THE 250cc TRAILBIKES

CW COMPARISON

Whether you're after trailside giggles or enduro-racing gold, look no farther

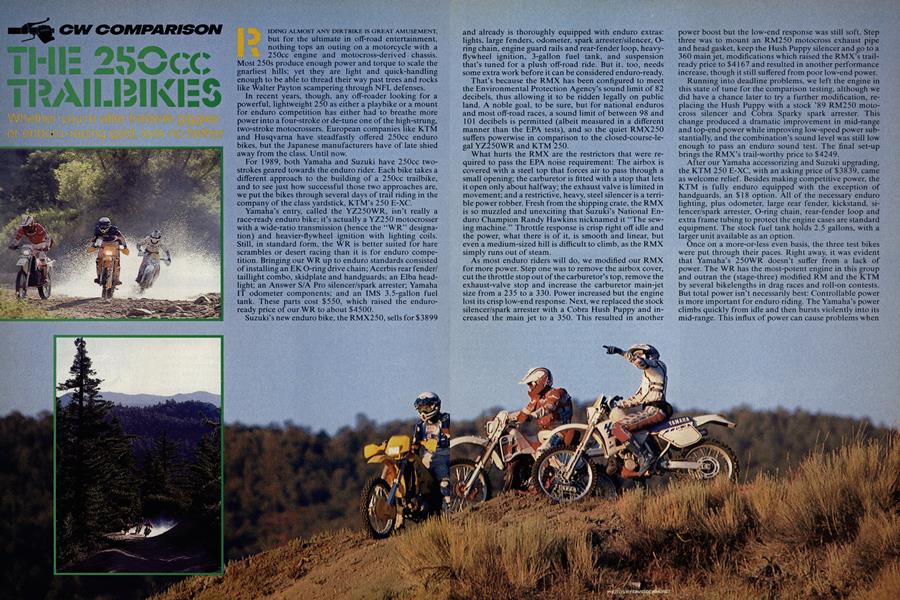

RIDING ALMOST ANY DIRTBIKE IS GREAT AMUSEMENT, but for the ultimate in off-road entertainment, nothing tops an outing on a motorcycle with a 250cc engine and motocross-derived chassis. Most 250s produce enough power and torque to scale the gnarliest hills; yet they are light and quick-handling enough to be able to thread their way past trees and rocks like Walter Payton scampering through NFL defenses.

In recent years, though, any off-roader looking for a powerful, lightweight 250 as either a playbike or a mount for enduro competition has either had to breathe more power into a four-stroke or de-tune one of the high-strung, two-stroke motocrossers. European companies like KTM and Husqvarna have steadfastly offered 250cc enduro bikes, but the Japanese manufacturers have of late shied away from the class. Until now.

For 1989, both Yamaha and Suzuki have 250cc twostrokes geared towards the enduro rider. Each bike takes a different approach to the building of a 250cc trailbike, and to see just how successful those two approaches are, we put the bikes through several days of trail riding in the company of the class yardstick, KTM’s 250 E-XC.

Yamaha’s entry, called the YZ250WR, isn’t really a race-ready enduro bike; it’s actually a YZ250 motocrosser with a wide-ratio transmission (hence the “WR” designation) and heavier-flywheel ignition with lighting coils. Still, in standard form, the WR is better suited for hare scrambles or desert racing than it is for enduro competition. Bringing our WR up to enduro standards consisted of installing an EK O-ring drive chain; Acerbis rear fender/ taillight combo, skidplate and handguards; an Elba headlight; an Answer S/A Pro silencer/spark arrester; Yamaha IT odometer components; and an IMS 3.5-gallon fuel tank. These parts cost $550, which raised the enduroready price of our WR to about $4500.

Suzuki’s new enduro bike, the RMX250, sells for $3899 and already is thoroughly equipped with enduro extras: lights, large fenders, odometer, spark arrester/silencer, CDring chain, engine guard rails and rear-fender loop, heavyflywheel ignition, 3-gallon fuel tank, and suspension that’s tuned for a plush off-road ride. But it, too, needs some extra work before it can be considered enduro-ready.

