Coming to America

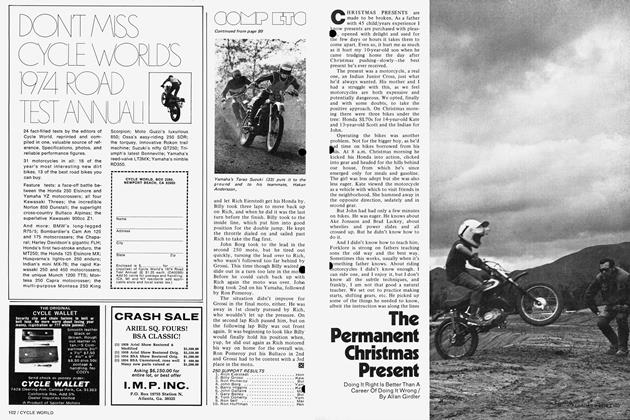

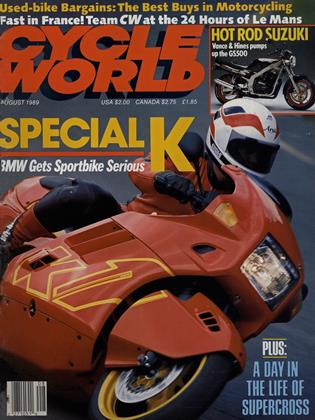

BMW’s new K1 flagship launched for a fall invasion

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

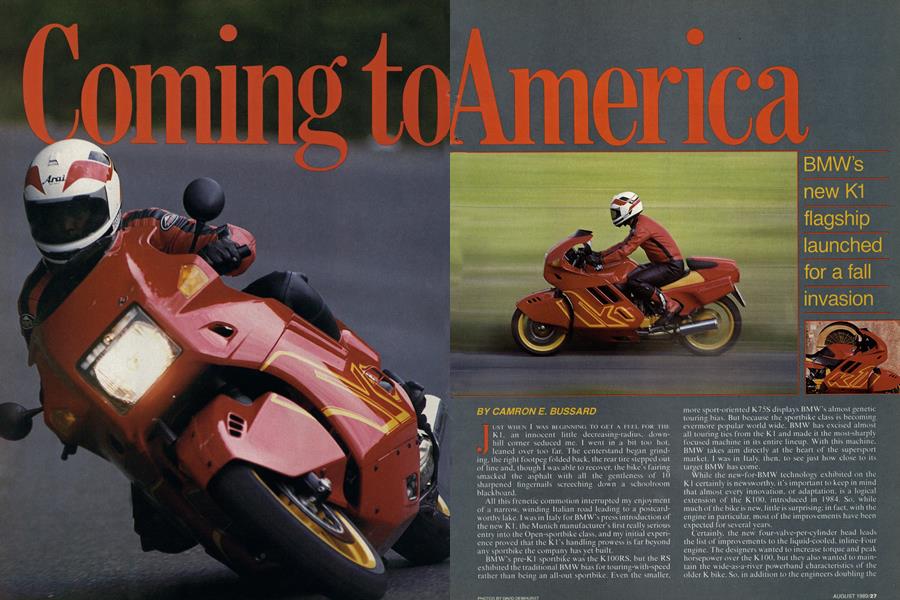

JUST WHEN I WAS BEGINNING TO GET A FEEL FOR THE K1, an innocent little decreasing-radius, down-hill corner seduced me. I went in a bit too hot, leaned over too far. The centerstand began grinding, the right footpeg folded back, the rear tire stepped out of line and, though I was able to recover, the bike's fairing smacked the asphalt with all the gentleness of 10 sharpened fingernails screeching down a schoolroom blackboard.

All this frenetic commotion interrupted my enjoyment of a narrow, winding Italian road leading to a postcardworthv lake. I was in Ttaly for BMW's press introduction of the new K I. the Munich manufacturer's first really serious entry into the Open-sportbike class, and my initial experience proved that the Kl’s handling prowess is far beyond any sportbike the company has yet built.

BMW's pre-Kl sportbike was the KI OCRS, but the RS exhibited the traditional BMW bias for touring-with-speed rather than being an all-out sportbike. Even the smaller. more sport-oriented K75S displays BMW’s almost genetic touring bias. But because the sportbike class is becoming evermore popular world wide. BMW has excised almost all touring ties from the KI and made it the most-sharply focused machine in its entire lineup. With this machine, BMW takes aim directly at the heart of the supersport market. 1 was in Italy, then, to see just how close to its target BMW has come.

