion Alan Christian, to contemplate retirement.

“I'm moving back to Reno at the end of the year,” Christian says. “I was making a pretty good living, but I lost my STF sponsorship, the crowds are down and there's no pay, so my interest is waning.”

Schwartz elaborates: “You can still make $35,000 a year racin». but now it costs $20.000 to do it. My accountant says it's a hobby.”

“We're having trouble getting the young people to come to the races,” admits Oxley. To do this, promoters have tried everything from bikini contests to Fox Nights (ladies admitted free) to daredevil shows to buyone-get-one-free ticket deals. And there's an attempt to recapture the old fans who have been absent lately. “They're all still here, it's just a matter of promotion.” Oxley says.

Part of the problem may be that, as in roadracing, the top riders all head for Europe at their first opportunity, leaving the American fans with fewer recognizable names. More top-level> riders are needed, and with the Junior program constantly jeopardized by insurance hassles, promoters are being forced to look elsewhere for new blood. By the time this issue hits the newsstands, the first of a number of low-cost riding schools will have been held at Glen Helen, aimed at

attracting would-be speedway racers—perhaps even some ex-Pro motocrossers—to the sport.

What’s ironic is that speedway is getting more attention than ever. “Speedway America,” a one-hour television show hosted by Huffman and Pen hall, airs for 1 3 weeks on the Prime Ticket cable network. And a weekly AM radio show broadcasts the races live.

It's an unusual scenario, spectator attendance dropping as media interest rises. Are people staying home, choosing to watch the races on TV or to listen to them on the radio? Whatever’s happening, Penhall, for one, believes the situation will improve.

“Speedway has gone through its peaks and valleys,” he says. “It’s in a valley now, but it'll turn around. It

always does.” E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

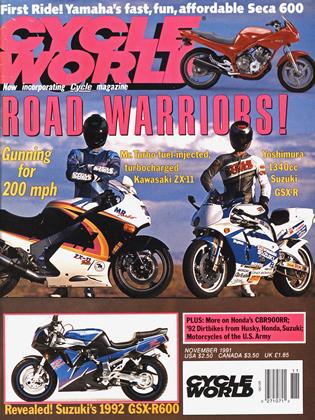

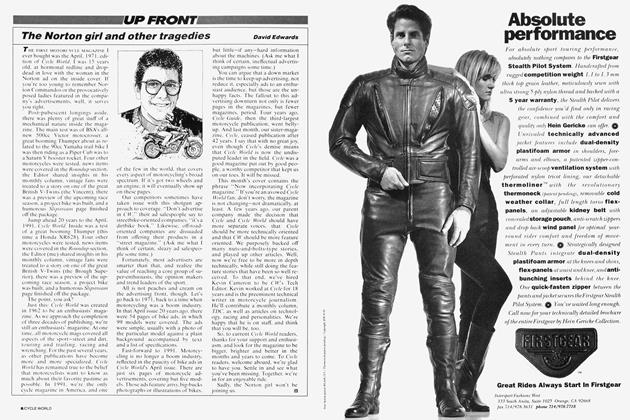

Up Front

Up FrontThe Norton Girl And Other Tragedies

November 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeNone Dare Call It Progress

November 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsReplacements

November 1991 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCUpheavals

November 1991 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1991 -

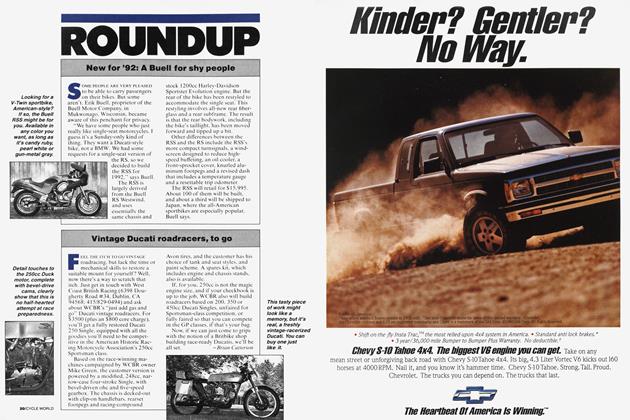

Roundup

RoundupNew For '92: A Buell For Shy People

November 1991