That’s because the RMX has been configured to meet the Environmental Protection Agency’s sound limit of 82 decibels, thus allowing it to be ridden legally on public land. A noble goal, to be sure, but for national enduros and most off-road races, a sound limit of between 98 and 101 decibels is permitted (albeit measured in a different manner than the EPA tests), and so the quiet RMX250 suffers powerwise in comparison to the closed-course-legal YZ250WR and KTM 250.

What hurts the RMX are the restrictors that were required to pass the EPA noise requirement: The airbox is covered with a steel top that forces air to pass through a small opening; the carburetor is fitted with a stop that lets it open only about halfway; the exhaust valve is limited in movement; and a restrictive, heavy, steel silencer is a terrible power robber. Fresh from the shipping crate, the RMX is so muzzled and unexciting that Suzuki’s National Enduro Champion Randy Hawkins nicknamed it “The sewing machine.” Throttle response is crisp right off idle and the power, what there is of it, is smooth and linear, but even a medium-sized hill is difficult to climb, as the RMX simply runs out of steam.

As most enduro riders will do, we modified our RMX for more power. Step one was to remove the airbox cover, cut the throttle stop out of the carburetor’s top, remove the exhaust-valve stop and increase the carburetor main-jet size from a 235 to a 330. Power increased but the engine lost its crisp low-end response. Next, we replaced the stock silencer/spark arrester with a Cobra Hush Puppy and increased the main jet to a 350. This resulted in another power boost but the low-end response was still soft. Step three was to mount an RM250 motocross exhaust pipe and head gasket, keep the Hush Puppy silencer and go to a 360 main jet, modifications which raised the RMX’s trailready price to $4167 and resulted in another performance increase, though it still suffered from poor low-end power.

Running into deadline problems, we left the engine in this state of tune for the comparison testing, although we did have a chance later to try a further modification, replacing the Hush Puppy with a stock ’89 RM250 motocross silencer and Cobra Sparky spark arrester. This change produced a dramatic improvement in mid-range and top-end power while improving low-speed power substantially, and the combination’s sound level was still low enough to pass an enduro sound test. The final set-up brings the RMX’s trail-worthy price to $4249.

After our Yamaha accessorizing and Suzuki upgrading, the KTM 250 E-XC, with an asking price of $3839, came as welcome relief. Besides making competitive power, the KTM is fully enduro equipped with the exception of handguards, an $ 18 option. All of the necessary enduro lighting, plus odometer, large rear fender, kickstand, silencer/spark arrester, O-ring chain, rear-fender loop and extra frame tubing to protect the engine cases are standard equipment. The stock fuel tank holds 2.5 gallons, with a larger unit available as an option.

Once on a more-or-less even basis, the three test bikes were put through their paces. Right away, it was evident that Yamaha’s 250WR doesn’t suffer from a lack of power. The WR has the most-potent engine in this group and outran the (stage-three) modified RM and the KTM by several bikelengths in drag races and roll-on contests. But total power isn’t necessarily best: Controllable power is more important for enduro riding. The Yamaha’s power climbs quickly from idle and then bursts violently into its mid-range. This influx of power can cause problems when climbing extremely dry, or extremely wet, hills. Crawling along the side of a hill was also a challenge with our WR. The bike’s low-end power was erratic under slow-speed, heavy-load conditions, especially with an aftermarket spark arrester clamped on.

Complete rider control best describes the KTM engine’s characteristics. It has an ideal combination of horsepower, flywheel weight and power delivery. The engine is very responsive off idle and the power builds rapidly but controllably through a wide mid-range before signing off suddenly. This smooth, electric-motor-type of power flow reduces rider effort, and all our riders—Pro to Novicefound the KTM much less tiring to ride in difficult terrain.

