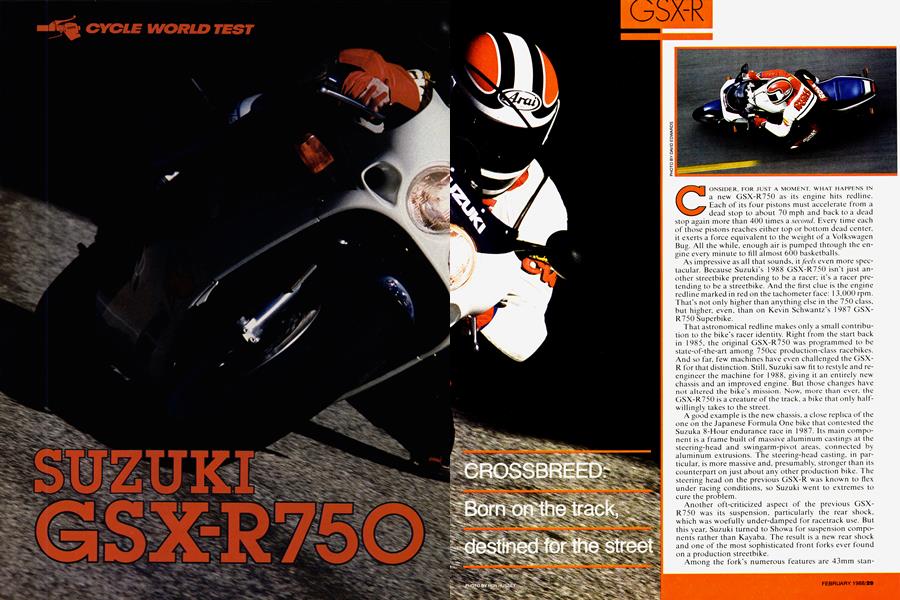

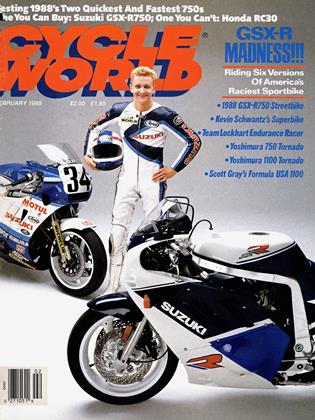

SUZUKI GSX-R750

CYCLE WORLD TEST

CROSSBREED: Born on the track, destined for the street

CONSIDER, FOR JUST A MOMENT, WHAT HAPPENS IN a new GSX-R750 as its engine hits redline. Each of its four pistons must accelerate from a dead stop to about 70 mph and back to a dead stop again more than 400 times a second. Every time each of those pistons reaches either top or bottom dead center, it exerts a force equivalent to the weight of a Volkswagen Bug. All the while, enough air is pumped through the engine every minute to fill almost 600 basketballs.

As impressive as all that sounds, it feels even more spectacular. Because Suzuki’s 1988 GSX-R750 isn’t just another streetbike pretending to be a racer; it’s a racer pretending to be a streetbike. And the first clue is the engine redline marked in red on the tachometer face; 1 3,000 rpm. That’s not only higher than anything else in the 750 class, but higher, even, than on Kevin Schwantz’s 1987 GSXR750 Superbike.

That astronomical redline makes only a small contribution to the bike’s racer identity. Right from the start back in 1985, the original GSX-R750 was programmed to be state-of-the-art among 750cc production-class racebikes. And so far, few machines have even challenged the GSXR for that distinction. Still, Suzuki saw fit to restyle and reengineer the machine for 1988, giving it an entirely new chassis and an improved engine. But those changes have not altered the bike’s mission. Now, more than ever, the GSX-R750 is a creature of the track, a bike that only halt -willingly takes to the street. A good example is the new chassis, a close replica of the one on the Japanese Formula One bike that contested the Suzuka 8-Hour endurance race in 1987. Its main component is a frame built of massive aluminum castings at the steering-head and swingarm-pivot areas, connected by aluminum extrusions. The steering-head casting, in particular, is more massive and, presumably, stronger than its counterpart on just about any other production bike. The steering head on the previous GSX-R was known to flex under racing conditions, so Suzuki went to extremes to cure the problem. Another oft-criticized aspect of the previous GSXR750 was its suspension, particularly the rear shock, which was woefully under-damped for racetrack use. But this year, Suzuki turned to Showa for suspension components rather than Kayaba. The result is a new rear shock and one of the most sophisticated front forks ever found on a production streetbike. Among the fork’s numerous features are 43mm stanchions, cartridge-type dampers that keep the air and oil from integrating, and independent adjustments for spring preload, rebound damping and compression damping. As on previous GSX-R750s, the rear shock is a non-reservoir unit with just four rebound-damping adjustments, but it works through a new linkage that provides more-progressive rear-wheel rates.

While Suzuki was on its search-and-destroy mission for flaws in the old GSX-R. the company decided to collaborate with Michelin and develop the new bike around 17inch radial tires. So, both ends use street tires that, in basic carcass construction, are almost identical to the racing radiais that dominated American Superbike competition and European GPs last season.

Being 1 7-inch tires as opposed to the 1 8-inchers on previous GSX-R750s, the Michelins make for a slightly lower motorcycle. What’s more, Suzuki also mounted the engine lower in the new chassis. And when you add to that the fact that the '88 bike has a shorter wheelbase (55 inches) and positions its handlebars closer to the rider, the end result is a smaller, more compact motorcycle.

Of course, the intent of all this lowering and compacting is to improve the 750’s cornering prowess. And it indeed does just that; flopping the Suzuki over into a turn is a downright effortless affair. The steering always is completely neutral, so the bike seems just as content when it’s tip-toeing around a low-speed hairpin as it does when it’s banked way over on its side and barrelling flat-out through a fast sweeper. Despite its love of corners, though, the bike is very stable when going dead-nuts straight, more so than its ’86-’87 predecessors.

