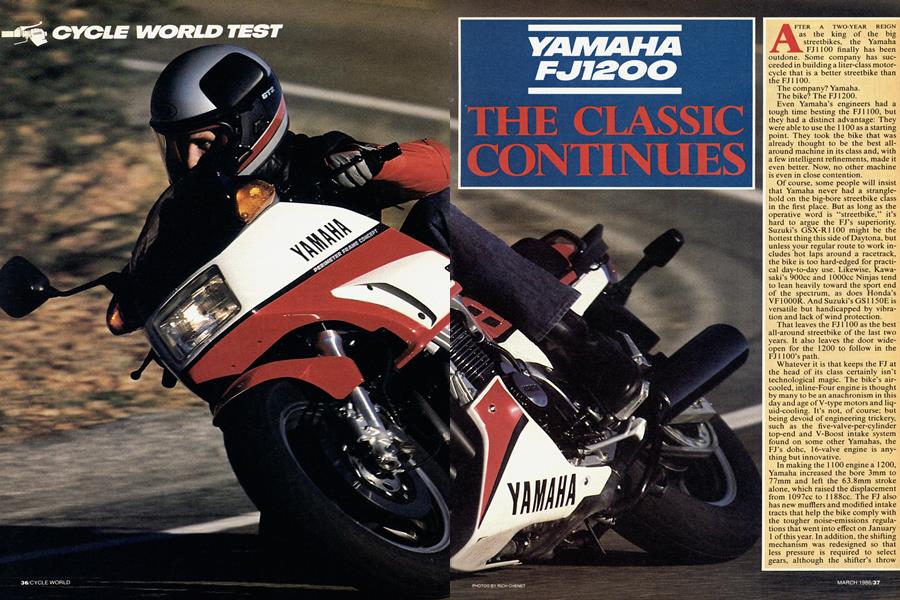

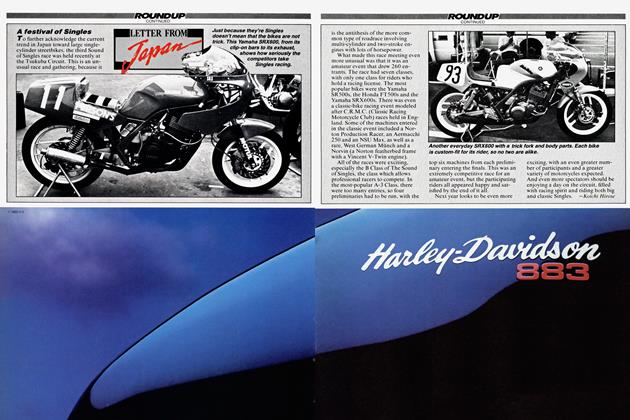

CYCLE WORLD TEST

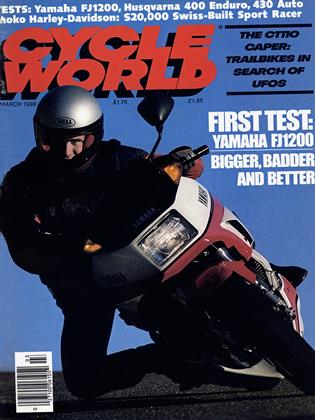

YAMAHA FJ1200

THE CLASSIC CONTINUES

AFTER A TWO-YEAR REIGN as the king of the big streetbikes, the Yamaha FJ1100 finally has been outdone. Some company has succeeded in building a liter-class motorcycle that is a better streetbike than the FJ1100.

The company? Yamaha.

The bike? The FJ1200.

Even Yamaha’s engineers had a tough time besting the FJ1100, but they had a distinct advantage: They were able to use the 1100 as a starting point. They took the bike that was already thought to be the best allaround machine in its class and, with a few intelligent refinements, made it even better. Now, no other machine is even in close contention.