The KTM also has the best clutch action of the three bikes, as the lever pull is easy and the clutch engages progressively. The Yamaha WR’s clutch engages suddenly, motocross style, which makes control in tight places extremely difficult and tiring. The RMX clutch works smoothly but it,too,is more sudden in engagement than is ideal for an enduro bike. All of the bikes shift positively and have well-chosen gear ratios, while the RMX takes the honors for shifting smoothness.

Of course, all three machines are equipped with modern suspensions, but the YZ’s stadium-motocross-derived valving is less than ideal for trail use: Compression damping is excessive at both ends, which results in a harsh, pounding ride, even when the external damping adjusters are set at full-soft. Adding to the suspension-compliance problems, especially in rocky terrain, was the YZWR’s hard-compound, Dunlop K702 19-inch rear tire. We never found a situation where the rear tire hooked-up well—it slips and spins constantly.

Though in the past we’ve had trouble dialing in the suspensions on KTMs, the 1989 E-XC’s White Power components worked well for most of our riders. The fork does exhibit some initial harshness in rocks and squareedged ruts, but overall it works fairly well with the compression and rebound knobs in their number 2 positions. The shock was smooth and compliant with the compression knob on 2, the rebound on number 5.

Even so, the KTM suspension is no match for the plushness of the RMX suspension. Control and comfort is excellent with any level rider aboard. Tree roots and rocks are simply swallowed up without the bike veering offline. We left the fork and shock set at their standard, delivered settings of full-soft on the fork compression, six clicks out on the rebound damping. The shock was set at 10 clicks out on compression and rebound.

Properly set up, these lightweight, motocross-based 250s are a delight to ride on a twisty trail. They steer with precision, are easily flicked back and forth through essturns, jump straight and generally add a high level of excitement to any off-road excursion. All are capable of providing gobs of trail-riding thrills and all are capable of picking up an enduro trophy, so picking an overall winner here wasn’t an easy chore.

But when it came down to cost and effectiveness in stock trim, every one of our riders chose the KTM 250 EXC as the best. It’s the only bike in this group that’s enduro-ready in stock form.

Suzuki’s RMX250 slid into second spot. The RMX is a light, quick-handing gem that’s severely flawed by its choked-down engine. Converting the RMX’s underpowered engine into a competitive, exciting engine is a straightforward procedure, but it means that a ridable RMX will cost $500 more than a KTM.

Yamaha’s YZ250WR has a lot of desirable traits and it’s a good starting point for building an enduro bike, but it won’t be cheap. As noted, our test bike cost $4500 with the enduro accessories—and it still needs a kickstand and suspension modifications. Figure on spending another $300, which brings the price of the Yamaha to approximately $4800. That’s $960 more than the KTM.

So, KTM’s 250 E-XC turns out to be not only the best enduro bike of this bunch, but it’s ready to roost without additions or modifications and it will get you onto the trail for less cash. That’s a tough combination to beat.

KTM 250 E-XC

$3839

Suzuki RMX250

$3899

Yamaha YZ WR

$3949

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1989 -

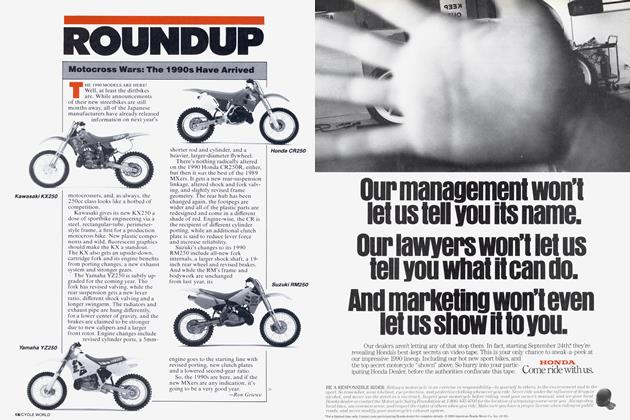

Roundup

RoundupMotocross Wars: the 1990s Have Arrived

October 1989 By Ron Griewe -

Roundup

RoundupThe Harley-Davidson Success Story

October 1989 By Jon F. Thompson