TAKIN' IT TO THE STREETS

Drag racing on the far side of the law

JON F. THOMPSON

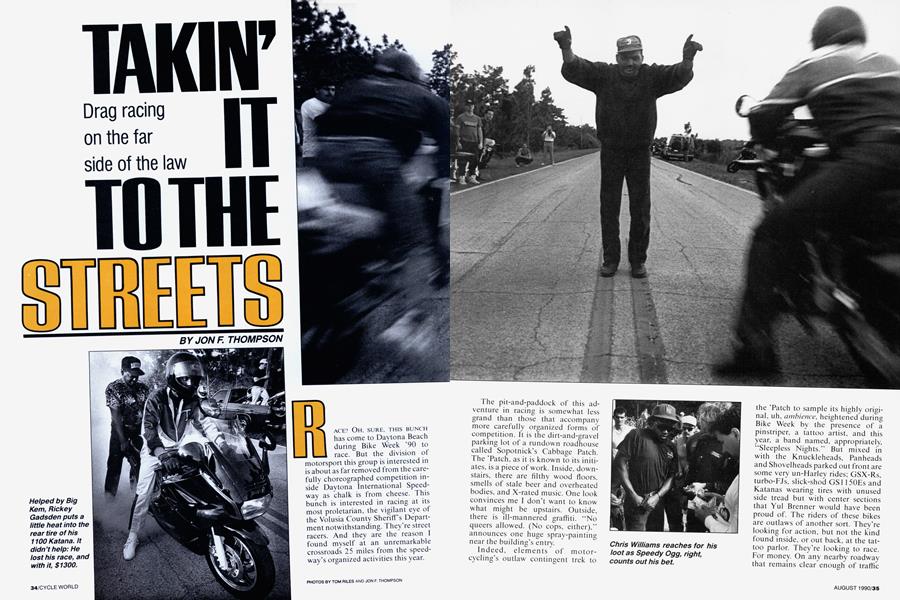

RACE? OH, SURE, THIS BUNCH has come to Daytona Beach during Bike Week `90 to race. But the division of motorsport this group is interested in is about as far removed from the carefully choreographed competition inside Daytona International Speed-way as chalk is from cheese. This bunch is interested in racing at its most proletarian, the vigilant eye of the Volusia County Sheriff's Department notwithstanding. They're street racers. And they are the reason I found myself at an unremarkable crossroads 25 miles from the speed-way’s organized activities this year.

The pit-and-paddock of this adventure in racing is somewhat less grand than those that accompany more carefully organized forms of competition. It is the dirt-and-gravel parking lot of a rundown roadhouse called Sopotnick’s Cabbage Patch. The ’Patch, as it is known to its initiates, is a piece of work. Inside, downstairs, there are filthy wood floors, smells of stale beer and overheated bodies, and X-rated music. One look convinces me I don't want to know what might be upstairs. Outside, there is ill-mannered graffiti. “No queers allowed. (No cops, either),” announces one huge spray-painting near the building’s entry.

Indeed, elements of motorcycling’s outlaw contingent trek to the 'Patch to sample its highly original, uh, ambience, heightened during Bike Week by the presence of a pinstriper, a tattoo artist, and this year, a band named, appropriately, “Sleepless Nights.” But mixed in with the Knuckleheads, Panheads and Shovelheads parked out front are some very un-Harley rides; GSX-Rs, turbo-FJs, slick-shod GSI 1 50Es and Katanas wearing tires with unused side tread but with center sections that Yul Brenner would have been proud of. The riders of these bikes are outlaws of another sort. They’re looking for action, but not the kind found inside, or out back, at the tattoo parlor. They’re looking to race. For money. On any nearby roadway that remains clear enough of traffic and cops long enough to get a drag race staged and run.

Highway Joe

“I love this shit, I just love it!" This earthy exultation is uttered by Highway Joe Branch, a bear of a man, here from Queens, New York. The cause of Highway Joe's joy is a negotiation. This is folk art in which two contestants, each with a hot bike and a stack

of greenbacks, determine whether or not they’ll race each other, and it so, for how much, and under what rules.

This gets very complicated. And very boisterous. Highway Joe, a retired real-estate salesman, can afford to stand back and watch. And he does, at least until the negotiations aet so heated he no longer can restrain himself. But mostly he relies on his two sons, Highway Joe Jr. and Little Highway, to handle the arrangements.

Highway Joe wears a huge lump on the right side of his skull, the result of an altercation with pavement in a drag-race crash. This hasn't slowed him down at all, his sons tell me.

During negotiations, though. Highway Joe often takes his baseball cap off. points to the lump, and says, encouraging a would-be competitor, “Sure, you can beat an old man who s got one of these. Branch s sons tell me he won more money street racing last year than did either of them.

Highway Joe just grins proudly at his sons, and says, “The family that speeds together stays together."