Of course, some people will insist that Yamaha never had a stranglehold on the big-bore streetbike class in the first place. But as long as the operative word is “streetbike,” it’s hard to argue the FJ’s superiority. Suzuki’s GSX-R1100 might be the hottest thing this side of Daytona, but unless your regular route to work includes hot laps around a racetrack, the bike is too hard-edged for practical day-to-day use. Likewise, Kawasaki’s 900cc and lOOOcc Ninjas tend to lean heavily toward the sport end of the spectrum, as does Honda’s VF 1000R. And Suzuki’s GS 1150E is versatile but handicapped by vibration and lack of wind protection.

That leaves the FJ 1100 as the best all-around streetbike of the last two years. It also leaves the door wideopen for the 1200 to follow in the FJ1100’s path.

Whatever it is that keeps the FJ at the head of its class certainly isn’t technological magic. The bike’s aircooled, inline-Four engine is thought by many to be an anachronism in this day and age of V-type motors and liquid-cooling. It’s not, of course; but being devoid of engineering trickery, such as the five-valve-per-cylinder top-end and V-Boost intake system found on some other Yamahas, the FJ’s dohc, 16-valve engine is anything but innovative.

In making the 1100 engine a 1200, Yamaha increased the bore 3mm to 77mm and left the 63.8mm stroke alone, which raised the displacement from 1097cc to 1188cc. The FJ also has new mufflers and modified intake tracts that help the bike comply with the tougher noise-emissions regulations that went into effect on January 1 of this year. In addition, the shifting mechanism was redesigned so that less pressure is required to select gears, although the shifter’s throw was made slightly longer in the process. But other than those changes, the FJ 1200 engine is virtually identical to the FJ 1100 engine.

Indeed, rather than relying on pure technology, the FJ maintains its top ranking by being the most versatile and practical machine in its class, despite its decidedly roadracy appearance. The riding position, for instance, is a nice compromise, with the footpegs placed high enough so the canyon-crazies won’t easily touch them down on the street, yet low enough so that more-conservative riders won’t feel cramped. The same holds true for the handlebar position: It’s just low enough and far enough forward to make roadrace tucks and hanging-off easy, but still perfectly acceptable for hours of cruising on

the open road.

Actually, if those longer rides are of the sport-touring variety, the FJ is more than just acceptable; it’s virtually ideal. Perhaps a slightly wider and softer seat would be a measureable improvement, but the saddle is good by sportbike standards.

Much of the I200’s sport-touring competence can be traced to changes in the fairing that improve the way the bike parts the wind. The fairing looks almost the same as the 1100’s, but it is claimed to have a lower coefficient of drag due to being slightly narrower, having a lower and more raked-back windshield, and incorporating the turnsignals into the front of the fairing rather than on stalks at the sides. There’s also a higher and wider “chin” fairing down at the front of

the crankcases to smooth the flow of air around that part of the engine.

Odd as it may seem, the lower windshield actually affords the 1200 better wind protection than the 1100, in quality if not in quantity. The 1100’s more-vertical shield created quite a bit of turbulence that caused the rider to experience considerable buffeting around his helmet. The I200’s raked-back shield allows a cleaner flow of air over the top, which greatly reduces the turbulence. The lower shield does subject the rider to more airflow above neck level than the higher one, but that air is much less-turbulent and thus reduces buffeting. This is better “wind management,” as the tech guys like to call it, and it results in less rider-fatigue during long stints on the road.

Yamaha also claims that the new turnsignal location shields the rider’s hands from the elements; and to a certain extent it does. But it can't compare with the protection afforded by the fairing-mounted mirrors on the BMW KIOORS, arguably Europe’s best sport-touring machine. On the other hand, the I200’s mirrors do give you a superb view of what’s behind you, for Yamaha has moved them from the handlebars to the fairing and put them on long, aerodynamically shaped stalks. It’s not the raciest-looking mirror arrangement in the business, but it’s certainly one of the most useful.

