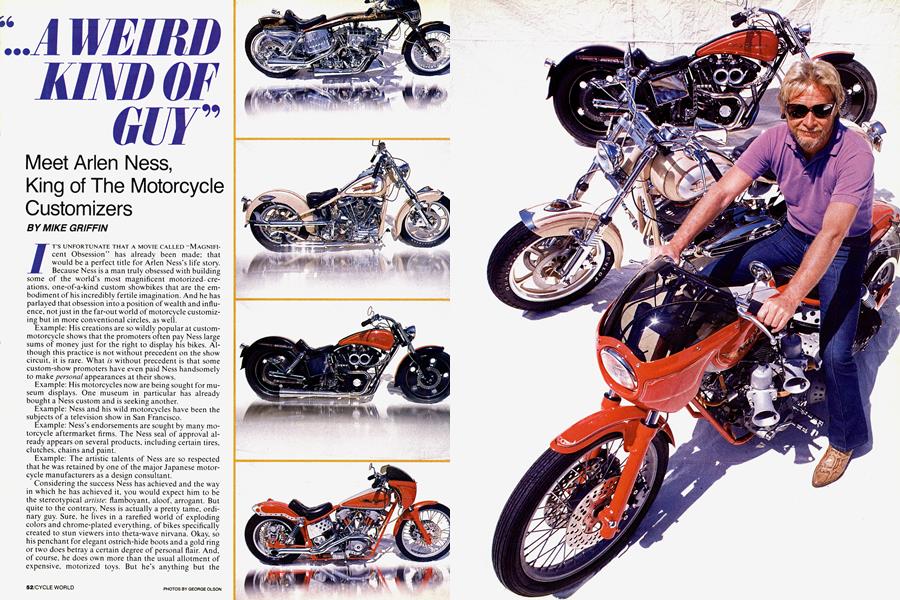

"...A WEIRD KIND OF GUY"

Meet Arlen Ness, King of The Motorcycle Customizers

MIKE GRIFFIN

IT'S UNFORTUNATE THAT A MOVIE CALLED "MAGNIFICent Obsession" has already been made; that would be a perfect title for Arlen Ness's life story. Because Ness is a man truly obsessed with building some of the world's most magnificent motorized creations, one-of-a-kind custom showbikes that are the embodiment of his incredibly fertile imagination. And he has parlayed that obsession into a position of wealth and influence, not just in the far-out world of motorcycle customizing but in more conventional circles, as well.

Example: Elis creations are so wildly popular at custommotorcycle shows that the promoters often pay Ness large sums of money just for the right to display his bikes. Although this practice is not without precedent on the show circuit, it is rare. What is without precedent is that some custom-show promoters have even paid Ness handsomely to make personal appearances at their shows.

Example: His motorcycles now are being sought for museum displays. One museum in particular has already bought a Ness custom and is seeking another.

Example: Ness and his wild motorcycles have been the subjects of a television show in San Francisco.

Example: Ness’s endorsements are sought by many motorcycle aftermarket firms. The Ness seal of approval already appears on several products, including certain tires, clutches, chains and paint.

Example: The artistic talents of Ness are so respected that he was retained by one of the major Japanese motorcycle manufacturers as a design consultant.

Considering the success Ness has achieved and the way in which he has achieved it, you would expect him to be the stereotypical artiste: flamboyant, aloof, arrogant. But quite to the contrary, Ness is actually a pretty tame, ordinary guy. Sure, he lives in a rarefied world of exploding colors and chrome-plated everything, of bikes specifically created to stun viewers into theta-wave nirvana. Okay, so his penchant for elegant ostrich-hide boots and a gold ring or two does betray a certain degree of personal flair. And, of course, he does own more than the usual allotment of expensive, motorized toys. But he’s anything but the flashy, temperamental artistic type.

Unless, of course, you define flamboyance with things such as a digital milling machine, a heliarc welder, a bandsaw, a motorcycle lift and a complete professional spray booth. If so, then, yes, Arlen Ness does live in high style, for he has all this equipment and more in the workshop of his posh home in Castro Valley, California.

Ness’s decision to live amidst the tools of his trade is a measure of his commitment to custom-bike building, an indication of the dedication and perseverance that have figured so heavily in his success. This is not someone who is casually involved or easily discouraged; this is a man who regularly gets far-fetched ideas and can't put them out of his head until they become reality. As Ness himself admits, “I’m a weird kind of guy. Once I get started on something, that’s it!” A man obsessed, in other words.

