The high cost of plastic

ROUNDUP

STEVE ANDERSON

DURING LAST MONTH’S l000cc STREETBIKE COMPARISON, WE

had an encounter with one of motorcycling’s less-pleasant realities. Of the eight bikes we rode for the test, three got dropped. The FZR1000 suffered a zero-speed tipover in a gas station; the Hurricane was subjected to a LaughIn-style fall while making a U-turn during a photo session; and the ZX-10 went down at about 20 mph when its rider hit some gravel while braking.

No one was hurt, so the incidents were mostly embarrassing.

And expensive.

In all three cases, relatively minor mistakes were made major by the damage done to plastic bodywork; our parts bill alone for those three crashes would have been about $2500 if scratched and broken body pieces were replaced with new factory ones. Just the major plastic parts that constitute a Hurricane 1000 fairing cost $ 1 1 84; for a ZX-10, the total is $ 1133; for the FZR, $957.

Combine that kind of cost with the fairings’ relative fragility, and you have a serious problem for motorcycling. Almost any of the current plastic-encased sportbikes can suffer hundreds of dollars in damage just by rolling off its sidestand in the garage. And even a lowspeed crash can be a financial trauma; we’ve talked to service managers who’ve recounted how they’ve had to total motorcycles that were mechanically sound because of extensive cosmetic damage. The final irony may be seen at club-level roadraces, where you can find Hurricanes and Suzuki GSX-Rs running with most of their racy fairings removed. The reason: Their riders couldn’t afford to replace those parts if they crashed.

We suspect, too, that the insurance industry’s recent campaign against sportbikes may be as much related to plastic body parts as to high crash rates. In the past, if you tipped over a Z-1 or a CB750 in a garage, you might break a clutch lever or mirror, and perhaps scratch a sidecover or exhaust pipe—relatively minor damage, and nothing that would result in an insurance claim. Do the same to a Ninja, and smash body panels and bend fairing supports, and you’re suddenly over your deductible. The consequence is that insurance companies get increased claims for sportbikes, resulting in coverage for these motorcycles that is more expensive and difficult to obtain.

This high repair-cost problem is significant enough that the industry needs to seek solutions. There are many possibilities, such as offering motorcycles without fairings; Honda’s Hawk is a step in that direction. In Japan, the raciest sportbikes are often offered both with and without fairings. Interestingly enough, it’s the models without bodywork that are popular with Japanese club racers.

Another approach would be to make fairings more resistant to minor tip-overs or crashes. The 600cc Ninjas used by Keith Code’s California Superbike School now wear bolt-on nylon pads at the points where their fairings would normally contact the ground; Code reports that in a slide-out-type crash, these can be very effective in preventing fairing damage. Honda’s 1000 Hurricane has mirrors that can spring out of the way in a tip-over, saving the upper fairing from being levered to bits. Applying this type of thought to fairing design could lead to further improvements.

Finally, manufacturers and dealers could do more to make minor fairing damage repairable. The manufacturers could offer plastic welding equipment and advice, as well as decal and stripe kits so plastic parts could be repainted and restored to their original condition. At least some dealers could specialize in repairing and repainting these plastic parts instead of simply replacing them at substantial expense.

In the end. though, the motorcycle industry needs to take a hard look at the current trend toward totally enclosed sportbikes. Right now. these machines are too expensive to buy and repair, and not easy to insure. And that will have to change.