Talkin' trash

If you can imagine comedians Sam Kinnison and Richard Pryor in each others’ faces on the crucial and primal subjects of manhood, courage. honor and speed, then perhaps you can begin to imagine the passion and vigor with which pre-race negotiations are handled. For there are important matters to be discussed, matters which can make the difference between winning and losing, and that’s why dealings between serious players can take two hours or more. First of all, who is going to race? And on which bikes? Do the bikes use their nitrous-oxide systems, or not? Do they use their electricor air-shifters, or not? Will the race be flaggedoff by a mutually designated starter, or will someone get the break, or hit (that is, will someone be designated as the first to move, the drop of his clutch lever signaling the start of the race)? Will one or another of the racers be given an advantage? And if so, how many bikelengths? And, most important, how much money will be bet?

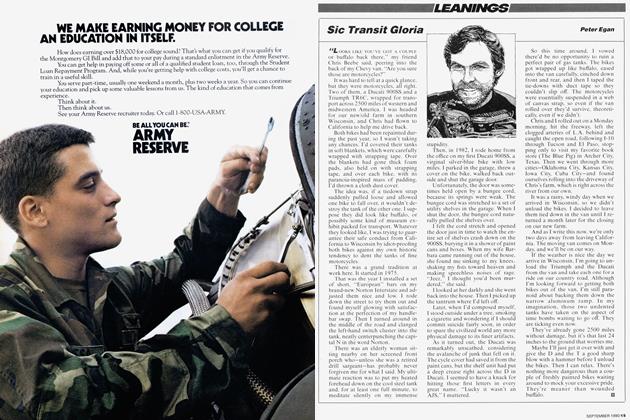

The Players, left to right:

To make money, the saying goes, you’ve got to spend money. Or at least be prepared to. The players here, on this day, are. The low bet is $20, although I’ve been told it’s not uncommon for the wagering to run to $ 10,000 and beyond.

“If we feelgood about (arace),” Little Highway tells me, “We’ll bet the house.” And indeed, impressive stacks of $ 100 bills suddenly materialize from the pockets of faded jeans when finally a race looks ready to go down. Money materializes not just in the hands of the racers. There’s also lots of sidebetting, so if $1300, the largest single race bet I saw, is wagered between racers, a lot more money is laid down by spectators.

But before anything else, the runners have to agree on ground rules, and that can take patience. This day, in the ’Patch’s parking lot, the negoti-

ations begin between Highway Joe Jr. and Big Kem “BK” Minor, a Philadelphia small businessman, here with his partner Bill “White Boy Billy” Voss, and their pair of Suzuki GS1 150Es. During the course of the two-hour haggle, the choice of bikes to be used, the pilots, the amount of money to be bet all change, as the contestants vie for the hit and the number of bikelengths they think will yield a fair match-up. Soon, Highway Joe Jr. is out of the picture.

“It’s hard to get a race. They’re a little afraid of us, we’re a little afraid of them,” he says philosophically.

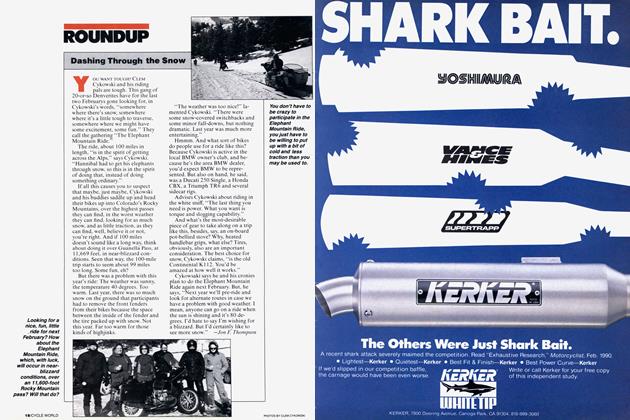

Now the talk is between Robert “Speedy” Ogg, here from Nashville with his pal Steve Miller, and Terry Jones, here from Orlando with his pi-

lot, Chris Williams, of whom he says proudly, “He’s just a black Jay Gleason, is all.”

Finally a deal is done and the contestants ride out to a lonely country road, where Williams smokes Miller.

“It’s basically stock.”

Most of the backroad drag racers take great pride in the fact that what they race are streetbikes, and they frown upon those, such as BK, White Boy Billy and Highway Joe, who have trucked their bikes here. This they see as an admission that those machines are specialist bikes, not real street machines. Ask any of them what they’ve done to their bikes. Never mind that the bike in question hunkers low to the ground and idles lumpily at 2000 rpm, the answer, inevitably, is, “Hey, it’s basically stock.”

Sure it is.

Yet even if that is true, the hardcore have found ways to shave tenths from the quarter-mile times of even the most-stock machines.

Craig Burgess, here from Dayton, Ohio, on his “basically stock” Katana 1 100, explains the tricks:

“First, there’s jetting and a pipe. Then you strap the front end down (compress the forks with a tie-down strap) so it doesn't wheelie; you lower the rear-end and make the shock fullsoft, drop the pressure in the rear tire, drop a tooth on the front sprocket, and rewire the horn button into the ignition so you can preload the shift lever with your foot and then shift as you fan the horn button with your thumb. Just messing with the chassis is worth two-, maybe three-tenths,” he confides.

