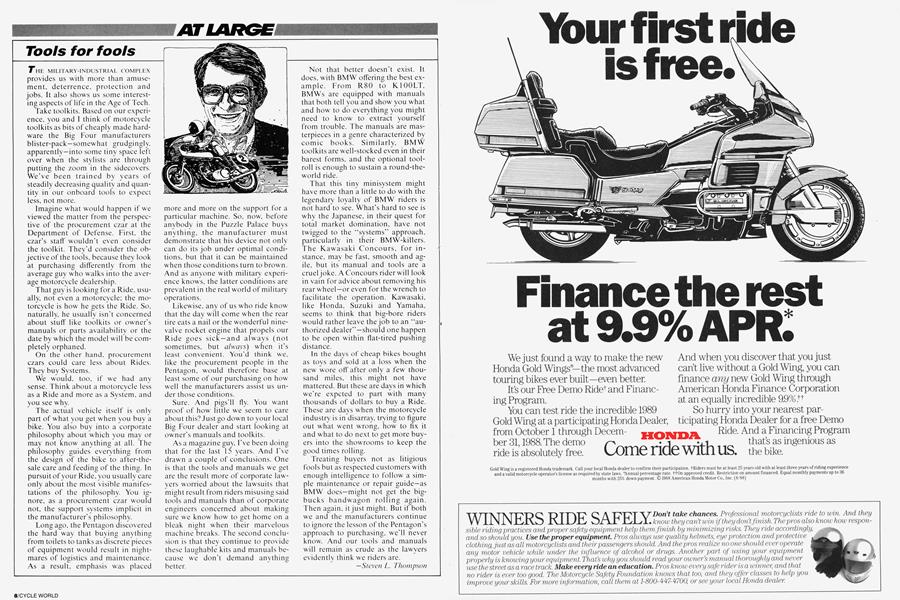

Tools for fools

AT LARGE

THE MILITARY-INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX

provides us with more than amusement, deterrence, protection and jobs. It also shows us some interesting aspects of life in the Age of Tech.

Take toolkits. Based on our experience, you and I think of motorcycle toolkits as bits of cheaply made hardware the Big Four manufacturers blister-pack—somewhat grudgingly, apparently—into some tiny space left over when the stylists are through putting the zoom in the sidecovers. We’ve been trained by years of steadily decreasing quality and quantity in our onboard tools to expect less, not more.

Imagine what would happen if we viewed the matter from the perspective of the procurement czar at the Depar3tment of Defense. First, the czar’s staff wouldn’t even consider the toolkit. They'd consider the objective of the tools, because they look at purchasing differently from the average guy who walks into the average motorcycle dealership.

That guy is looking for a Ride, usually, not even a motorcycle; the motorcycle is how he gets the Ride. So, naturally, he usually isn't concerned about stuff like toolkits or owner’s manuals or parts availability or the date by which the model will be completely orphaned.

On the other hand, procurement czars could care less about Rides. They buy Systems.

We would, too, if we had any sense. Think about a motorcycle less as a Ride and more as a System, and you see why.

The actual vehicle itself is only part of what you get when you buy a bike. You also buy into a corporate philosophy about which you may or may not know anything at all. The philosophy guides everything from the design of the bike to after-thesale care and feeding of the thing. In pursuit of your Ride, you usually care only about the most visible manifestations of the philosophy. You ignore, as a procurement czar would not, the support systems implicit in the manufacturer’s philosophy.

Long ago, the Pentagon discovered the hard way that buying anything from toilets to tanks as discrete pieces of equipment would result in nightmares of logistics and maintenance. As a result, emphasis was placed more and more on the support for a particular machine. So, now. before anybody in the Puzzle Palace buys anything, the manufacturer must demonstrate that his device not only can do its job under optimal conditions, but that it can be maintained when those conditions turn to brown. And as anyone with military experience knows, the latter conditions are prevalent in the real world of military operations.

Likewise, any of us who ride know that the day will come when the rear tire eats a nail or the wonderful ninevalve rocket engine that propels our Ride goes sick —and always (not sometimes, but always) when it’s least convenient. You’d think we, like the procurement people in the Pentagon, would therefore base at least some of our purchasing on how well the manufacturers assist us under those conditions.

Sure. And pigs’ll fly. You want proof of how little we seem to care about this? Just go down to your local Big Four dealer and start looking at owner’s manuals and toolkits.

As a magazine guy. I've been doing that for the last 15 years. And I've drawn a couple of conclusions. One is that the tools and manuals we get are the result more of corporate lawyers worried about the lawsuits that might result from riders misusing said tools and manuals than of corporate engineers concerned about making sure we know how to get home on a bleak night when their marvelous machine breaks. The second conclusion is that they continue to provide these laughable kits and manuals because we don't demand anything better.

Not that better doesn't exist. It does, with BMW offering the best example. From R80 to K100LT, BMWs are equipped with manuals that both tell you and show you what and how to do everything you might need to know to extract yourself from trouble. The manuals are masterpieces in a genre characterized by comic books. Similarly, BMW toolkits are well-stocked even in their barest forms, and the optional toolroll is enough to sustain a round-theworld ride.

That this tiny minisystem might have more than a little to do with the legendary loyalty of BMW riders is not hard to see. What’s hard to see is why the Japanese, in their quest for total market domination, have not twigged to the “systems” approach, particularly in their BMW-killers. The Kawasaki Concours, for instance. may be fast, smooth and agile, but its manual and tools are a cruel joke. A Concours rider will look in vain for advice about removing his rear wheel—or even for the wrench to facilitate the operation. Kawasaki, like Honda, Suzuki and Yamaha, seems to think that big-bore riders would rather leave the job to an “authorized dealer”—should one happen to be open within flat-tired pushing distance.

In the days of cheap bikes bought as toys and sold at a loss when the new wore off after only a few thousand miles, this might not have mattered. But these are days in which we're expcted to part with many thousands of dollars to buy a Ride. These are days when the motorcycle industry is in disarray, trying to figure out what went wrong, how to fix it and what to do next to get more buyers into the showrooms to keep the good times rolling.

Treating buyers not as litigious fools but as respected customers with enough intelligence to follow a simple maintenance or repair guide—as BMW does—might not get the bigbucks bandwagon rolling again. Then again, it just might. But if both we and the manufacturers continue to ignore the lesson of the Pentagon’s approach to purchasing, we'll never know. And our tools and manuals will remain as crude as the lawyers evidently think we riders are.

Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue