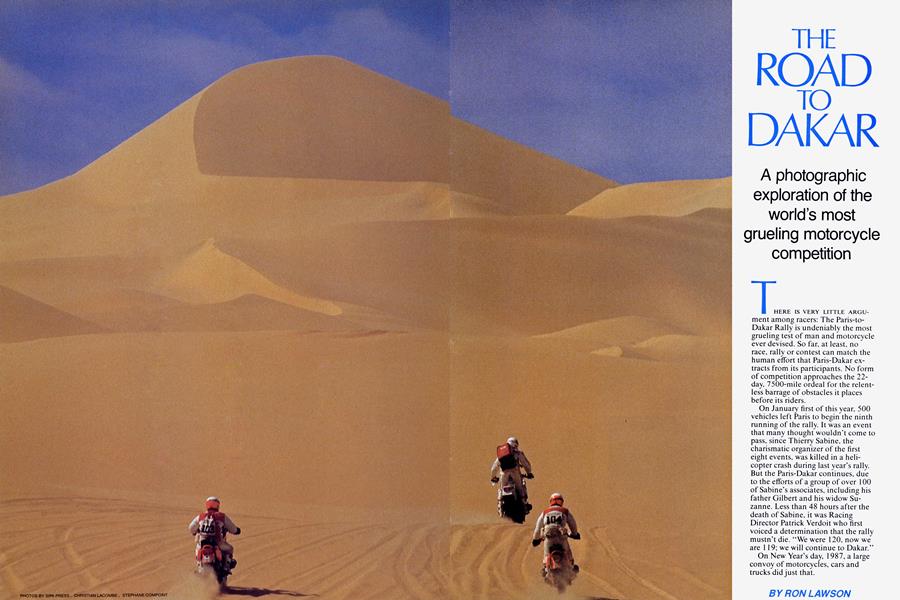

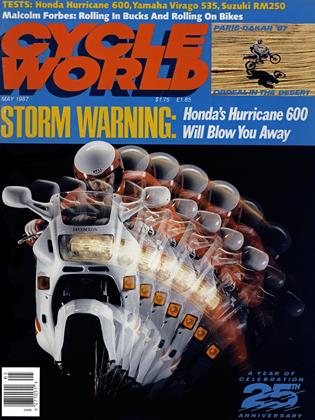

THE ROAD TO DAKAR

A photographic exploration of the world's most grueling motorcycle corn petition

THERE IS VERY LITTLE ARGU ment among racers: The Paris-to Dakar Rally is undeniably the most grueling test of man and motorcycle ever devised. So far, at least, no race, rally or contest can match the human effort that Paris-Dakar ex tracts from its participants. No form of competition approaches the 22day, 7500-mile ordeal for the relent less barrage of obstacles it places before its riders.

On January first of this year, 500 vehicles left Paris to begin the ninth running of the rally. It was an event that many thought wouldn't come to pass, since Thierry Sabine, the charismatic organizer of the first eight events, was killed in a heli copter crash during last year's rally. But the Paris-Dakar continues, due to the efforts of a group of over 100 of Sabine's associates, including his father Gilbert and his widow Su zanne. Less than 48 hours after the death of Sabine, it was Racing Director Patrick Verdoit who first voiced a determination that the rally mustn't die. "We were 120, now we are 11 9; we will continue to Dakar."

On New Year's day, 1987, a large convoy of motorcycles, cars and trucks did just that.

RON LAWSON

o * ^ ut in the sea of sand that is northern Africa, a man must reach inside and search for the special qualities it takes to overcome the desert, the distance and the other riders. Only an elite handful of men have found such qualities. The win list has but three names on it: Cyril Neveu, pictured above, who won this year as well as four other times; two-time winner Gaston Rahier (left); and twotimer Hubert Auriol. Even though three of Neveu’s earlier wins came aboard single-cylinder machines, all three men rode massive twin-cylinder motorcycles this year. Neveu was on the Honda NXR750 V-Twin, Rahier was on a lOOOcc BMW opposed-Twin, and Auriol on Cagiva’s upstart 850cc V-Twin, the Ducatiengined Elefant.

With the rally consisting of many sections where a rider can easily maintain over 100 mph, horsepower has become a key element in winning. Second only to endurance.

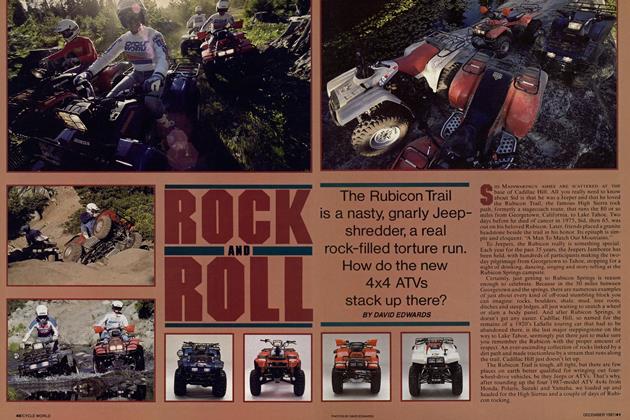

n the beginning, bikes and cars ran against each other in the Paris-Dakar rally. The bikes always won. It wasn’t until the third year of the rally that separate classes were formed for bikes, trucks and cars. Essentially, the different vehicles now run concurrent races over the same terrain.

Of the 7500 miles that make up the course, 2500 of them are transfer miles, places where the riders aren’t required to ride as hard as possible. The rest is special-test mileage, where the race’s outcome is decided.

Virtually all of the event, though, is through territory that most Americans would find totally alien, in both terrain and culture. In fact, the only American to finish the Paris-Dakar is the late Chuck Stearns, who finished seventh in 1984. As Stearns was later quoted in a CYCLE NEWS interview, “I think riding Paris-Dakar is the ultimate off-road experience.”

nothing you can count on, nothing you can predict. Hubert Auriol knew this going into the next-to-last day of the rally, but at that point, his lead over second-place Cyril Neveu seemed insurmountable. It would take a major catastrophe to keep him from taking his third victory, the first for Cagiva.

The major catastrophe happened in that day’s last “special test,” a section of terrain where a rider is to race as hard as possible against the clock. “I was following Neveu, but I swung out too wide on a curve,” Auriol related. “In the brush a root caught my right foot and threw me into a tree.” Auriol crashed hard, sustaining two broken ankles—one of them a compound fracture.

Suzuki rider Marc Joieau then arrived on the scene, and caring little about his own race, got Auriol back on the bike. The Cagiva rider was technically still in the lead at the end of the day, but the pain was too intense. His ride was over. In a tearful farewell. Neveu grasped Auriol’s hand as medics loaded the stricken rider into a helicopter. “Cyril is a great rider. I am glad it is he who will win,” Auriol said. “He was a fantastic adversary.”

he desert seems endless, and the riders have little more than compass readings leading them ultimately to Dakar. Only a few riders ever make it; this year, less than 20 percent completed the ordeal. For the rest, the rally can end in anything from a few minutes’ walk to the pits, or days of waiting in the dunes. Each rider carries an ARGOS beacon that sends out a signal to a satellite, allowing him to be found no matter how far he has strayed from the course. For many, that beacon is their only link to humanity.

Others find their hopes exploding in flames. Because of the great distances involved, the fuel capacity of the motorcycles is enormous, typically around 16 gallons. Thus, fires are an ever-present danger. One rider. Prescheur of the high-tech Ecureuil team, could only watch as his chances went up in Kevlar and carbon-fiber smoke. ga

View Full Issue

View Full Issue