But any bike that truly is a stocker is in the minority here. This is how Speedy Ogg, with 1 7 years of streetracing experience, here for the eighth straight year, explains it:

“The trick to this kind of racing is to be sneaky. The bike’s got to be fast, but it’s got to look slow. You want to know what I got in my bike (a sun-faded Suzuki)? Buy it.” Then he

thinks a bit, and adds, “Actually, it’s a basically stock GSX-R750. Of course, it’s got nitrous. And it’s motor is 1 109cc, it’s got headwork and a lock-up clutch, 36mm carbs bored out to 40mm. It’ll do 9.8s, 9.9s, at 1 50 miles an hour, on a street tire.”

Outlaws

But wait: Aren't there dragstrips, complete with timing apparatus, readily available? What are these guys doing out here in the Florida sticks, on the public highways, perilously close to the myopic eye of societal norms which recognize this pastime as antisocial? Why risk the wrath of people like Corporal Joe Deemer, of the Volusia County Sheriff’s Department, who thunders, “Street racing? We don’t tolerate it!”

Yet despite the threat of jail time, despite the potential for injury, the street racing goes on. Asked what he, a white-collar computer salesman, is doing in Florida, taking on all com-

ers, Craig Burgess thinks for a moment, then says, metaphysically, “The only thing I fear more than dying is not living.”

Speedy Ogg is less enigmatic. “It’s a challenge to see who’s the baddest of the bad,” he says. Bill Voss is here, he says, because of the money and the excitement. And Highway Joe has his own perspective: “Why, it’s the most-important thing a man can do. It makes an old man feel young, a young man feel mature. You have to do things for yourself; there’s no officials to think for you.”

Equally compelling is this question; Why are so many of the street racers here black? Big Kem Minor, a black, tells me, “Street racing’s illegal. The whites want to keep their licenses. The blacks don’t care.” Highway Joe, also black, says, “It’s exciting for black people to be on the edge of the law.” And Jones, a white, says, “I don't know, but the blacks like to race, and they sure are competitive.”

Race time

All this thoughtfulness is broken up when Speedy Ogg reopens negotiations. He bargains for a startline advantage of five bikelengths, and the break, for $50; then he gets seven and the break for $75, but on his buddy’s GSX-R1 100, instead of his own bike. This agreement seems to break the dam, and soon, Chris Williams has a race against a young IDBA racer named Rickey Gadsden, down from New Jersey with his Katana 1 100.

And so the entire circus temporarily abandons the Cabbage Patch for a forlorn section of highway deep in the Florida back country.

An hour-long expression of quarter-mile joy follows, the runners going off one pair right after another, until, just at sunset, with two racers lined up head-to-head and the starter about to drop his hand, three ominous sedans drift at high speed around the curve leading to this straight stretch. Someone yells, “Cops! Cops! Let’s split!”

Cops, indeed. Speaking over his car’s public-address system, the driver of the first patrol car says, “Okay, we got more units and a copter cornin’. This is your one chance to get clear.” And the area instantly is vacant. Photographer Tom Riles and I are into our U-Wreck-It and gone, thankfully blended into the anony-

mous flow of traffic of the first busy highway we can find.

The racers also disappear, having, apparently, evaporated into the atmosphere. The only evidence of the activity here this day are the strips of black rubber that begin at the 35mph sign the racers have been using for a startline. That, and the echo of the flick of $100 bills, the smell of burnt nitrous, and the sense that we’ve all barely escaped jail.

It’s oddly heady stuff, this street racing. Antisocial? Yes. Inexcusable? Absolutely. But if one of the most American of traits is to question authority, it just might be possible to argue that this is one of the most American of pastimes. B3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

August 1990 -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

August 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1990 -

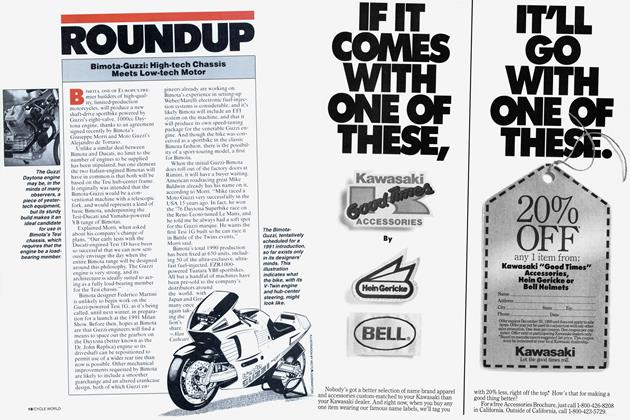

Roundup

RoundupBimota-Guzzi: High-Tech Chassis Meets Low-Tech Motor

August 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupHonda Prices: What Was Up Goes Down

August 1990 By Jon F. Thompson