1989 Harley-Davidsons

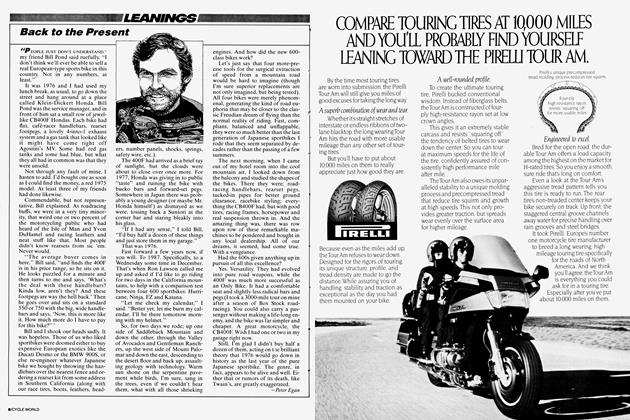

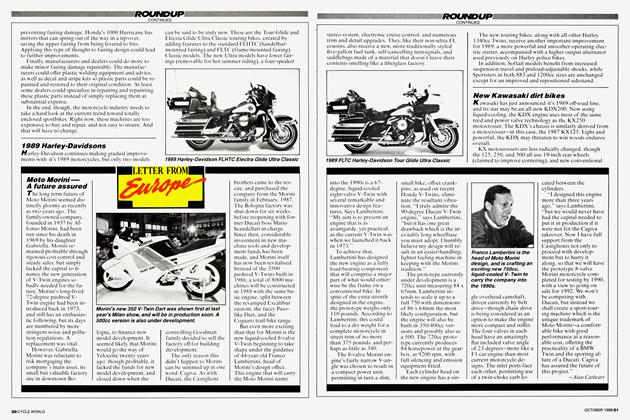

Harley-Davidson continues making gradual improvements with it’s 1989 motorcycles, but only two models

can be said to be truly new'. These are the Tour Glide and Electra Glide Ultra Classic touring bikes, created by adding features to the standard FLHTC (handelbarmounted fairing) and FLTC (frame-mounted fairing) Classic models. The new Ultra models have lower fairings (removable for hot summer riding), a four-speaker stereo system, electronic cruise control, and numerous trim and detail upgrades. They, like their non-ultra FL cousins, also receive a new, more-traditionally styled five-gallon fuel tank, self-cancelling turnsignals, and saddlebags made of a material that doesn't leave their contents smelling like a fiberglass factory.

1989 FLTC Harley-Davidson Tour Glide Ultra Classic

The new touring bikes, along with all other Harley 1340cc Twins, receive another important improvement for l 989: a more powerful and smoother-operating electric starter, accompanied with a higher output alternator used previously on Harley police bikes.

In addition, Softail models benefit from increased suspension travel and preload-adjustable shocks, while Sportsters in both 883 and 1200cc sizes are unchanged except for an improved and repositioned sidestand.

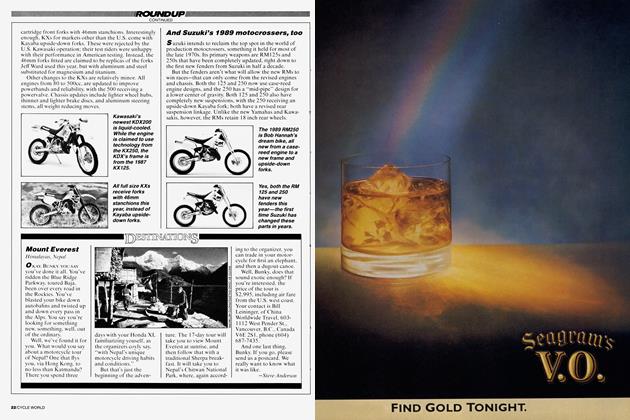

New Kawasaki dirt bikes

ICawasaki has just announced it’s 1989 off-road line, and its star may be an all new KDX200. Now using liquid-cooling, the KDX engine uses most of the same reed and power valve technology as the KX250 motocrosser. The KDX’s chassis is similarly derived from a motocrosser—in this case, the 1987 KX 125. Fight and powerful, the KDX may threaten to win woods enduros overall.

KX motocrossers are less radically changed, though the 125, 250, and 500 all use l 9-inch rear wheels (claimed to improve cornering), and new conventional cartridge f'ront forks with 46mm stanchions. Interestingly enough. KXs for markets other than the U.S. come with Kayaba upside-down forks. These were rejected by the U.S. Kawasaki operation; their test riders were unhappy with their performance in American testing. Instead, the 46mm forks fitted are claimed to be replicas of the forks Jell'Ward used this year, but with aluminum and steel substituted for magnesium and titanium.

Other changes to the KXs are relatively minor. All engines from 80 to 500cc, are updated to improve powerbands and reliability, with the 500 receiving a powervalve. Chassis updates include lighter wheel hubs, thinner and lighter brake discs, and aluminum steering stems, all weight reducing moves.

And Suzuki’s 1989 motocrossers, too

Suzuki intends to reclaim the top spot in the world of production motocrossers, something it held for most of the late 1970s. Its primary weapons are RM 125s and 250s that have been completely updated, right down to the first new fenders from Suzuki in half a decade.

But the fenders aren’t what will allow the new RMs to win races—that can only come from the revised engines and chassis. Both the 125 and 250 now use case-reed engine designs, and the 250 has a “mid-pipe” design for a lower center of gravity. Both 125 and 250 also have completely new suspensions, with the 250 receiving an upside-down Kayaba fork; both have a revised rear suspension linkage. Unlike the new Yamahas and Kawasakis, however, the RMs retain 18 inch rear wheels.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue