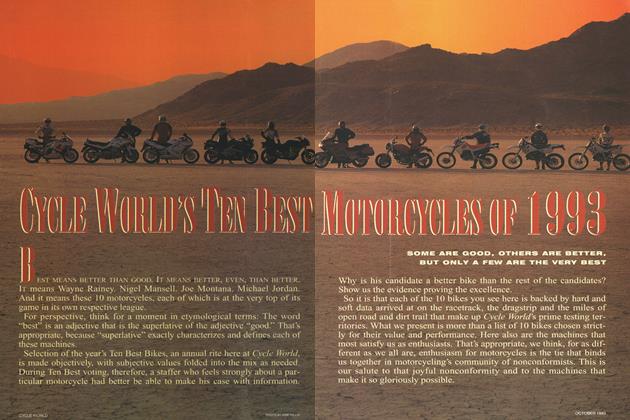

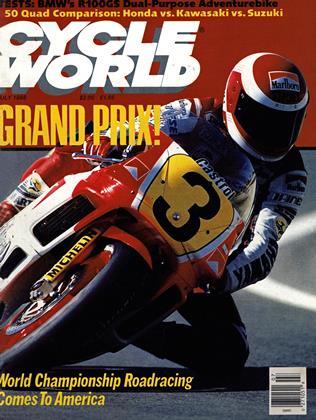

LAGUNA SECA 250 GRAND PRIX

Everyone knew an American could win, but nobody thought it would be this American

STEVE ANDERSON

WAYNE RAINEY NEVER DID IT. RICHARD Schlachter, though he often set fast lap times, never tasted the champagne. These champions of American roadracing both tried to win a 250 GP. Neither ever succeeded. In fact, during Kenny Roberts' entire European career, even The King won but two 250 GPs. Not until Freddie Spencer captured the 250 and 500cc World Championships in 1985 did an American pose a real threat in the 250 class. And when Spencer left the 2 SOs, so did the American threat. So, the European GP regulars were more than a little shocked to find three Americans among the top five fin ishers in the Laguna Seca 250cc GP. And their minds

reeled when they considered who had won the race: Jimmy Filice, a virtual unknown in world-championship circles competing in his very first GP. If the winner had been American 250 champ John Kocinski, well, they could have understood. But an American rider whose reputation even in his own country wasn't all that great?

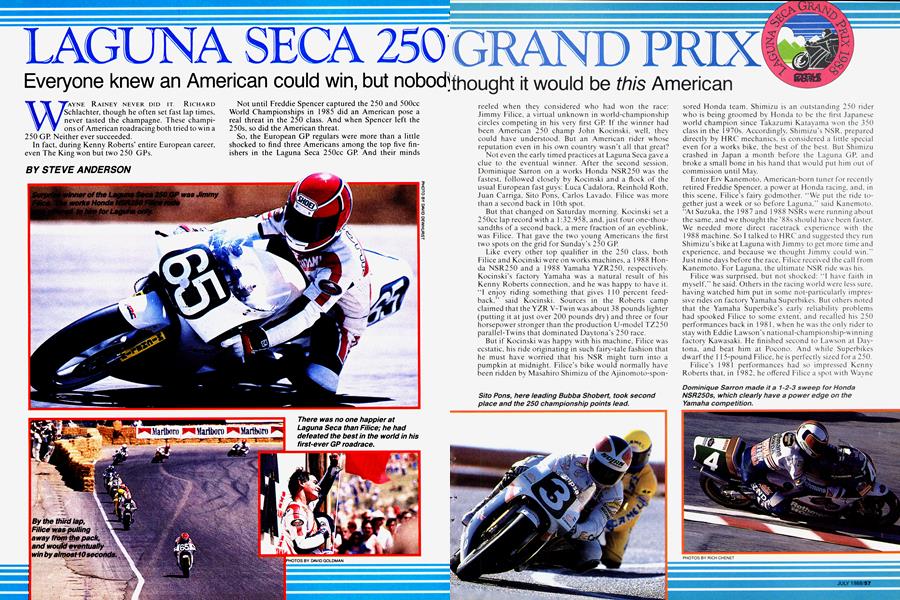

Not even the early timed practices at Laguna Seca gave a clue to the eventual winner. After the second session, Dominique Sarron on a works Honda NSR250 was the fastest, followed closely by Kocinski and a flock of the usual European fast guys: Luca Cadalora, Reinhold Roth. Juan Carriga, Sito Pons, Carlos Lavado. Filice was more than a second back in 10th spot.

