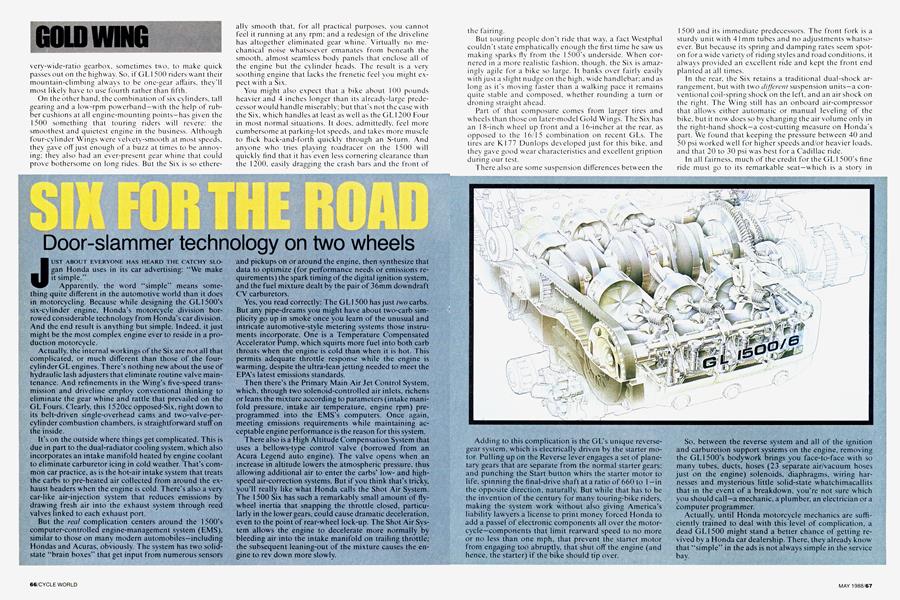

SIX FOR THE ROAD

Door-slammer technoloay on two wheels

JUST ABOUT EVERYONE HAS HEARD THE CATCHY SLOgan Honda uses in its car advertising: “We make it simple.”

Apparently, the word “simple” means something quite different in the automotive world than it does

in motorcycling. Because while designing the GL1500’s six-cylinder engine, Honda’s motorcycle division bor-

rowed considerable technology from Honda's car division.

And the end result is anything but simple. Indeed, it just

might be the most complex engine ever to reside in a pro-

duction motorcycle.

Actually, the internal workings of the Six are not all that

complicated, or much different than those of the four-

cylinder GL engines. There's nothing new about the use of

hydraulic lash adjusters that eliminate routine valve main-

tenance. And refinements in the Wing’s five-speed transmission and driveline employ conventional thinking to

eliminate the gear whine and rattle that prevailed on the

GL Fours. Clearly, this 1520cc opposed-Six, right down to

its belt-driven single-overhead cams and two-valve-per-

cylinder combustion chambers, is straightforward stuff on

the inside.

It’s on the outside where things get complicated. This is due in part to the dual-radiator cooling system, which also

incorporates an intake manifold heated by engine coolant

to eliminate carburetor icing in cold weather. That’s com-

mon car practice, as is the hot-air intake system that treats

the carbs to pre-heated air collected from around the ex-

haust headers when the engine is cold. There’s also a very

car-like air-injection system that reduces emissions by drawing fresh air into the exhaust system through reed

valves linked to each exhaust port.

But the real complication centers around the 1500’s

computer-controlled engine-management system (EMS), similar to those on many modern automobiles—including

Hondas and Acuras, obviously. The system has two solidstate “brain boxes” that get input from numerous sensors and pickups on or around the engine, then synthesize that data to optimize (for performance needs or emissions requirements) the spark timingof the digital ignition system,

and the fuel mixture dealt by the pair of 36mm downdraft CV carburetors.

Yes, you read correctly: The GLI500 has just two carbs. But any pipe-dreams you might have about two-carb sim-

plicity go up in smoke once you learn of the unusual and

intricate automotive-style metering systems those instru-

ments incorporate. One is a Temperature Compensated

Accelerator Pump, which squirts more fuel into both carb

throats when the engine is cold than when it is hot. This

permits adequate throttle response while the engine is

warming, despite the ultra-lean jetting needed to meet the

EPA’s latest emissions standards.

Then there’s the Primary Main Air Jet Control System, which, through two solenoid-controlled air inlets, richens

or leans the mixture according to parameters (intake mani-

fold pressure, intake air temperature, engine rpm) pre-

programmed into the EMS's computers. Once again,

meeting emissions requirements while maintaining ac-

ceptable engine performance is the reason for this system.

There also is a High Altitude Compensation System that uses a bellows-type control valve (borrowed from an

Acura Legend auto engine). The valve opens when an

increase in altitude lowers the atmospheric pressure, thus

allowing additional air to enter the carbs' lowand high-

speed air-correction systems. But if you think that’s tricky,

you’ll really like what Honda calls the Shot Air System,

The 1500 Six has such a remarkably small amount of flywheel inertia that snapping the throttle closed, particu-

larly in the lower gears, could cause dramatic deceleration,

even to the point of rear-wheel lock-up. The Shot Air Sys-

tern allows the engine to decelerate more normally by bleeding air into the intake manifold on trailing throttle;

the subsequent leaning-out of the mixture causes the engine to rev down more slowly.

Adding to this complication is the GL’s unique reversegear system, which is electrically driven by the starter motor. Pulling up on the Reverse lever engages a set of planetary gears that are separate from the normal starter gears; and punching the Start button whirs the starter motor to life, spinning the final-drive shaft at a ratio of 660 to l -in the opposite direction, naturally. But while that has to be the invention of the century for many touring-bike riders, making the system work without also giving America’s liability lawyers a license to print money forced Honda to add a passel of electronic components all over the motorcycle-components that limit rearward speed to no more or no less than one mph, that prevent the starter motor from engaging too abruptly, that shut off the engine (and hence, the starter) if the bike should tip over.

So, between the reverse system and all of the ignition and carburetion support systems on the engine, removing the GL 1500’s bodywork brings you face-to-face with so many tubes, ducts, hoses (23 separate air/vacuum hoses just on the engine) solenoids, diaphragms, wiring harnesses and mysterious little solid-state whatchimacallits that in the event of a breakdown, you’re not sure which you should call-a mechanic, a plumber, an electrician or a computer programmer.

Actually, until Honda motorcycle mechanics are sufficiently trained to deal with this level of complication, a dead GL1500 might stand a better chance of getting revived by a Honda car dealership. There, they already know that “simple” in the ads is not always simple in the service bay.