While the new-for-BMW technology exhibited on the K1 certainly is newsworthy, it’s important to keep in mind that almost every innovation, or adaptation, is a logical extension of the KI00. introduced in 1984. So. while much of the bike is new. little is surprising; in fact, with the engine in particular, most of the improvements have been expected for several years.

Certainly, the new four-valve-per-cylinder head leads the list of improvements to the liquid-cooled, inline-Four engine. The designers wanted to increase torque and peak horsepower over the K100. but they also wanted to maintain the wide-as-a-river powerband characteristics of the older K bike. So. in addition to the engineers doubling the number of valves, they reshaped the combustion chambers and narrowed the included valve angles. Also, BMW claims that the new engine does not require periodic valve adjustments, and so has replaced the adjustment spacers with solid tappets. If a valve adjustment is ever neededon an extremely high-mileage engine, for example—replacing the tappet with one of a different thickness will take care of things. Furthermore, this four-valve engine revs more quickly than the two-valve version, partly because of improved breathing and partly because of a reduction in reciprocating mass, as the crankshaft, connecting rods and pistons have been lightened by a total of about 2.8 pounds.

On the older K-series bikes, oil seeping past the rings caused the engine to smoke whenever the bike had been parked on the sidestand, so the designers modified the piston rings themselves to prevent oil from leaking into the heads when the engine is at rest. Out of the 20 or so Kls in Italy, only one of the machines filled the air with oil-blue smoke clouds after start-up.

Internally, the K1 engine’s 67 x 70mm bore and stroke are the same as the older powerplant, but the compression ratio jumps from 10.2:1 to 1 1.0:1. With a 70mm stroke, the BMW adheres to a relatively low 8750-rpm redline, so the power increases don’t come from higher engine speeds. Nonetheless, as a result of the cylinderhead changes and a new exhaust system, the engine output was bumped up by a claimed 10 horsepower, from 90 to 100, and the torque went from 64 to 74 foot-pounds.

Although changes made to the engine are less than> earth-shaking, the real-world difference between it and its two-valve counterpart is striking. The Kl possesses a midrange power punch that seems as strong and smooth as that of a Hurricane 1000. From 2000 rpm up, the bike pulls strongly, but when the tach needle hits 4500 rpm, the bike leaps forward, pulling hard until just before redline, where the power begins to taper. Because it still spots some of its competition as much as 38 horsepower, the K l won’t win an all-out, top-speed run, but should still be capable of pulling a respectable 150 miles per hour.

To help the bike’s chassis deal with the uprated engine performance, BMW’s engineers used thicker tubes in the Kl’s frame than they did with the K100RS’. As a result, the bike’s chassis is extremely stiff and at high speeds, exhibits none of the flawed handling habits of the K100RS: At paces that would have the RS wobbling, weaving and grinding, the Kl is just hitting its stride.

The Kl’s improved frame is matched by its suspension. The 41.7mm front fork is far and away the best BMW has yet put on a production motorcycle. Built by Marzocchi, the fork has firm damping combined with highly progressive springs. Also, the Marzocchi specification includes teflon-coated bushings to reduce fork-slider stiction. Over small bumps and pavement ripples, initial fork travel is soft and slow, but as speeds increase and the fork moves into the deeper range of its travel, the springs gets stiffer and the damping action greater. The result is a taut ride that stays compliant regardless of speed.

At the rear, BMW has installed its Paralever system, introduced on the R100GS dual-purpose bike. This system adds about two inches to the K’s wheelbase and a few extra pounds, but the result is an almost-total lack of driveshaft-torque reaction, one of the handling bugaboos that shaft-driven motorcycles have had to suffer through. With Paralever, the machine does not lift its tail under acceleration, and the chassis will not fall on its suspension-eating up precious ground clearance—if power is chopped on the entrance to a corner.

Because the Paralever system takes care of the usual shaft-drive torque reaction, BMW was able to fit a shock with a softer spring than that of the K100. For riders over l 75 pounds, the spring is just about right, but riders carrying less mass will probably find the spring too stiff and may want to opt for a lighter one. As it is, when set on the lighter preload settings, the rear shock provides a soft, compliant ride, but allows a rider to quickly use up the bike’s cornering clearance, as I discovered. Bumped up a couple of notches, the ground-clearance problem lessens considerably and high-speed stability improves, especially over rough roads, although this comes, of course, at the expense of ride quality. Remember, though, this BMW is a pure sportbike, not a sport-touring machine, so it seems reasonable for BMW’s engineers to have sacrificed a little comfort for more control.