But that changed on Saturday morning. Kocinski set a 250cc lap record with a 1:32.958, and, just four one-thousandths of a second back, a mere fraction of an eyeblink, was Filice. That gave the two young Americans the first two spots on the grid for Sunday’s 250 GP.

Like every other top qualifier in the 250 class, both Filice and Kocinski were on works machines, a 1988 Honda NSR250 and a 1988 Yamaha YZR250, respectively. Kocinski’s factory Yamaha was a natural result of his Kenny Roberts connection, and he was happy to have it. “I enjoy riding something that gives 1 10 percent feedback,” said Kocinski. Sources in the Roberts camp claimed that the YZR V-Twin was about 38 pounds lighter (putting it at just over 200 pounds dry) and three or four horsepower stronger than the production U-model TZ250 parallel-Twins that dominated Daytona’s 250 race.

But if Kocinski was happy with his machine. Filice was ecstatic, his ride originating in such fairy-tale fashion that he must have worried that his NSR might turn into a pumpkin at midnight. Filice’s bike would normally have been ridden by Masahiro Shimizu of the Ajinomoto-spon-

sored Honda team. Shimizu is an outstanding 250 rider who is being groomed by Honda to be the first Japanese world champion since Takazumi Katayama won the 350 class in the 1970s. Accordingly, Shimizu’s NSR, prepared directly by HRC mechanics, is considered a little special even for a works bike, the best of the best. But Shimizu crashed in Japan a month before the Laguna GP. and broke a small bone in his hand that would put him out of commission until May.

Enter Erv Kanemoto, American-born tuner for recently retired Freddie Spencer, a power at Honda racing, and, in this scene, Filice’s fairy godmother. “We put the ride together just a week or so before Laguna,” said Kanemoto. “At Suzuka, the 1987 and 1988 NSRs were running about the same, and we thought the ’88s should have been faster. We needed more direct racetrack experience with the 1988 machine. So I talked to HRC and suggested they run Shimizu’s bike at Laguna with Jimmy to get more time and experience, and because we thought Jimmy could win." Just nine days before the race. Filice received the call from Kanemoto. For Laguna, the ultimate NSR ride was his.

Filice was surprised, but not shocked: “I have faith in myself,” he said. Others in the racing world were less sure, having watched him put in some not-particularly impressive rides on factory Yamaha Superbikes. But others noted that the Yamaha Superbike’s early reliability problems had spooked Filice to some extent, and recalled his 250 performances back in 1981, when he was the only rider to stay with Eddie Lawson’s national-championship-winning factory Kawasaki. He finished second to Lawson at Daytona, and beat him at Pocono. And while Superbikes dwarf the 1 1 5-pound Filice, he is perfectly sized fora 250.

Filice’s 1981 performances had so impressed Kenny Roberts that, in 1982, he offered Filice a spot with Wayne

Rainey on his 250 Grand Prix team. But Filice wanted to stay in America and win the dirt-track championship before going to Europe, so he turned Roberts down. Though Filice won three Miles in 1983, he never realized his dirttrack dream, and his later Superbike results with Yamaha didn’t exactly have people bidding for his services. When plans fell through this past fall for a 1988 250 program in Europe, Filice was out of a ride; so the phone call from Kanemoto was the best news he had heard in a long time.

Along with Filice and Kocinski, the other American rider in the running at Laguna was Bubba Shobert, who used his American Number One status and his contacts at Honda to pry a 1987 NSR loose for Laguna. It was all part of Shobert’s long-range career planning. “I want a 500 GP ride next season,” said the Camel Pro champion, and riding the 250 at Laguna was intended to demonstrate he deserved it. He qualified 13th.

