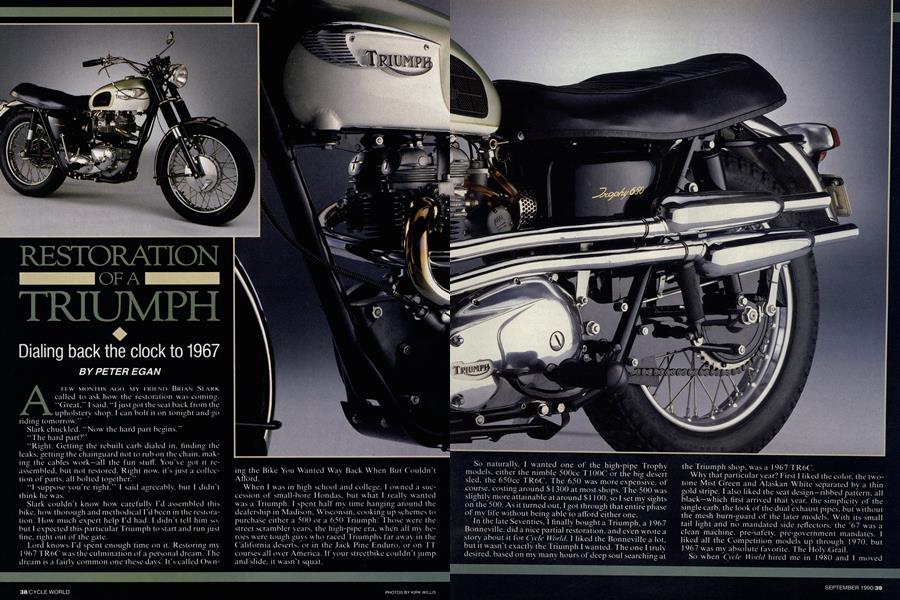

RESTORATION OF A TRIUMPH

Dialing back the clock to 1967

PETER EGAN

A FEW MONTHS AGO, MY FRIEND BRIAN SLARK called to ask how the restoration was coming. "Great," I said. "I just got the seat back from the upholstery shop. I can bolt it on tonight and go riding tomorrow." Slark chuckled. "Now the hard part begins." "The hard part?" "Right. Getting the rebuilt carb dialed in. finding the leaks, getting the chainguard not to rub on the chain, making the cables work—all the fun stuff. You've got it reassembled. but not restored. Right now. it's just a collection of parts. all bolted together. "I suppose you re right" I said agreeably. but I didn't think he was.

Slark couldn't know how carefully I'd assembled this bike, how thorough and methodical I’d been in the restoration. How much expert help I'd had. I didn't tell him so. but I expected this particular Triumph to start and run just fine, right out of the gate.

Lord knows I'd spent enough time on it. Restoring my 1967 TR6C was the culmination of a personal dream. The dream is a fairly common one these days. It's called Ownin~ the Bike Y~u Wanted Way Back When But (`ouldn't Afford. \Vhen I was in hi~h school and colle~e. I owned a succession of small-bore I londas. hut what I really wanted