And improved control is exactly what you get from the Kl: Its handling is razor sharp. The bike bends easily into corners, feeling much lighter than its claimed 571 pounds. Only at walking paces does the rider feel the bike’s weight. Fortunately, the handlebar provides plenty of leverage, even at the slow speeds necessary when negotiating traffic jams on the tight, winding, cobblestone streets prevalent in the villages throughout Italy.

Thanks to its stiff chassis and fine suspension, the Kl works corners with a rock-solid stability much like Yamaha’s FZRIOOO, in the minds of many, this year’s premier sport implement. It stays effortlessly on line and requires only a light push on the bar to change lines in midturn. In tighter corners, the K l consents to deep entrances and to being slammed hard over, and doesn’t wiggle, shake or otherwise resist aggressive riding techniques.

Much of the confidence the bike instills can be attributed to its tires. The first machines are fitted with Michelin M59 radiais, but later bikes also will be available with Dunlop and Metzeler radiais. Regardless of brand, the tires are the widest by far that BMW has ever used—a 160/ 80-18 mounted on the rear, 4.5-inch-wide rim and a 120/ 70-1 7 on the 3.5-inch-wide front. The Michelins gave the bike great traction and the round profile on the front helped to make the transition from straight-up to full-lean effortless and progressive.

Those premium tires will be appreciated in light of the Kl’s Brembo front brake. It is a precise, powerful, twindisc, four-piston unit that provides great feedback whether the rider is feathering off speed in a corner or howling the front tire in a full-on panic stop. And in most cases, a single finger will take care of the braking duties. As an added incentive for American riders, every Kl imported here will come with BMW’s ABS anti-lock brakes as standard equipment.

Given the tremendous sporting potential of the Kl, the folks at BMW could have easily gone overboard and designed racer-crouch ergonomics to match. Instead, they opted for a more-comfortable solution. The handlebar is low, but it is fairly wide, and while the footpegs are high and rearward for a BMW, they are still not as tucked-up as those on a GSX-R or a FZR. The overall riding position> falls between that of the Hurricane 1000 and the Katana l 100, but the K l has a seat with a more comfortable shape and slightly firmer foam than either of those two bikes.

There is more room behind the Kl's fairing than on the other K-bikes, so most riders will not bang their knees on the inner panels, a common complaint with the K100RS. Overall, the fairing does a pretty good job of protecting the rider from the elements, with the short windscreen directing airflow toward the rider’s shoulders.

One thing the fairing doesn’t do, however, is duct engine heat away from the rider, meaning, unfortunately, that left shins and inner thighs get roasted. Other K-bikes run a little on the warm side, but the Kl puts ofifexcessive heat. It may be that in their quest for the most aerodynamic motorcycle shape possible, BMW’s engineers traded rider comfort for aero-efficiency.

Because the machines ridden by the press in Italy were the very first off BMW’s production lines, some details were a little ragged and may be improved as BMW sorts things out. Still, nearly every journalist complained about the styling and the fit and finish. The styling, while a little unorthodox and bulky, is a matter of personal taste: Everywhere I parked the bike, it drew a crowd of Italian admirers, crying “moto-bella. ”

But if styling is personal taste, the quality of the fit and finish is another matter entirely. Judging from the bikes I saw, BMW has allowed the Kl to fall behind not only its own products, but those from Japan as well. The bodywork seams didn’t match, the glovebox doors on the tail section fit poorly and the inner panels of those boxes, as well as that of the tool compartment in the fairing, are roughly finished and offer sharp edges to unsuspecting fingers. And the screws which hold the two-piece front fender together are unsightly and crude. For a motorcycle that in all likelihood will cost $ l 3,000, these are justified complaints.

For now, however, the essential consideration about the Kl is how it works, and there it is difficult to fault the machine. It pushes BMW into the future with overall performance that could prove equal to, if not better than, that of its competition. I'll table the final judgement until Cycle World can test a U.S.-model Kl in the company of other bikes, however.

When the K l does come to America in the fall of 1990, some of its fit-and-finish problems should be cleared up. I hope so. A motorcycle that works this well and costs this much should be absolutely the best it can be. Anything less is an injustice. lá

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

August 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

August 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupNew, Top-Secret Triumph Revealed

August 1989 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupFor Japan Only: the High-Tech 250s

August 1989 By David Edwards