Next American 250-regular was expatriate Englishman Alan Carter on a production 1988 U-model TZ in 20th, almost two seconds behind Kocinski and Filice on their works machines. Kocinski’s teammate, Thomas Stevens, also on a TZ-U, noted that the TZ was “equal on corner speed and braking to the works bikes, but definitely down on acceleration and suspension.” So the American 250class regulars without factory bikes were really racing to be first privateer; no amount of talent was likely to overcome the advantage the factory 250s had.

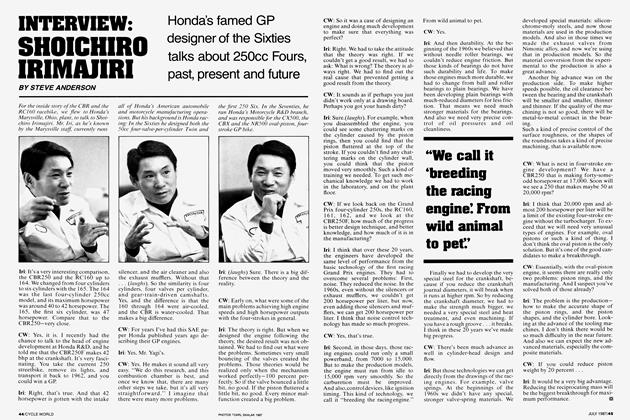

The race proved as much. Honda NSR-mounted Dominique Sarron jumped into the lead off the line, only to be passed by Shobert. But Shobert could stay in front only until the end of the third lap, when Filice took over and began pulling away. Behind him, Kocinski moved into second, and both Sito Pons and Sarron slipped past Shobert.

Filice never made a wrong move, and pulled farther in the lead with each lap. But for Kocinski, it proved to be a long day: “I knew it was going to be tough from the second lap. The Hondas were faster, and I needed a good drive off the corners to stay close to them. But the tires were too soft—I couldn’t get the drive out. I almost ran off the track twice.”

By the 13th lap, both Sarron and Pons managed to pass Kocinski, and Shobert began to creep up. Later, the Dunlop engineers would learn from the 250 race, deciding that a slightly harder compound was required for conditions slightly warmer than those that had prevailed in practice. They changed the tires on the Team Roberts 500s, but it was too late to help Kocinski.

Even so, Kocinski was able to pick up the pace and hold off Shobert. The running order was Filice, Pons, Sarron, Kocinski, Shobert, and it stayed that way. Filice, riding with eerie smoothness, lowered the lap record to 1:32.848, faster than any practice laps. He backed off only marginally for the last 10 laps of the race, and still won by 10 seconds. The Europeans were stunned; 250 races are won by feet, not by straightaways.

But Pons, thinking about world championship points, was happy with his second place. “I know Jim Filice is not doing the whole championship,” said the man who was in the points lead. Kocinski, who won’t be doing the entire GP season, either, expected so much of himself that he seemed to regard his fourth place, the first Yamaha home, as a failure; but for Kocinski, there’ll be other days, and better luck.

In contrast, Shobert’s fifth place was a victory of sorts; Laguna was, after all, only the second time he had raced a 250. According to him, “I knew I could do better than I qualified. I just wanted to get a good start.” Having accomplished both, he was all smiles in the pits, saying that “my goal is to get out of America a winner.”

If Shobert was happy, Filice was walking on air, with a smile that started somewhere so deep within that its glow could light a small city. He spent the first hour after the race talking to the HRC folk—an indication, perhaps, that this win could lead to a permanent GP ride.

A full week after the race, however, Filice still had not heard anything definite from Honda, meaning that he still didn’t have a ride for 1988. But his reputation has been retored, and optimism is in order: Something will come up. Filice feels that “If I had machinery like that NSR, I’d have a good chance at winning the world championship.”

After Laguna Seca, who’s going to argue with him? 51

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialAmerican Racewatching's Finest Hour

July 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeBad Day In Daly City

July 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsRadio Daze

July 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupSafer Cycling Through Electronics

July 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

July 1988 By Alan Cathcart