BIG TWINS

Exploring aboard the BMW R100GS and Honda Transalp

COMPROMISE IS ONE OF FIFE’S cornerstones, and when it is properly applied to motorcycles, it can be an especially good thing. The two motorcycles you see here, the BMW R1OOGS and the Honda Transalp, are evidence of that. By applying judicious bits of compromise, the designers of the Honda Transalp and of the BMW R1OOGS have honed these bikes into machines that specialize, if you will, in general use on both paved and unpaved roads.

“Roads” is the key word here. These may be dual-purpose bikes, but they’re dual-purpose bikes positioned at one end of the D-P spectrum, the end that's covered with asphalt, or at least well-graded. They can indeed be coaxed over some pretty rough trails, but they’re far more comfortable and secure, and far more fun. on maintained byways.

The Transalp, which with the disappearance this year of the NX650. is Honda's only big-bore dual-purpose motorcycle, is largely the same bike as it was when it was introduced here in 1989. Powered by a liquid-cooled V-Twin, the Transalp is, at 421 pounds dry, light for a streetbike, but heavy for a dirtbike.

The Beemeralso is, at 454 pounds, on the porky side of the dirtbike world. But like the Transalp, it’s light for a streetbike, and its weight, courtesy of its opposed-Twin engine, is mounted low in its chassis, so it not only feels lighter than the Honda, it feels lighter than it really is.

There’s another factor both bikes have in common, a factor which is one of the reasons both are far more at home on paved roads than on dirt paths. Though each uses a high, wide, dirt-style tubular handlebar, the seating position on both bikes is streetoriented. and the seats and fuel tanks on both force the pilot to stay much farther aft of the steering head than he would on a pure dirtbike. This is key, because it means the front wheels can't be loaded with the pilots’ body weight in corners. That means the front ends are quick to slide, so dirt corners are best taken slowly, with care. The BMW is especially treacherous, because its massive opposed cylinders not only make the bike tremendously wide, they also hamper a dirt rider’s instinctive reaction—putting his foot out when the bike starts to slide. Try it, and you'll get a shinfull of cylinder head.

In spite of the differences in engine size —the Honda's displaces 583cc, the BMW’s, 980cc—both provide similar performance. The Honda's V-Twin pushes the Transalp through the quarter-mile in 13.98 seconds at 93.16 miles per hour, while the Beemer Boxer does the quarter in 13.75 seconds at 96.67 miles per hour. Both engines are torquey, with lots of mid-range, and both are capable of breaking their rear tires loose in the dirt, should their riders be sufficiently brave to want to slide the bikes, feet-up, dirttrack-style, around corners.

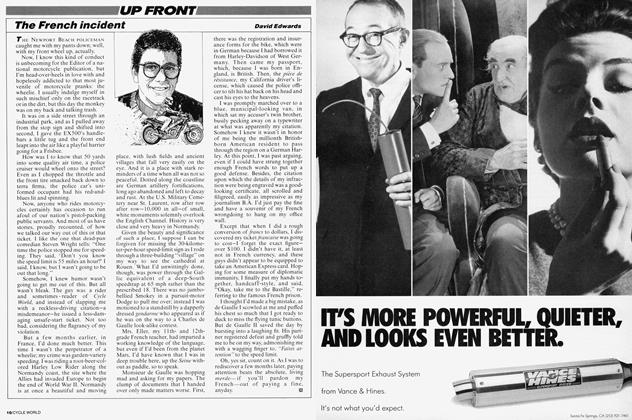

The Transalp’s suspension may be the best of any Honda streetbike; it’s progressive, and plush enough to require a really big bump to upset it. The fork’s 28-degree rake gives the bike fine straight-line stability, even if does slow the steering down just a little. Two factors that further enhance the Transalp experience are its narrowness—that makes it a terrific commute bike that’s easy to blast through traffic upon—and its fairing, which does a pretty good job of windblast protection. Additionally, the Transalp exudes the kind of slick detail finish that has become typical of Honda, and this attention to detail, not only in how the bike works but in how it looks, makes the Transalp a joy to ride.

