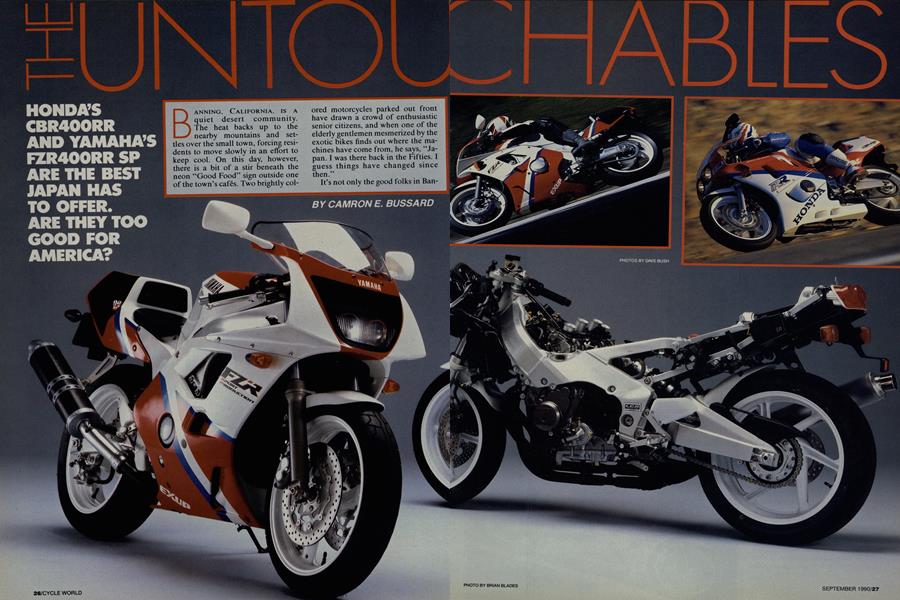

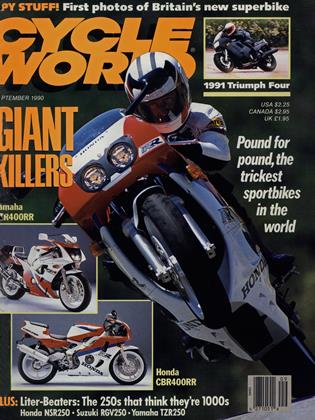

THE UNTOU CHABLES

HONDA'S CBR400RR AND YAMAHA'S FZR400RR SP ARE THE BEST JAPAN HAS TO OFFER. ARE THEY TOO GOOD FOR AMERICA?

BANNING, CALIFORNIA, IS A quiet desert community. The heat backs up to the nearby mountains and settles over the small town, forcing residents to move slowly in an effort to keep cool. On this day, however, there is a bit of a stir beneath the neon “Good Food” sign outside one of the town’s cafés. Two brightly colored motorcycles parked out front have drawn a crowd of enthusiastic senior citizens, and when one of the elderly gentlemen mesmerized by the exotic bikes finds out where the machines have come from, he says, “Japan. I was there back in the Fifties. I guess things have changed since then.”

