BMW PARALEVER

Taming the elevator syndrome

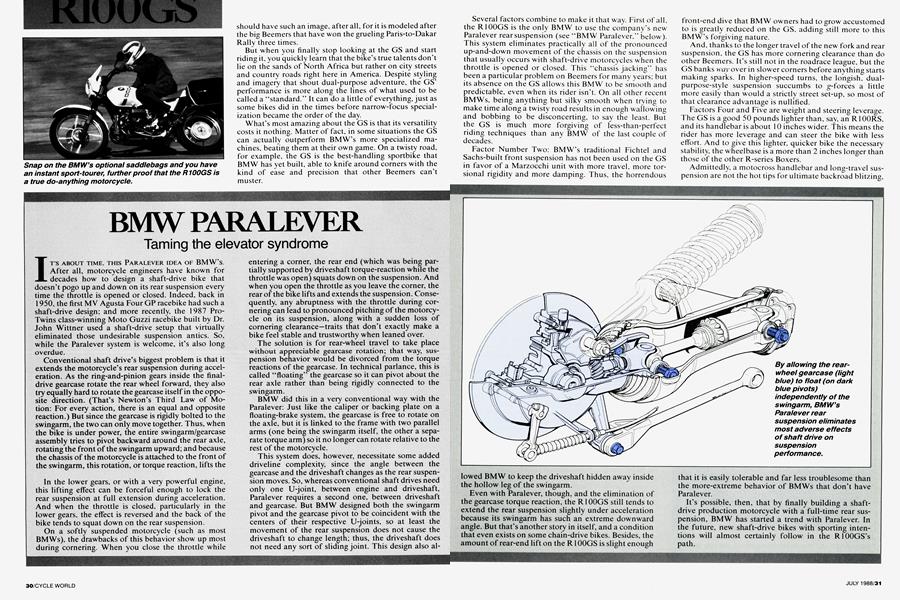

IT'S ABOUT TIME. THIS PARALEVER IDEA OF BMW's. After all, motorcycle engineers have known for decades how to design a shaft-drive bike that doesn't pogo up and down on its rear suspension every time the throttle is opened or closed. Indeed, back in 1950, the first MV Agusta Four GP racebike had such a shaft-drive design; and more recently, the 1987 Pro-Twins class-winning Moto Guzzi racebike built by Dr. John Wittner used a shaft-drive setup that virtually eliminated those undesirable suspension antics. So, while the Paralever system is welcome, it's also long overdue.

Conventional shaft drive’s biggest problem is that it extends the motorcycle’s rear suspension during acceleration. As the ring-and-pinion gears inside the finaldrive gearcase rotate the rear wheel forward, they also try equally hard to rotate the gearcase itself in the opposite direction. (That’s Newton’s Third Law of Motion: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.) But since the gearcase is rigidly bolted to the swingarm, the two can only move together. Thus, when the bike is under power, the entire swingarm/gearcase assembly tries to pivot backward around the rear axle, rotating the front of the swingarm upward; and because the chassis of the motorcycle is attached to the front of the swingarm, this rotation, or torque reaction, lifts the

In the lower gears, or with a very powerful engine, this lifting effect can be forceful enough to lock the rear suspension at full extension during acceleration. And when the throttle is closed, particularly in the lower gears, the effect is reversed and the back of the bike tends to squat down on the rear suspension.

On a softly suspended motorcycle (such as most BMWs), the drawbacks of this behavior show up most during cornering. When you close the throttle while

entering a corner, the rear end (which was being partially supported by driveshaft torque-reaction while the throttle was open) squats down on the suspension. And when you open the throttle as you leave the corner, the rear of the bike lifts and extends the suspension. Consequently, any abruptness with the throttle during cornering can lead to pronounced pitching of the motorcycle on its suspension, along with a sudden loss of cornering clearance—traits that don’t exactly make a bike feel stable and trustworthy when leaned over.

The solution is for rear-wheel travel to take place without appreciable gearcase rotation; that way, suspension behavior would be divorced from the torque reactions of the gearcase. In technical parlance, this is called “floating” the gearcase so it can pivot about the rear axle rather than being rigidly connected to the swingarm.

BMW did this in a very conventional way with the Paralever: Just like the caliper or backing plate on a floating-brake system, the gearcase is free to rotate on the axle, but it is linked to the frame with two parallel arms (one being the swingarm itself, the other a separate torque arm) so it no longer can rotate relative to the rest of the motorcycle.

This system does, however, necessitate some added driveline complexity, since the angle between the gearcase and the driveshaft changes as the rear suspension moves. So, whereas conventional shaft drives need only one U-joint, between engine and driveshaft, Paralever requires a second one, between driveshaft and gearcase. But BMW designed both the swingarm pivot and the gearcase pivot to be coincident with the centers of their respective U-joints, so at least the movement of the rear suspension does not cause the driveshaft to change length; thus, the driveshaft does not need any sort of sliding joint. This design also al-

lowed BMW to keep the driveshaft hidden away inside the hollow leg of the swingarm.

Even with Paralever, though, and the elimination of the gearcase torque reaction, the R100GS still tends to extend the rear suspension slightly under acceleration because its swingarm has such an extreme downward angle. But that’s another story in itself, and a condition that even exists on some chain-drive bikes. Besides, the amount of rear-end lift on the R100GS is slight enough

that it is easily tolerable and far less troublesome than the more-extreme behavior of BMWs that don’t have Paralever.

It’s possible, then, that by finally building a shaftdrive production motorcycle with a full-time rear suspension, BMW has started a trend with Paralever. In the future, new shaft-drive bikes with sporting intentions will almost certainly follow in the RIOOGS’s path.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialAmerican Racewatching's Finest Hour

July 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeBad Day In Daly City

July 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsRadio Daze

July 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupSafer Cycling Through Electronics

July 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

July 1988 By Alan Cathcart