KAWASAKI KX250

CYCLE WORLD TEST

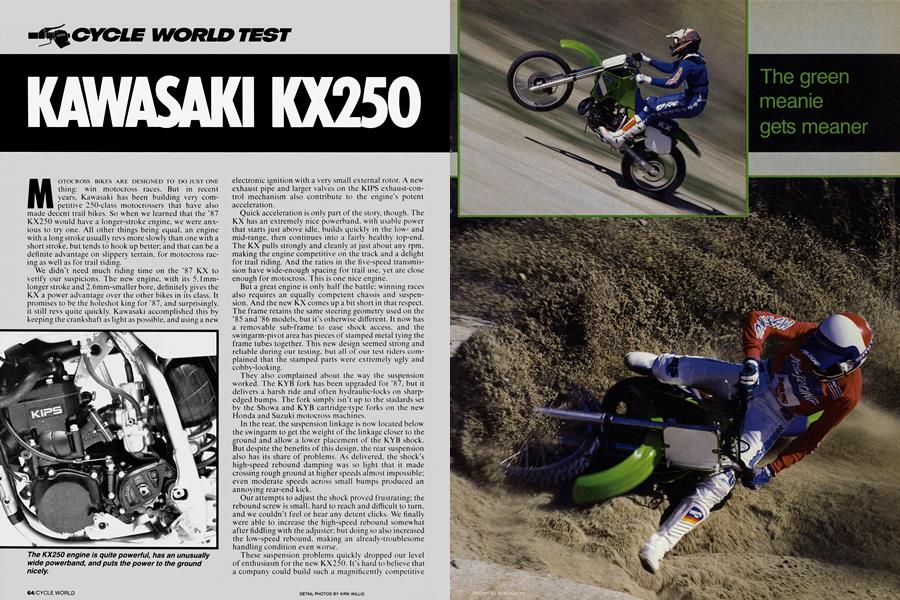

MOTOCROSS BIKES ARE DESIGNED TO DO JUST ONE thing: win motocross races. But in recent years, Kawasaki has been building very competitive 250-class motocrossers that have also made decent trail bikes. So when we learned that the '87 KX250 would have a longer-stroke engine, we were anxious to try one. All other things being equal. an engine with a long stroke usually revs more slowly than one with a short stroke, but tends to hook up better; and that can be a definite advantage on slippery terrain, for motocross racing as well as for trail riding.

We didn't need much riding time on the `87 KX to verify our suspicions. The new engine, with its 5. 1 mm longer stroke and 2.6mm-smaller bore, definitely gives the KX a power advantage over the other bikes in its class. It promises to be the holeshot king for `87, and surprisingly, it still revs quite quickly. Kawasaki accomplished this by keeping the crankshaft as light as possible, and using a new electronic ignition with a very small external rotor. A new exhaust pipe and larger valves on the KIPS exhaust-con trol mechanism also contribute to the engine's potent acceleration.

Quick acceleration is only part of the story. though. The KX has an extremely nice powerband. with usable power that starts just above idle, builds quickly in the lowand mid-range, then continues into a fairly healthy top-end. The KX pulls strongly and cleanly at just about any rpm, making the engine competitive on the track and a delight for trail riding. And the ratios in the five-speed transmis sion have wide-enough spacing for trail use, yet are close enough for motocross. This is one nice engine.

But a great engine is only halt tile battle: winning races also requires an equally competent chassis and suspen sion. And the new KX comes up a bit short in that respect. The frame retains the same steering geometry used on the `85 and `86 models, but it's otherwise different. It now has a removable sub-frame to ease shock access, and the swingarm-pivot area has pieces of stamped metal tying the frame tubes together. This new design seemed strong and reliable during our testing. but all of our test riders com plained that the stamped parts were extremely ugly and cobby-looking.

They also omplained about the way the suspension worked. The KYB fork has been upgraded for `87, but it delivers a harsh ride and often hydraulic-locks on sharp edged bumps. The fork simply isn't up to the stadards set by the Showa and KYB cartridge-type forks on the new Honda and Suzuki motocross machines.

In the rear, the suspension linkage is now located below the swingarm to get the weight of the linkage closer to the ground and allow a lower placement of the KYB shock. But despite the benefits of this design. the rear suspension also has its share of problems. As delivered, the shock's high-speed rebound damping was so light that it made crossing rough ground at higher speeds almost impossible; even moderate speeds across small bumps produced an annoying rear-end kick.

Ou~r ai~empts to adjust the shock proved frustrating; the rebound screw is small, hard to reach and difficult to turn. and we couldn't feel or hear any detent clicks. We finally were able to increase the high-speed rebound somewhat after fiddling with the adjuster: but doing so also increased the low-speed rebound, making an already-troublesome handling condition even worse.

Thes~ suspension problems quickly dropped our level of enthusiasm for the new KX250. It~s hard to believe that a company could build such a magnificently competitive engine and frame and then fit it with an ¿/¿¿competitive suspension. And if you’re a potential buyer who likes to trail ride between races, you won't be pleased to learn that the KX now comes with a tiny, 1.8-gallon gas tank. Naturally, the tank is skinny and unobtrusive, but it’s just barely big enough for motocross and a real drawback for just about any other kind of riding.

The green meanie gets meaner

These shortcomings are especially annoying, given the quality of the rest of the KX. It has excellent disc brakes at both wheels; the seat is narrow but comfortable due to a thoughtful shape and just the right foam density; the control levers and foot controls are easy to operate and properly placed; and the bike feels light and agile. There also is no doubt about the engine being competitive; our test KX250 whipped every 1987-model 250cc motocross bike in our shop when we drag-raced them all on smooth ground. The KX even turns easily and tracks accurately through the corners—as long as the track is smooth

But the problem is that motocross races aren’t held on smooth ground. And on typically rough, choppy motocross terrain, the ’87 KX250 can be just enough of a handful to prevent it from running wheel-to-wheel with most of the other bikes in its class.

Maybe the problem is that our test bike was not a representative example of the new KX250. Maybe we were unlucky enough to get one with suspension components that weren’t quite up to par. We’ll look into that possibility and let you know if our test unit was not typical of the breed.

But if it was, if everyone who is considering buying a 1987 KX250—either for motocross or for play riding—can expect to get the same kind of suspension performance we experienced, we have only two pieces of advice: either plan on coughing up a few hundred more dollars for suspension modifications, or spend your green on something red or yellow. 0

KAWASAKI KX250

$2899

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialA Crash Course In Career Counseling

June 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

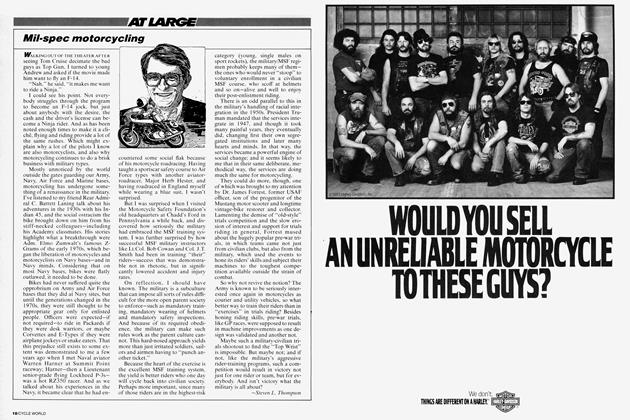

At LargeMil-Spec Motorcycling

June 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Shape of Things To Come

June 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

June 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

June 1987 By Alan Cathcart