was a Triumph. 1 spent half my time hanging around the dealership in Madison, Wisconsin, cooking up schemes to purchase either a 500 or a 650 Triumph. Those were the street scrambler years, the high-pipe era. when all my heroes were tough guys who raced Triumphs far away in the California deserts, or in the Jack Pine Enduro, or on TT courses all over America. If your streetbike couldn't jump and slide, it wasn't squat. but it wasn't exactly the Triumph I wanted. The one I truly desired, based on my many hours of deep soul searching at the Triumph shop, was a 1 967 TR6C. tone Mist Green and Alaskan White separated by a thin gold stripe. I also liked the seat design—ribbed pattern, all black—which first arrived that year, the simplicity of the single carb. the look of the dual exhaust pipes, but without the mesh burn-guard of the later models. With its small West, I sold the Bonneville. I'd surely find a Trophy TR6C in California, and when I did. I'd do it up right. Fortunately, two books saved my hide. One was the indispensable Triumph Twin Restoration by Roy Bacon, which has hundreds of clear, close-up photos and a lot of good advice. The other was a Xerox reproduction of the '67 Triumph parts book, supplied to me by Bill Getty at JRC Engineering. I also bought most of my Triumph parts from Bill, and he was kind enough to give me needed technical advice each of the hundred or so times I called to place an order. Still, my own photos and drawings would have been a big help. Another whole Triumph standing by for reference would have been even better. With the chassis rolling, I dropped it off at Time Machine, and Denny bolted the rebuilt engine into its new cradle, hooked up the electrics and started the engine. The crowning touches were the gas tank, sidecover and oil tank. I decided not to try painting these myself (being a somewhat unsteady pinstriper) and had them painted by a local shop called Color Cycle. They charged $350 and did a beautiful job, with a clear coat over decals and tank paint. Aside from those few shortcomings, nearly all the painted and plated surfaces are now appropriately shiny, and virtually every surface that rubs on any other surface is now new—bearings, chains, sprockets, swingarm bushings, forks, shocks, tires, cables, brakes, ignition points. There is a price to pay for this compulsiveness, of course. Spread over two years of work, the cost of restoring my Triumph came to just over $5000, including the original cost of the bike.

tail light and no mandated side reflectors, the '67 was a clean machine, pre-safety, pre-government mandates. I liked all the Competition models up through 1970. but 1967 was my absolute favorite. The Holy.Grail. So naturally. I wanted one of the high-pipe Trophy Why that particular year? First I liked the color, the two-

models, either the nimble 500ce T100C or the big desert sled, the 650cc TR6C. The 650 was more expensive, of course, costing around $ 1 300 at most shops. The 500 was slightly more attainable at around $ 1 100, so I set my sights on the 500. As it turned out, I got through that entire phase of my life without being able to afford either one. So when Cycle World hired me in 1980 and I moved In the late Seventies.! finally bought a Triumph, a 1 967 Bonneville, did a nice partial restoration, and even wrote a story about it for Cycle World. I liked the Bonneville a lot,

I discovered when I got here that most of the Sixties Trophies had, indeed, gone to the desert. Their owners had sawed off the fenders, thrown the original pipes and mufflers away, tossed the headlights, padded the seats, installed dual-carb Bonneville heads, raked the steering heads, dented the tanks and generally thrashed the poor bikes to death. (Which I suppose is what they were built for, after all.) Street-legal, original Trophies were in short supply here. I looked for a long time and didn’t find one. Until two years ago.

I saw an ad for a 1967 TR6C in the paper, “All stock, beautiful shape, 1 300 original miles, 2nd owner. $ 1 350.”

I left work, drove straight to the man’s house and bought the bike. It was all there, but a little loose mechanically.

The tank had been repainted solid green, the knee pads were gone, the seat had a small tear, the fork leaked and the sprockets were worn. It started and ran fine, but there was a strange, intermittent upper-end clatter that I thought might be a broken valve spring. I rode the bike for a year before I got the courage to deny myself its daily use and take it apart.

As mentioned in a previous CW column, I tried first to restore the bike in small increments, just to keep it on the road. Wheels came off first, one at a time. I had the hubs powder-coated and the wheels respoked in stainless steel, and then installed new tubes and new Dunlop K70 tires. made-in-Japan modern replicas of the originals. I installed new wheel bearings and a new' rear sprocket and chain, had the brake drums turned, new shoes skimmed for a concentric fit, the hub cover rechromed and the brake backing plate polished. Total cost, of just this wheel-related restoration, came to about $675.

New primary drive came next—clutch basket, plates, primary chain, adjuster, tensioner and sprocket. This set me back two weekends and $200 for parts.

