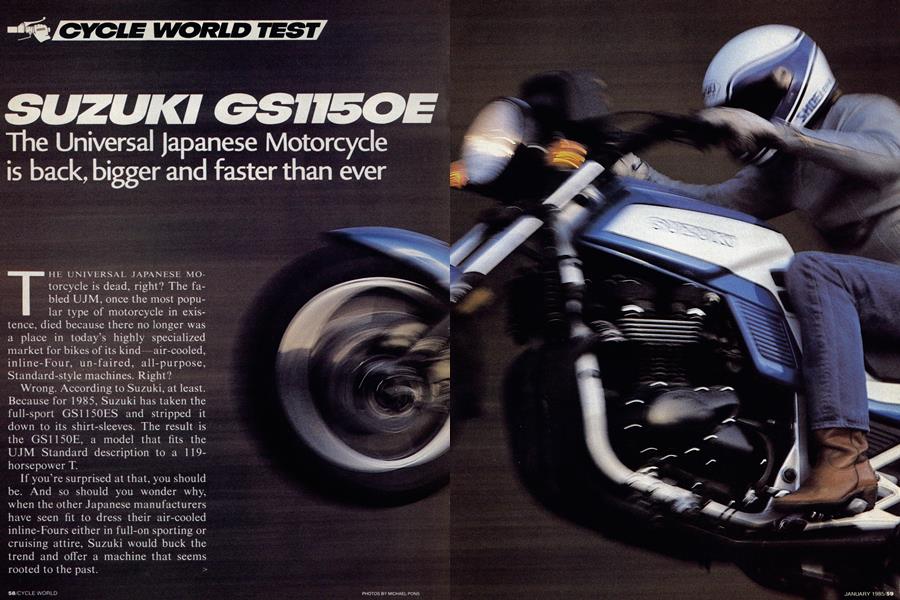

SUZUKI GS1150E

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Universal Japanese Motorcycle is back, bigger and faster than ever

THE UNIVERSAL JAPANESE MOtorcycle is dead, right? The fabled UJM, once the most popular type of motorcycle in existence, died because there no longer was a place in today's highly specialized market for bikes of its kind-air-cooled, inline-Four, un-faired, all-purpose, Standard-style machines. Right?

Wrong. According to Suzuki, at least. Because for 19S5, Suzuki has taken the full-sport GS1I5OES and stripped it down to its shirt-sleeves. The result is the GS1 150E, a model that fits the UJM Standard description to a 119horsepower T.

If you~re surprised at that, you should he. And so should you wonder why, when the other Japanese manufacturers have seen fit to dress their air-cooled inline-Fours either in full-on sporting or cruising attire, Suzuki would buck the trend and offer a machine that seems rooted to the past.

Well, there just might be a method to Suzuki’s madness. Today there are precious few alternatives for those riders who simply want a plain, unspecialized motorcycle, not a laid-back boulevard bomber or an escapee from a roadrace track. Since the only other big-bore bikes that even come close to fitting that plain-Jane requirement are Honda’s V65 Sabre and BMW’s K100, the GSI 150E is almost in a class by itself. And at $4399, the 1150E is $400 cheaper than the 1150ES, yet it retains at least the same level of engine performance that made last year’s ES-model one of the two quickest motorcycles ever sold. So based on those factors, the idea of building a UJM for 1985’s marketplace makes perfect good sense.

Actually, all Suzuki did to come up with the E-model 11 50 was to remove the ES’s sporty fairing and fit handlebars that are higher and wider than the ES’s mock clip-ons. But the end results are just short of phenomenal. Last year’s GSI 150ES was stable and steered precisely on fast mountain roads but required a lot of muscle to make snap directional changes. The bike lacked the tight-corner prowess of its sporting competition because it felt long and weighty, and it steered heavily despite its fairly quick frontend geometry and 16-inch front wheel. The E-model, however, feels much more nimble and can make those same quick maneuvers with about half the effort, yet it still shines just as brightly on super-fast, sweeping turns. Overall, in fact, the plain-Jane, unspecialized 1150E generally acts out the sportbike role slightly better than the sportintensive ES.