Ness has owned a retail custom-goodies store, called Arlen’s Motorcycle Ness-ecities, in the San Francisco suburb of San Leandro for quite a few years, but these days it’s managed by his 23-year-old son, Cory, an emerging customizing maven in his own right; and Bev, his wife of 28 years, looks after the books. That gives Ness a lot of free time for more creative pursuits, including prototyping parts for manufacture, designing new showbikes, restoring his 1952 Vincent Black Shadow, or dreaming up customizing ideas for one of his three Rolls Royces, his Chevypowered Manta or perhaps the Ferrari he’s had fitted with handmade bodywork. Or, you might find him tinkering with one of his several other vehicles, among them a chopped, sectioned and channeled van that seems no larger than a shoebox, and a chopped and radically lowered pickup truck that, well, if it were any lower, you'd stub your toe on it.

Interestingly, Ness’s retail shop is far from glitzy. From the outside, it’s your basic, b-flat motorcycle accessory store. Inside, over there beneath the sill of the showroom window, unseen by passers-by, languish dozen of old custom-show trophies. Through the dust, their inscriptions proclaim “Best This,” “Best That” or some other paean to Ness’s artistry. But they might as well be paperweights; they are simply in storage, not on display. Ness even has stopped entering his bikes in show competition, now displaying them for exhibition only. “I stopped competing 10 years ago,” he says matter-of-factly, “because it’s not fair to my customers.”

The shop’s showroom is crammed with a dozen or so of those glittering showbikes—some just completed, some well-traveled show-circuit veterans. But in that rather confined area is more chrome, gold plating, eyeball-searing paint, sinfully lavish engraving and brilliant mechanical rainbows of anodizing than you’re likely to see anywhere outside of a full-fledged custom-bike show. One’s eyes leap from the polished and louvered aluminum on one bike to the lush gold leafing on another; from the goldplated and engraved rockerboxes on this knucklehead to the deeply valenced art-deco fenders on that panhead; from the brutish supercharger fed by a pair of gaping S.U. carburetors on the shovelhead in the corner to the chromed, Gordian knot of exhaust plumbing on the famed, twin-Sportster-engined “Two Bad.” The estimated value of this part of Ness’s stable (there are several bikes elsewhere in various stages of construction) is in excess of $300,000.

But no matter how different one Nessbike might be from another, just about all of them have a unifying ethic of design: They all work. Ness is adamant about this, saying, “I build my bikes to be ridden.”

This conviction is, regrettably, far from universal in the motorcycle customizing community. To Ness, the idea of riding a showbike because (according to prevailing custom showbike rules) it has to be ridden is ridiculous. Ness showbikes are ridden because he wants them to be ridden, so they are designed to be ridden. In his mind, the glories of style should not come at the expense of function. Obviously, compromises must be struck at times—ground clearance vs. low overall profile, for example—so, a Ness custom is unlikely to keep pace with a sportbike in a canyonroad dice. But that’s the point, really: A Ness custom is not a sportbike or a stoplight racer or a typical Universal Japanese Motorcycle. It’s as far away from any of those as you can get.

A perfect example of Ness’s street practicality combined with artistic influence can be found in “The Pan,” a bike he constructed in 1982. Powered by a 1964 H-D panhead engine, it was built along the lines of the Indian Chief of the late 1940s and early 1950s. “I wanted it to look both old and modern,” claims Ness. So he combined one of his chrome-moly rigid-rear frames with contemporary fitments such as disc brakes front and rear.

This was a milestone, because until that time, brakes on custom bikes were treated with grudging acceptance. The rationale was that brakes provided too much visual clutter. So, traditionally, a custom used no front brake and just a wimpy drum in back. But, being more concerned about function than tradition, Ness began fitting modern brake systems to his bikes. And, which is so often the case with Ness “innovations,” the practice spread throughout the field.

So, too, has the use of contemporary suspension systems

on custom bikes spread, due in no small part to Ness’s influence. The traditional problem for customizers was that, to achieve a properly low-slung profile, it usually was necessary to eliminate the aft part of the frame, including the swingarm and shock absorbers, and to fit in its place a non-suspended sub-frame called, for obvious reasons, a “hardtail.” But Ness, who had sold more than a few rigid frames in his own right, believed that a low profile and a rear suspension didn’t have to be mutually exclusive. So he developed swingarm frames for H-D Sportsters and Big Twins, unquestionably the machines of choice for custom builders. With a seat height around two inches lower than stock, the frames offer a lower profile and at least some improvement in riding comfort. Hey, two inches of wheel travel is better than no inches.

What’s more, Ness’s use of Harley, Ceriani and, occasionally, Honda front forks did not go unnoticed by fellow custom builders, either—although he refuses to take credit for the diminishing popularity of undamped girder and springer front ends, or for the increasing use of telescopic forks on custom bikes. He'll admit to helping the trend gain popularity, but claims that it already had quite a bit of momentum. Still, no one can dispute that this quiet, almost enigmatic Californian has had enormous impact on the customizing scene, playing the lead role in its growth from a hobby-level activity to a full-blown industry.