Suspension next, and this is the step that finally took the bike off the road. Triple clamps and rust-pitted fork came off. and new chrome fork tubes were ordered from Franks, at $100 each. Then I went to work removing the engine and disassembling the bike down to the last nut and bolt. I sent out all bolts and screws for plating in white cadmium and then began what I will always remember as the Summer of Endless Beadblasting.

Two friends, Chuck Johnston and Richard Straman, both had industrial-size beadblasting cabinets and allowed me to spend many hours, using up their compressed air while blasting swingarm, shock covers, fender braces, footrests and the nine or 10 thousand small bits of hardware and mounting plates that all hold a Triumph, sandwich-like, together. The main frame section was too big for a beadblaster, so I sandblasted it outdoors.

With all the frame parts clean as bleached bones, I had to decide what finish to use for the black frame parts. Powdercoat? Not pure and original, some said. Looks too plastic. Use paint. Others said they wouldn’t use anything but powdercoat. This being my first true ground-up restoration, I decided to go with a combination and judge for myself. The main frame section and swingarm were powdercoated ($250) and all other parts I primered with zinc chromate and painted in black Imron. with the help of Chuck Johnston and his paint booth. Cost of paints, abrasives and solvents came to around $ 100.

Results? Both the Imron and powdercoat look fine. If it isn’t put on too thick, powdercoat doesn't have that sealed-in-plastic look that has given it a bad reputation, and it’s tough and doesn’t scratch easily, which is good when you are installing an engine. If I were to do it again, I’d powdercoat the whole frame and use Imron (as I did here) on parts like fork legs and shock covers, where a perfect, high-gloss finish is needed.

For the engine rebuild, I deferred to my friend Denny Berg, who runs a motorcycle shop called the Time Machine. Denny has years of experience building Triumph dirt-trackers and making them last, and he agreed to do the engine and gearbox for $1400, including new bearings, pistons, valves, guides, springs, etc., plus machine work, polishing and installation in the frame. During teardown, he discovered the source of the phantom head noise: a loose valve guide moving randomly with the valve. With 1300 miles on the engine, everything else was worn, but serviceable.

While Denny worked his magic on the engine, I started putting the frame back together and getting it up on its wheels. Here is where I discovered that the restoration books aren't kidding when they say to photograph and sketch everything before you take it apart. On the Triumph, some bolts have two washers, some have none, some go in from the left, some right, some use lock washers, some not, etc. With a photo or a drawing, you can assemble a section in about five minutes; relying on memory, you can spend two experimental hours on the same job. Then you later discover the four bolts you used on the axle caps belong on the handlebar clamps, and so on.

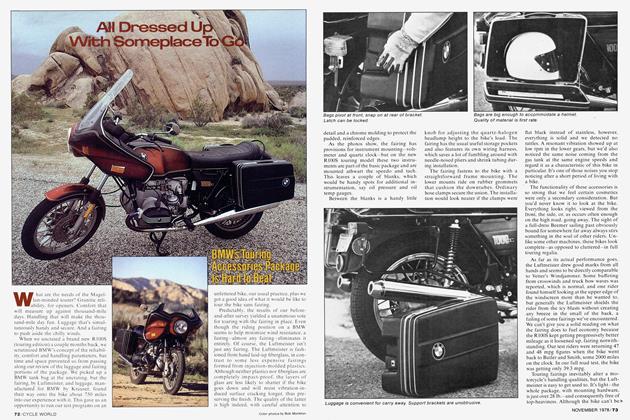

“Versatility Plus!” screamed the magazine ad for the 1967 TR6C, “A proven winner in enduros and cross-country events, yet ideal for on-the-road riding. ” So far, Egan’s restored Triumph Trophy 650 has yet to compete in an enduro, but it’s getting plenty of street use along with the occasional jaunt down a dirt road.