There are two reasons for that. One is the 12-pound weight reduction most of it at the front wheel brought on by the removal of the fairing. At 561 pounds with a full tank of gas, the E-model is the lightest speedster in its class, undercutting Yamaha’s FJ 1100 by 12 pounds and sneaking in under Kawasaki’s 900 Ninja by 4 pounds. The second reason is the E-model’s composite handlebars (cast-aluminum uprights, steel bar-ends), which are 3 inches wider and over 4 inches taller than the ES bars. So when you combine the added steering leverage of the handlebars with the reduction of weight on the front wheel, it’s not surprising that the E-model is easier to control at all speeds. Under some circumstances, the 1150 still feels like the big, long (61inch wheelbase) bike that it is, but the rider no longer is overwhelmed by the machine’s mass. Around town, in fact, the GS-E exhibits an agility that belies its heft and allows it to be one of the most manageable big-bores you can buy.

In addition, the E-model’s more-upright seating position puts less of the rider’s upper-body weight on his forearms and distributes it more evenly throughout his hindquarters; that takes some of the strain out of hard braking and makes the E more comfortable in a greater variety of riding conditions than its sporting and cruising contemporaries. Coupled with the excellent seat, which is by far the most plush saddle this side of a full-dresser’s bum-bucket, the new ergonomics have made the GSI 150E one of the most comfortable motorcycles on the market at speeds up to the legal limit. If the rider goes much faster than that, however, he’s forced to contend with the air blast that was so effectively deflected by the ES’s sporty fairing. An hour or so in the E’s saddle at speeds in excess of 60 mph can test a rider’s stamina, but no more than other unfaired motorcycles that prop their riders fully upright.

Unfortunately, an 1150E rider must also deal with fatiguing vibration. At 60 mph in top gear, the handlebars, seat, tank and rubber-mounted footpegs all become positively electric with vibration. The insistent buzzing comes and goes until the speedo hits 85 mph, whereupon the engine smooths out a bit. During the heat of battle on a fast backroad, the vibration isn’t as noticeable. But a GS rider who wants to avoid regular confrontations with the law will have to live with the buzzing generated at lesser speeds.

Nevertheless, the E-model still is less tiring to ride than the ES during those long, hard, backroad attacks, due to the same differences that make the bike more pleasant around town. While the E still requires a heavy squeeze on the clutch and brake levers, its comfortable seating arrangement and low-effort steering allow it to be flicked into fast turns and snapped through tight transitions quickly and decisively without wearing the rider out prematurely. Pure sporting bikes, like the Ninja and FJ 1100, offer superior handling precision and are easier to ride at the outer limits, but the GSI 150E has a combination of competence and comfort neither can match.

The GS-E also displays an extra measure of surefootedness not found on last year’s ES. For ’85, both the ES and E have been fitted with a '/2-inch-wider rear wheel, a */4-inchwider front wheel and stickier tires at both ends. The Emodel therefore can be pushed harder before the limits of adhesion are reached, but those limits still impose themselves sooner than on most of the bike’s sporting peers. Grab a fistful of throttle when exiting a slow corner and the GS-E’s rear wheel will spin and slue sideways. Neither tire sticks exceptionally well at maximum cornering speeds or during hard braking, but both ends do adhere to the road far better than they did last year.

On twisting roads, the E is further limited to performing a notch below the best sportbikes by its cornering clearance. During white-knuckle pursuits, or when riding at a more reasonable pace with a passenger, the E’s exhaust pipes, centerstand and solidly mounted sidestand bracket can bash into the asphalt and upset the chassis. But when there is daylight between the undercarriage and the bitumen, the E exhibits good roadholding qualities. Over sharp bumps, the rear suspension sometimes feels taut and the front end a bit harsh, but over small to medium size bumps and out on the open highway, both ends provide a firm yet comfortable ride.

The Full Floater rear suspension allows a wide range of adjustment through its remote adjusters for spring preload and rebound damping. At its softest settings, the rear suspension is too limp to accomodate spirited riding, either solo or two-up, but it provides a plush highway ride. A rider out for a quick solo dash, or one packing a passenger and weekend luggage, will find that the rear suspension can be set to handle the chore. We found, however, that the rear shock could use a bit more damping to better control the rapid spring rebound when set at maximum preload.