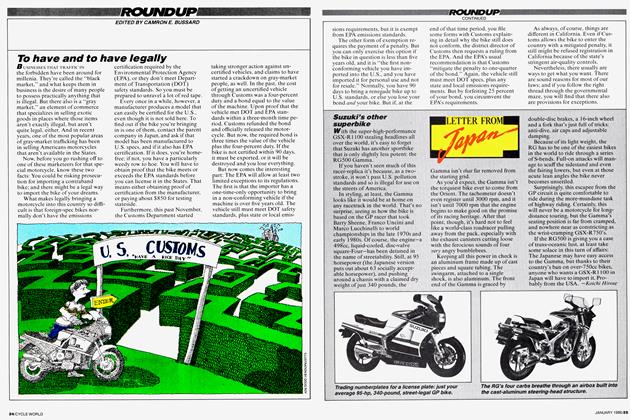

It’s not only the good folks in Banning who have never seen motorcycles such as these, the Honda CBR400RR and the Yamaha FZR400RR SP, a pair of twowheelers so advanced they seem to have taken direct strikes by bolts of technological lightning. In fact, only a handful of people in this country even know these incredible bikes— built for the Japanese domestic market—exist. While they are for sale like so many fruits and vegetables in Japan, here, they are as rare as a cool summer’s day in the Mojave. And just as desirable. That description could also apply to the CBR, which matches the FZR corner for corner. Visually, though, the CBR’s unusual frame stands it apart from the Yamaha. Breaking away from current frame-design trends, which mate steering heads and swingarm-pivot castings via large, flat, outwardly curved aluminum beams, the CBR’s frame uses abbreviated beams that tie into a convoluted casting that runs from the swingarm pivot almost to the carburetor float bowls, where it then wraps around the rear of the cylinders to bond with the twin spars. Viewed from the side, the CBR’s frame resembles an “S.” The Yamaha’s 399cc, liquidcooled inline-Four has as impressive an engine spec chart, but the FZR comes equipped with an EXUP exhaust-control system, intended to boost low and mid-range power. That is just where the Yamaha needs a shove, because it comes with a relatively tall first gear and is a little difficult to get off the line. But once moving with the revs climbing above 5000 rpm, the FZR begins to sing. Unfortunately, our test bike’s rhapsody was cut short, as it would not rev cleanly beyond the 12,500-rpm mark, effectively eliminating the topend thrust that makes these bikes so much fun to wring out. Because the FZR ran strongly everywhere else, we suspect that an electronic method of limiting horsepower is the culprit. As of presstime, FAXed inquiries to Japan remained unanswered, but the conjecture is that this allows the street version to produce no more than the stipulated 59 horsepower, and that the addition of a “race use only’’ black-box will most likely cure the problem.

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

It is the 400cc sportbike class, in conjunction with the 250cc twostroke class, that represents the cutting edge in the Big Four’s ongoing battle of one-upmanship, a clash that has taken them into the realm of expensive metals and state-of-the-art engineering just to stay even with the competition. The class, of which the CBR and the FZR are just two examples, is a hotbed of activity in Japan partly because of a licensing system that makes bikes of 400cc and below much easier and less-expensive to get permits for than larger-displacement machines.

Further, because of rules for production racing in the popular F-3 class (for 400cc four-strokes and 250cc two-strokes), the bikes have become showcases for the manufactures to exhibit some of the most-sophisticated and technologically advanced motorcycles possible. The old NASCAR adage, “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday,’’ applies just as well in Nagoya as it does in Nashville.

That motorcycles of this caliber exist is reason enough for anyoneZ

even remotely curious about bikes to be interested, but for American riders, there is additional incentive to pay close attention to what goes on in the Japanese 400 class. Historically, the 600cc sportbikes we ride here grow directly from the 400s there. The original Honda Hurricane 600 was a 400, the Kawasaki Ninja 600 was first a 400 and the FZR400 was the precursor to our FZR600.

One trend that could come our way soon is exhibited by the CBR. For the past few years, performance with economy has been the philosophy behind Honda’s Hurricane/CBR line of sportbikes, at least the ones we’ve seen, which have had steel frames and roughly finished (albeit totally hidden) engines. And while the performance-with-economy routine still plays well in America and Europe, it no longer fills dealerships in Japan with enthusiastic buyers. There, that whole concept has been scrapped in the heat of the performance wars that define the 400cc sportbike class. Thus, Honda has the CBR400RR, pound for pound one of the mostperformance-intensive motorcycles in the world.

Of course, the CBR had to be up to snuff to compete with bikes like the FZR400RR SP (for Sport Production), arguably the most-hardcore sportbike ever to turn a sticky radial tire. The SP is essentially a 400cc version of Yamaha’s potent, 750cc OWOl, and it shares little with the ordinary FZR400 that we get in the U.S. Its aluminum Deltabox frame, carbon-fiber exhaust canister and blacked-out numberplates point the bike in the direction of the track, but its turnsignals, mirrors and horn make it legal on the highway.

Those few concessions to the demands of the street take little away from the real mission of the FZR, which is to explore the highest cornering speeds possible, aided by its taut, multi-adjustable suspension. Few, if any, motorcycles made can outhandle the FZR: It is small, agile and remarkably stable, given that it changes direction with almost no effort whatsoever.

While this certainly is an unorthodox-looking frame, it’s beautifully crafted, with gorgeous welds and intriguing pieces, including the “Gull Arm” swingarm, which is curved upward on the right side in the latest GP fashion, to allow the exhaust pipe to be tucked up out of the way. Honda has, however, stocked the CBR with conventional front suspension, even though some others in the class have now turned to upside-down forks.