The seat was something of a problem. The old one was torn and crumbling, so I took it apart, beadblasted the pan, painted it with Krylon enamel and ordered a new cover and foam. The seatcover was backordered for several months from the supplier, and when it came it was a onestyle-fits-all version, shaped more like the plump mid-Seventies Bonneville seat than the flat, rakish Sixties version. So I had a local upholstery shop make a replica from the original, using the original top panel, which was not torn. Cost: $ l 50, plus $50 for foam.

My iast item to rebuild was the old Amal Monobloc carburetor (I’d been using a new Amal Concentric before the restoration). I beadblasted the Monobloc body and installed new jets, needles and slide, then cad-plated the fittings. Another $ 100, roughly. I bolted the carb on, fired up the engine and went for a ride.

Here's where Brian Slark’s admonition that a restoration is only a starting point began to come true.

During the first two months of riding, I fouled innumerable plugs (and walked many miles carrying a helmet and jacket) while trying to dial-in the jetting and needle height, and finding the ideal sparkplug heat range. Chronic weak spark from the old off-road, non-battery ET ignition system was part of the problem, and (being no electrical genius myself) I finally asked Denny Berg to install a 12-volt stator, new advance mechanism and Mity Max ignition box, which gives better spark and starting.

The bike is finally alive and well, and Eve now done several hundred miles in weekend rides and commutes to work.

So, how does it feel?

It feels like ... a Triumph. Light, narrow, agile, almost bicycle-like in its effortless sweep through corners; a balloon-tired Schwinn with a 650 engine slung low in the

frame. The sound is a pleasant combination of verticalTwin muttering snarl and light valve-train clatter. Brakes? Yes, but plan ahead. Power is moderate by current standards (original brochures say 45 bhp at 6500 rpm) but the bike is quick enough to be fun. I went up two teeth from stock on the countershaft sprocket, so highway cruising at 65 miles per hour is done at a fairly relaxed 3500 rpm.

Overall, the Triumph feels compact, solid and slightly antique, even compared with my Norton 850 Commando. It is a bike that reflects nicely the technology and expectations of its time, which included an admiration for light weight, graceful simplicity and a high state of finish in all the individual components, be they tank badges, choke levers or timing cases. Very Sixties, with strong hints of much-earlier roots. Which is exactly what I wanted. The original idea, after all, was to buiíd a brand-new 1967 Triumph—the one I never got to buy.

A fine goal, but is this one really brand new?

Yes and no. There are still things left to do. Like silk-screen the Triumph logo on the back of the seat. Also, the instruments are original and faded (and will be until I can find somebody who knows how to rebuild them), and I’ve left the original chrome on the pipes and mufflers, which have the slightly burnished, hazy quality of age. I guess, after all, I wanted the Triumph to be new in function without losing every link to its own past. A few reminders of the bike’s gathering antiquity seem worth leaving untouched, as long as it runs well.

etc. This is the core of a restoration. When you are out on the road, there is a place in the mind that wants to know that a machine is whole, that the pieces are working as they should and the noises you hear are all good ones. That the bike has life ahead of it as well as behind it.

When I first added it up, that sounded like a staggering amount of money to me, what with my notions of value lagging well behind inflation. The total made me shudder just to think about it. Then I began to rationalize. 1 made a trip to the library and found that, according to the Con-

sumer Price Index, a $1300 TR6C, if sold new today, would cost $4890 in 1 990 dollars. Turning that around, it seems I have paid the 1967 equivalent of $1329 to have myself, essentially, a brand-new Triumph.

Not such a bad deal, really. I think I'll just consider the extra $29 over list as a fair price for storage. Twenty-three years’ worth. My labor, of course, is always free. B3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontFathers, Sons And Motorcycles

SEPTEMBER 1990 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeOut In the Midday Sun

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Discriminating Cheapskate

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersDinin' Dressers

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupConquest Goes Polish

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

Euro-News: Diesels And Better Beemers

SEPTEMBER 1990