It was Ness, in fact, who pioneered the popular “Bay Area” look several years ago, a style of custom based on Milwaukee-powered machines (“I’ll always be a Harley guy,” he says resolutely) having long and extremely low proportions. Other characteristics of the look include a radical steering-head angle (40 degrees, give or take a few), small fuel tanks, smaller seats and narrow-gauge fork legs embracing a skinny front wheel.

“Nesstique,” one of Ness’s most popular show machines, is a good example of the Bay Area concept: spare, graceful, surgically clean of line, its chromed Sportster engine resting within a chassis so spidery that the viewer is tempted to ask, “Where’s the rest of it?” A more recent example, “Blown Shovel,” which Ness built to resemble a brutally powerful, street-going dragbike, also has that lean-and-mean look, as do many other of his creations.

But while the Bay Area look favored the Sportster engine’s proportions, the latest trend is toward customs using Harley’s Big Twin engine. This family of powerplants is huge, embracing 74and 80-cubic-inch engines ranging from the knucklehead, first made in 1936, to today’s blockhead (the most popular nickname for Harley’s new Evolution engine) design.

When asked if there is any particular reason for this latest trend, Ness simply answers, “Naw, it’s just a fad.”

Yeah, sure. But what he’s not telling us is that he helped start the fad, such is his influence throughout the field.

Compared to his Sportsters, Ness’s Big Twin customs are strikingly different. Their style is exemplified by the hulking “Strictly Business,” an ex-dragbike powered by a 100-inch Big Twin engine. “This was my first bike with the ‘Big Look,’ ” Ness explains, “but I built it to be as light as possible.” As a result, this 10-second street fighter is fitted with many aluminum parts, including handmade fuel tanks, triple clamps, battery box and fender rails. The spun-aluminum Mitchell wheels have been drilled for lightness, then black-anodized and engraved.

But Ness’s masterpiece is “Two Bad,” a machine that qualifies as a motorcycle in the metaphysical sense as well

as in the physical sense. It has just two wheels, so, one supposes, that makes it a bike. But by virtue of its frontmounted supercharger, its four fuel tanks scattered about the chassis, its hub-center steering, and its 2000cc and four cylinders of Sportster powerplant, well, it challenges the term “motorcycle.” It’s a creation that Ness figures is worth more than $50,000.

When asked what prompted him to build such a thing, Ness The Non-Verbal just shrugs and says, “Oh, I don’t know. It’s just something I’d been thinking about for awhile.”

He was obsessed with the idea, in other words.

Oddly enough, one of his latest passions is not the building of new Nessbikes but the retrieval of older ones. The Oakland Museum has purchased one of his machines outright for display, and would like to buy another that it has on loan; and a few auto museums have expressed interest in acquiring some of his glittering hardware. This activity has prompted a run on any ex-Ness customs that might be floating around, causing their value to soar. But Ness doesn’t want to sell any of the machines he currently owns, and is intent on buying back those that he sold in years past. “I don’t build bikes for people,” he says, “and I never have. I just build them as prototypes and testbeds for other parts. And I always build one for the Oakland Roadster Show. But I’ve let some of them go,” he says ruefully, “and I want to get 'em back.”

“Just for nostalgia’s sake?” someone inquired.

“Well, yeah. That and the fact that I’ve been thinking about opening a museum of my own.”

You can bet he will. Remember his words: “Once I get started on something, that’s it!” E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialDown But Not Out

June 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeMoto-Immortality

June 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsAlas, Albion

June 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1988 -

Rondup

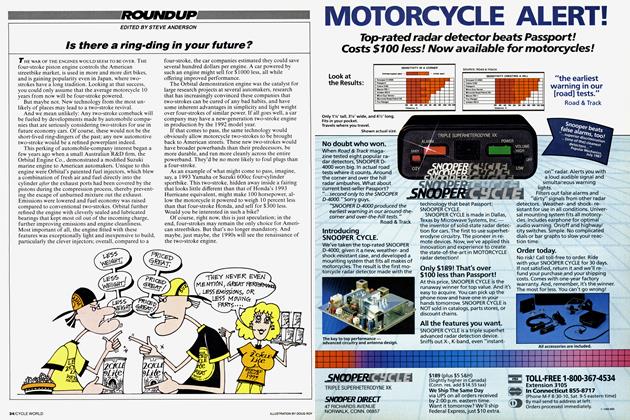

RondupIs There A Ring-Ding In Your Future?

June 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Rondup

RondupLetter From Japan

June 1988 By Kengo Yagawa