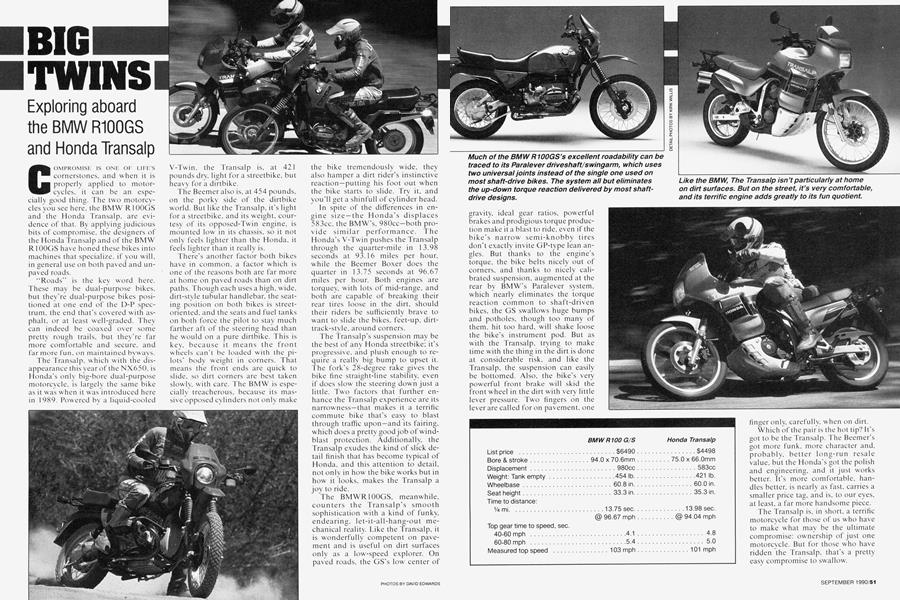

The BMWR100GS, meanwhile, counters the Transalp’s smooth sophistication with a kind of funky, endearing, let-it-all-hang-out mechanical reality. Like the Transalp, it is wonderfully competent on pavement and is useful on dirt surfaces only as a low-speed explorer. On paved roads, the GS's low' center of gravity, ideal gear ratios, powerful brakes and prodigious torque production make it a blast to ride, even if the bike’s narrow' semi-knobby tires don't exactly invite GP-type lean angles. But thanks to the engine’s torque, the bike belts nicely out of corners, and thanks to nicely calibrated suspension, augmented at the rear by BMW’s Paralever system, which nearly eliminates the torque reaction common to shaft-driven bikes, the GS swallows huge bumps and potholes, though too many of them, hit too hard, will shake loose the bike’s instrument pod. But as with the Transalp, trying to make time with the thing in the dirt is done at considerable risk, and like the Transalp, the suspension can easily be bottomed. Also, the bike’s very powerful front brake will skid the front wheel in the dirt with very little lever pressure. Two fingers on the lever are called for on pavement, one finger only, carefully, when on dirt.

DAVID EDWARDS

Which of the pair is the hot tip? It’s got to be the Transalp. The Beemer's got more funk, more character and, probably, better long-run resale value, but the Honda's got the polish and engineering, and it just works better. It’s more comfortable, handies better, is nearly as fast, carries a smaller price tag, and is, to our eyes, at least, a far more handsome piece.

The Transalp is, in short, a terrific motorcycle for those of us who have to make what may be the ultimate compromise: ownership of just one motorcycle. But for those who have ridden the Transalp, that's a pretty easy compromise to swallow.

BMW R100 G/S

$6490

Honda Transaip

$4498

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

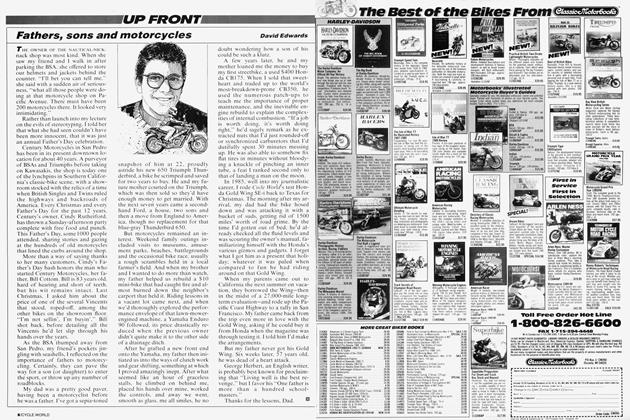

Up FrontFathers, Sons And Motorcycles

SEPTEMBER 1990 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeOut In the Midday Sun

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Discriminating Cheapskate

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersDinin' Dressers

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupConquest Goes Polish

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

Euro-News: Diesels And Better Beemers

SEPTEMBER 1990