Anyway, it isn’t just aerodynamics, wind protection or even comfort that makes the FJ the world’s most practical superbike; as much as anything else, it’s that “old” air-cooled motor. The 1200 certainly has awesome peak power, but it does much more than give the rider a head-rush in the quarter-mile. As low as 3000 rpm, the FJ starts pulling harder than most bikes can at any rpm. By the time it reaches five grand, the 1200 already is accelerating fast enough to pull your arms straight and make your eyes water—and you’re only about halfway through the wide powerband. From that point all the way up to the 9500-rpm redline, the FJ never lets up in the least.

What’s interesting is that Yamaha made no attempt to gain greater peak horsepower from the extra 9lcc, but instead used that added displacement to bolster the I200’s low-end and mid-range performance. The result is a bike that will go up against anything else on the road and flat eat it alive when it comes to roll-on acceleration. And that includes such streetgoing terrors as the 1150 Suzuki and the mighty V-Max. A few liter-class performance bikes might be faster in the quarter-mile and own a few more mph in top speed, but nothing can stay in the same vicinity with the FJ 1200 when the throttles are simply rolled open.

That roll-on prowess is one of the bike’s strongest assets on twisty backroads—and a prime reason why the FJ1200 is an even better sport-touring instrument than the FJ1100. A decent rider can go phenomenally fast on the FJ with a surprisingly small number of gear changesonce he develops a nice, smooth rhythm and utilizes the engine’s immense midrange torque. Any time you ride in this fashion over extended distances, you’re sport-touring, whether you know it or not. You can, of course, rev the engine to redline before every upshift in true sportbike fashion, and make every downshift where you would if you were on a racetrack; but aside from a lot more noise and considerably higher fuel consumption, you don’t gain much in terms of elapsed time from Point A to Point B.

That’s because the FJ1200 isn’t a hardcore sportbike. The 1100 was one when it was first introduced in 1984; but there are so many transplanted roadrace bikes available for the street these days that the FJ just isn’t quite competitive on a racetrack or whenever the road gets seriously twisty. In those situations, the Yamaha feels kind of cumbersome and uncooperative compared with GSX-Rs and Ninjas in particular. The 1200 can be ridden quite quickly through the swervery, but doing so requires more effort than those other bikes do.

Suspension-wise, the FJ again reflects that it’s intended for the road, not for the track. Front and rear, the spring and damping rates are soft, obviously intended more to deal with pavement joinings and potholes than to withstand the g-forces and violent

transitions normally associated with roadracing and ultra-serious backroad charging. Both the single-shock rear suspension and the front fork are adjustable for spring preload and rebound damping, but the stock settings didn’t cause any complaints among our test riders when it came to the bike’s primary missions—everyday riding, sport-touring and lessthan-full-berserk sport-riding.

Really, the only complaints we did have were mostly little things. The new bungie-cord hooks below the

sides of the seat, for example, are too high and far to the rear to be very useful. Also, the 1200’s new aircraftstyle gas cap is so close to the rear of the fuel tank that a tank bag (almost mandatory for sport-touring) must be altogether removed rather than just scooted back for refueling. On the other hand, the passenger grab-handles on both sides of the seat are a big improvement over the single grabbar on the 1 100. The inclusion of an LCD digital clock on the dashboard is something we think all manufacturers should do. And the FJ’s electrically activated fuel petcock has its On/Reserve switch mounted within easy reach on the fairing.

It’s little details like this, combined with big things such as the ever-ready power and real-world comfort, that allow the FJ1200 to follow in the FJ 1100’s footsteps as the king of the big streetbikes. It won’t win the technological wars, just as it’s not going to turn the fastest lap-times on a roadrace track or the quickest ETs at the local dragstrip. But for those who measure a motorcycle’s worth by the amount of pleasure it can deliver in a wide variety of riding circumstances, there’s not a better liter-class ride to be had anywhere. E3

YAMAHA

FJ1200

$5049

View Full Issue

View Full Issue