Up front, the 37mm fork incorporates the same PDF (Positive Damping Force) anti-dive units, four-way springpreload adjustment and interconnected air-assist system as used on the ES. The PDF system provides both positionsensitive and velocity-sensitive compression damping and is activated independently from the front brake system. This has rid the 11 50 of the spongy front brakes that were prevalent with Suzuki's pre-1984 anti-dives, but the PDF system has its own problems. A spring-loaded valve restricts internal oil passageways when there is a sudden rise in fork oil pressure following hard braking or road irregularities. Consequently, this system can’t distinguish between fork dive caused by braking or fork compression caused by bumps in the road, and it is possible to activate the PDF’s heavy compression damping when riding hard through a bumpy corner. This can cause the fork to stiffen unexpectedly, lose its responsiveness and chatter off the rider’s chosen cornering line.

Though the PDF unit can be adjusted to any one of four positions, each of which alters the point in the fork travel at which the system is activated, none of the settings completely alleviates the problem. Fortunately, the absence of the ES’s fairing makes the E less prone to excessive frontend dive during hard braking, thereby allowing the PDF unit to be set in the No. I position. This prevents the system from being activated until the fork has compressed 5.4 inches; and, that, along with the recommended 4.3 psi of air in the fork, offers the best response in most riding conditions.

Despite any improvements the PDF system might have caused in front-brake feel, however, the brake still lacks linear feel and precise feedback, even though it never fades and always provides good stopping power. It also demands high lever-effort that isn’t a drawback during workaday travels and moderately paced backroad adventures, but that can wreak havoc with your arm muscles after 30 minutes or so of frequent hard use. The rear brake also provides good stopping power, but likewise requires a lot of pressure for maximum efficiency and returns little useful feedback when used aggressively on a twisty road.

The engine won’t ever leave you feeling shortchanged, however, no matter where you’re riding. Though it’s the same as it was in last year’s (and this year’s, as well) l 150ES, the 16-valve, air-cooled, inline-Four is still a powerhouse of the highest magnitude. From around 3000 rpm ail the way up to its nine-grand redline, the big doublecammer produces a staggering amount of torque. There are never any sudden jumps in power, just a smooth, relentless, brutally strong rush of horsepower that seems intent on yanking the bike right out from under you. It also allows you to use any one of several gears to zap past highway traffic or launch out of corners in a real eye-opening rush. Ignore the tachometer, forget about the gearbox and just let the GS’s broad muscle hustle you down the road. Few motorcycles can boast the kind of power that the GSl 150 puts out, and fewer still spread that power over as broad of an rpm range.

Powerful and entertaining as the GS-E's engine is, it is not without its annoyances. There’s the aforementioned vibration, and the EPA-pleasing lean carburetion that causes the GS to surge slightly at partial throttle openings, most noticeably at around 60 mph. This lean jetting also makes the GS cold-blooded enough to require an extended warmup period on chilly mornings. But on the positive side, if the rider resists the strong temptation to whack the throttle open every chance he gets, the E-model will repay him with respectable fuel mileage, and run longer between fill-ups than most people care to ride in one uninterrupted stint.

This sort of practicality is indicative of the GSl l50E’s overall character. With its air-cooled, transverse-Four engine and long-wheelbase chassis, the bike is a clear step behind the cutting edge of motorcycle technology; but in real-world terms, the GSl l 50E offers the sort of flexibility that most other motorcycles can’t provide. It is highly versatile, comfortable, competent, astonishingly powerful, easy to ride and, perhaps most importantly, more affordable than any of its competition. At a time when motorcycles are becoming increasingly more specialized and correspondingly more expensive, the GS1150E makes good sense.

So don’t think of it as a throwback to yesterday’s UJM; think of it as the fastest, most powerful Standard ever built. And probably the best performance-per-dollar bargain of 1985.

SUZUKI

GS1150E

$4399

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

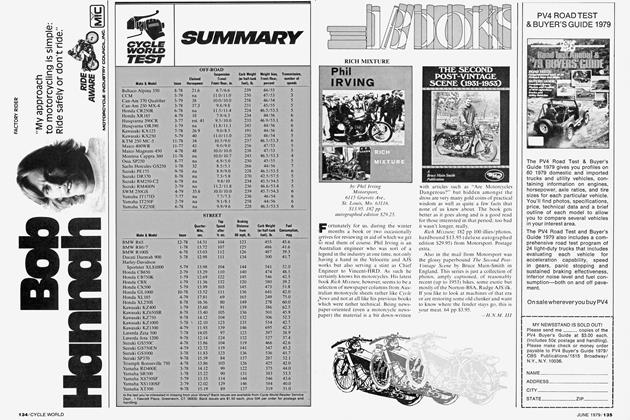

View Full Issue

View Full Issue