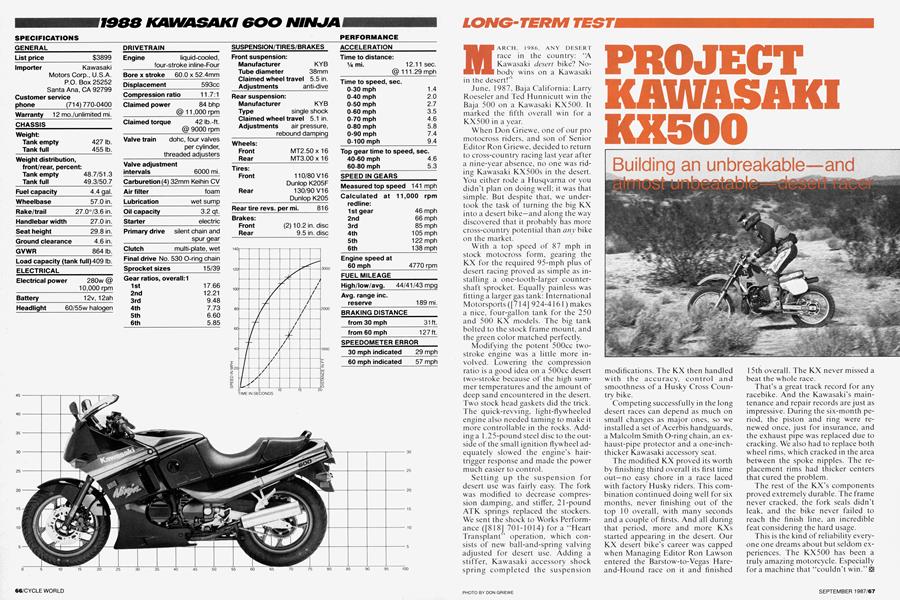

PROJECT KAWASAKI KX500

LONG-TERM TEST

Building an unbreakable—and almost unbeatable—desert racer

MARCH. 1986, ANY DESERT race in the country: "A Kawasaki desert bike? Nobody wins on a Kawasaki in the desert!”

June, 1987, Baja California: Larry Roeseler and Ted Hunnicutt win the Baja 500 on a Kawasaki KX500. It marked the fifth overall win for a KX500 in a year.

When Don Griewe, one of our pro motocross riders, and son of Senior Editor Ron Griewe, decided to return to cross-country racing last year after a nine-year absence, no one was riding Kawasaki KX500s in the desert. You either rode a Husqvarna or you didn’t plan on doing well: it was that simple. But despite that, we undertook the task of turning the big KX into a desert bike—and along the way discovered that it probably has more cross-country potential than any bike on the market.

With a top speed of 87 mph in stock motocross form, gearing the KX for the required 95-mph plus of desert racing proved as simple as installing a one-tooth-larger countershaft sprocket. Equally painless was fitting a larger gas tank: International Motorsports ([714] 924-4161) makes a nice, four-gallon tank for the 250 and 500 KX models. The big tank bolted to the stock frame mount, and the green color matched perfectly.

Modifying the potent 500cc twostroke engine was a little more involved. Lowering the compression ratio is a good idea on a 500cc desert two-stroke because of the high summer temperatures and the amount of deep sand encountered in the desert. Two stock head gaskets did the trick. The quick-revving, light-flywheeled engine also needed taming to make it more controllable in the rocks. Adding a 1.25-pound steel disc to the outside of the small ignition flywheel adequately slowed the engine’s hairtrigger response and made the power much easier to control.

Setting up the suspension for desert use was fairly easy. The fork was modified to decrease compression damping, and stifler, 21-pound ATK springs replaced the Stockers. We sent the shock to Works Performance ([818] 701-1014) for a “Heart Transplant” operation, which consists of new ball-and-spring valving adjusted for desert use. Adding a stiffer, Kawasaki accessory shock spring completed the suspension modifications. The KX then handled with the accuracy, control and smoothness of a Husky Cross Country bike.

Competing successfully in the long desert races can depend as much on small changes as major ones, so we installed a set of Acerbis handguards, a Malcolm Smith O-ring chain, an exhaust-pipe protector and a one-inchthicker Kawasaki accessory seat.

The modified KX proved its worth by finishing third overall its first time out—no easy chore in a race laced with factory Husky riders. This combination continued doing well for six months, never finishing out of the top 10 overall, with many seconds and a couple of firsts. And all during that period, more and more KXs started appearing in the desert. Our KX desert bike’s career was capped when Managing Editor Ron Lawson entered the Barstow-to-Vegas Hareand-Hound race on it and finished 1 5th overall. The KX never missed a beat the whole race.

That’s a great track record for any racebike. And the Kawasaki’s maintenance and repair records are just as impressive. During the six-month period, the piston and ring were renewed once, just for insurance, and the exhaust pipe was replaced due to cracking. We also had to replace both wheel rims, which cracked in the area between the spoke nipples. The replacement rims had thicker centers that cured the problem.

The rest of the KX’s components proved extremely durable. The frame never cracked, the fork seals didn’t leak, and the bike never failed to reach the finish line, an incredible feat considering the hard usage.

This is the kind of reliability everyone one dreams about but seldom experiences. The KX500 has been a truly amazing motorcycle. Especially for a machine that “couldn’t win.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe High Cost of Higher Performance

September 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeCoached To Success

September 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1987 -

Evaluation

Evaluation"The Care And Feeding of Your Motorcycle"

September 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupGrass-Roots Saviors?

September 1987 By Charles Everitt -

Roundup

RoundupShort Subjects

September 1987