But even though at rest the CBR’s suspension feels as soft as warm butter, once rolling, even at high speeds, it remains as supple and compliant as you could ask for, with no wallowing in corners. And getting the CBR into a corner is almost like steering by thought, because it takes such a light touch to initiate a turn. Once in the corner, the bike remains neutral—so much so that you could almost remove your hands from the bars and the bike would continue unaffected. In terms of a balance between highspeed stability and cornering prowess, the CBR ranks right up with the FZR as one of the all-time best-handling production motorcycles.

Both machines, as with all 400cc motorcycles in Japan, are restricted to 59 horsepower, but no one said that all horsepower is created equal. The CBR is propelled by a liquidcooled, 399cc, inline-Four derived directly from the 1986 Hurricane 400, and seen in the U.S. on the likable CB-1. To compete with the other high-performance 400s, the latest edition CBR has new CV carburetors breathing through an airbox that takes its air supply through openings in the frame. Straighter intake ports, new three-ring pistons with side cutaways, and reshaped combustion chambers are other changes, though the engine still has its bank of cylinders canted forward at 35 degrees.

The Honda had no such governor, eagerly zinging its tach needle to redline. its engine quiet and deceptively smooth both in power delivery and in regards to vibration. In testing, the CBR ripped past our radar gun at 1 29 miles per hour (the strangled FZR could only manage 111), and knocked off a 12.1-second quartermile time. Some perspective is in order here. Remember the awesome Honda 750 Four, the bike that set the motorcycle world on its ear in 1 969? That bike topped out at 123 miles per hour and managed a 13.38-second run at the dragstrip. How about the 1973 Z-1, the 900cc streaker that CW once called “one of the two or three quickest road bikes in production”? Top speed. 120; quarter-mile time, 12.6 1 seconds.

There is never a point where the Honda suddenly produces an instant blast of power; it pulls from just off idle, picks up momentum around 4000 rpm, and then really boils between 7000 and the 14.000-rpm redline. But the CBR loves the higher

reaches of its rev band, and for really making time on a backroad, it has to be kept spinning in five-figures.

As the photographs show, both machines have styling and workmanship that are a match for their performance. On the CBR, with the exception of the plastic air ducts located beneath the fuel-tank, every piece looks handcrafted. The brushedaluminum exhaust canister, for example, has a one-off look, with unbelievably beautiful welds. And the FZR looks like it just rolled out of the factory race shop.

The main difference between these two remarkable machines is that the CBR is the more-comfortable, more-streetable, motorcycle. Though both are small, the CBR doesn't have to be ridden like a racebike to be enjoyed, while the Yamaha is a precise instrument intended for a specific duty. It's impossible to claim that one or the other is the better motorcycle; it’s more accurate just to say that they are different and that the Honda has a muchbroader intention than the Yamaha.

Of course, there is a price to pay for the beauty and function of these machines: In Japan, the CBR costs $4820 and the FZR’s price tag reads $5786. For the manufacturers to bring them to the U.S., add anywhere from $800 to $1000 more, which would price these 400s higher than the bigger, faster, quicker 600s we already get, guaranteeing almost-certain showroom death for the smaller motorcycles, no matter how trick they might be.

Rather than dismiss them as expensive and unobtainable 400s, though, we prefer to think of the CBR and the FZR as two of the finest production motorcycles we’ve ever ridden, the only pity being that there’s not a place for them in the USA. m

Honda CBR400RR

$4820

Yamaha FZR400RR

$5786

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontFathers, Sons And Motorcycles

SEPTEMBER 1990 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeOut In the Midday Sun

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Discriminating Cheapskate

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersDinin' Dressers

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupConquest Goes Polish

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

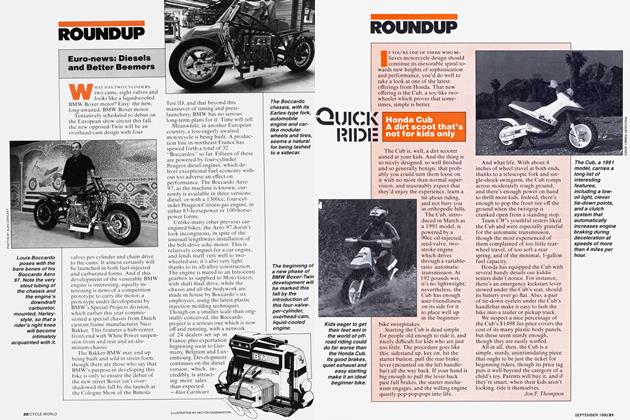

Euro-News: Diesels And Better Beemers

SEPTEMBER 1990