But the quest for lowness has created a dilemma for the new GSX-R. Because even though the bike is clearly intended to be ridden racetrack-hard, it has very soft springing and less cornering clearance than any 75(3 sportbike in years. Consequently, when the bike is pushed fairly aggressively around the track, the kickstand hits the ground on the left, and the fairing drags on both sides—even if the rider hangs off'quite far. Worse yet, the new' 4-into-2 exhaust system bangs the pavement hard on both sides—hard enough to grind all the way through the collector pipes in a very short time.

With the preload cranked way up on both the fork and the shock, it’s unlikely that many sparks will fly under normal street use; but racers will have to perform some serious suspension modifications if they plan on campaigning an '88 GSX-R750. Even then, the bike will require a bit of chassis re-engineering before a shortage of ground clearance is no longer a serious problem.

For street-riding purposes, however, the suspension is excellent. With its universe of adjustability, the Suzuki can be made to handle anything from hard canyon riding to freeway droning. And even with so many adjustments to consider, it doesn't take much fiddling to get both ends set up and personalized.

Likewise, the brakes are superb, particularly the dual, floating front discs that are pinched by a pair of Nissin dual-piston calipers. The leading piston in each caliper is slightly smaller in diameter than its trailing counterpart, and that differential helps equalize the braking forces between the two pistons. These are basically the same calipers used on the Yoshimura racebikes; and anything that can consistently haul Kevin Schwantz down from 170 mph at Daytona is more than adequate for street use.

That’s not the only way in which the Suzuki shows its racing aspirations. Ergonomically, the GSX-R’s low seat, high pegs and full clip-on handlebars put its rider in a classic roadrace tuck. Granted, the bars are slightly closer to the rider than they were on the previous model, and higher in relation to the seat, as well; but a trip of any length, particularly a drone along the open road, still is quite painful. On top of that, the rider isn't well-insulated from engine heat. The fairing has two fresh-air intakes up front, but not for cooling the rider. One is an intake for the airbox, and the other funnels cool air to the area around the carburetors—a racebike-developed trick that allows a more-consistent carburetion.

But to complain about the lack of comfort is to miss the point: The GSX-R750 is a pure performer, a fact that’s obvious the first time the throttle is opened. This year, though, the engine is not just a screamer, but a decent torquer, too. A lot of street riders complained about the meek roll-on acceleration of the '86 and '87 models, so Suzuki sharpened up that aspect of performance, as well. The GSX-R still might not quite equal Honda’s VFR750 or Yamaha’s FZR750R for low-end and mid-range power, but it is worlds better than its predecessors.

Respectable performance, then, begins right at the bottom; and all the way from idle up to the howling, 13,000rpm crescendo, the power output increases linearly and with unwavering precision. At no point in the engine’s climb is there a surge or a dip in acceleration; there’s no discernable powerband. For every rpm the engine climbs, it produces one rpm's worth of added power, no more, no less. By the time it reaches thirteen grand it’s making a lot of power, and things are happening real fast.

One reason why the redline is so much higher than on last year’s engine is the 3.8mm-shorter stroke. In addition to reducing piston speed at peak rpm to an acceptable level, the destroking permitted a 3mm-larger bore; and that yields more power by allowing the same-size valves (28.5mm intakes and 25mm exhausts) as used on the GSX-R 1 100. Further concessions to mega-high rpm are found in the pistons: They have short, slipper-style skirts for light weight, and each uses two skinny, 0.8mm-thick compression rings to reduce friction.

Performance throughout the rpm range, not just at redline, has been sharpened by the ’88 GSX-R’s 36mm Mikuni “Slingshot” CV carburetors. The vacuum-operated slides in these carbs are flat in front and round in back, combining the smooth, almost uninterrupted throttle-bores allowed by flat-slide designs and the reduced intake-side air turbulence provided by round slides. The engine also employs a digital electronic spark advance that makes its own contribution to performance by more accurately controlling the precise moment of ignition.

Because higher power outputs bring with them added heat, the new engine uses an improved version of Suzuki’s exclusive oil-cooling system. For ’88, the oil-cooling pockets located above the combustion-chamber domes have been reshaped for more-efficient oil flow; and the system now uses a larger-capacity oil cooler that is bigger than the coolant radiators on many liquid-cooled bikes.

For various reasons, then, the 1988 GSX-R750 has a power output that is close to perfect, for both the racetrack and the street. But the chassis’ odd mix of excellence and compromise leaves the new GSX-R in a peculiar position. On the street, it is too narrowly focused to appeal to riders uninterested in the image-enhancing value of riding the ultimate street racer. And on the track, it is limited by a batfling engineering oversight, ensuring that its chances of winning, in stock form, at least, will quickly disappear in a shower of sparks from the undercarriage.

Still, in the upcoming year, the GSX-R750 will no doubt be the cornerstone of American Superbike racing, just as it has been for the past couple of years. Racers, by and large, are an inventive bunch rarely thwarted by problems so small as a lack of cornering clearance. So, the 1 988 GSX-R750 will flt into its competition role well. It will once again be the bike of choice for roadracers who need the ultimate in performance.

And in even greater numbers, the GSX-R will appeal to riders who aren't out to win a Superbike race. They just like the idea of owning a bike that could. Eâ

SUZUKI

GSX-R750

$5199

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsBad Raps And Bad Reps

FEBRUARY 1988 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsRaised Standards

FEBRUARY 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupNew Allies In the Atv Wars

FEBRUARY 1988 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

FEBRUARY 1988 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

FEBRUARY 1988 By Alan Cathcart