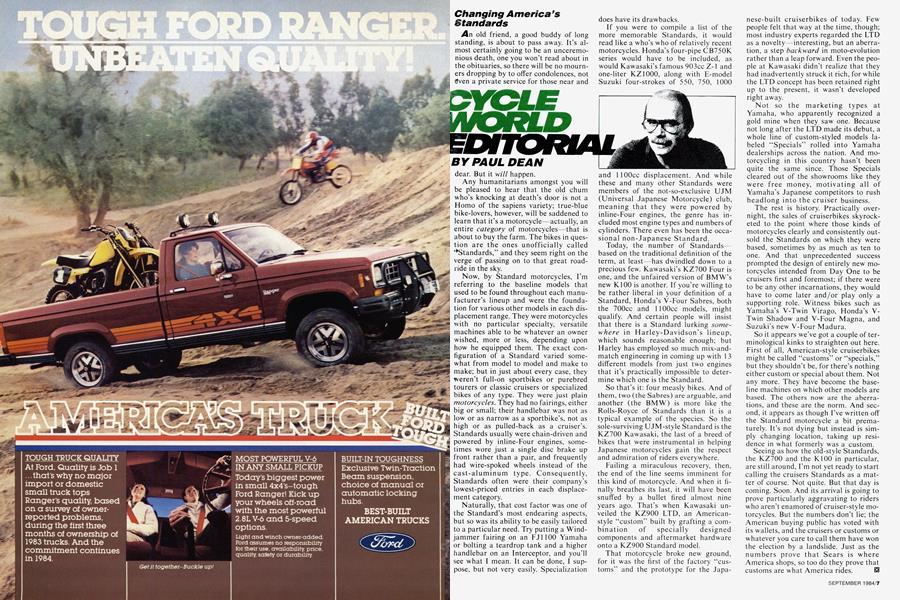

CYCLE WORLD EDITORIAL

Changing America's Standards

PAUL DEAN

An old friend, a good buddy of long standing, is about to pass away. It's almost certainly going to be an unceremonious death, one you won't read about in the obituaries, so there will be no mourners dropping by to offer condolences, not even a private service for those near and dear. But it will happen.

Any humanitarians amongst you will be pleased to hear that the old chum who’s knocking at death’s door is not a Homo of the sapiens variety; true-blue bike-lovers, however, will be saddened to learn that it’s a motorcycle—actually, an entire category of motorcycles—that is about to buy the farm. The bikes in question are the ones unofficially called ‘^Standards,” and they seem right on the verge of passing on to that great roadride in the sky.

Now, by Standard motorcycles, I’m referring to the baseline models that used to be found throughout each manufacturer’s lineup and were the foundation for various other models in each displacement range. They were motorcycles with no particular specialty, versatile machines able to be whatever an owner wished, more or less, depending upon how he equipped them. The exact configuration of a Standard varied somewhat from model to model and make to make; but in just about every case, they weren’t full-on sportbikes or purebred tourers or classic cruisers or specialized bikes of any type. They were just plain motorcycles. They had no fairings, either big or small; their handlebar was not as low or as narrow as a sportbike’s, not as high or as pulled-back as a cruiser’s. Standards usually were chain-driven and powered by inline-Four engines, sometimes wore just a single disc brake up front rather than a pair, and frequently had wire-spoked wheels instead of the cast-aluminum type. Consequently, Standards often were their company’s lowest-priced entries in each displacement category.

Naturally, that cost factor was one of the Standard’s most endearing aspects, but so was its ability to be easily tailored to a particular need. Try putting a Windjammer fairing on an FJ1100 Yamaha or bolting a teardrop tank and a higher handlebar on an Interceptor, and you’ll see what I mean. It can be done, I suppose, but not very easily. Specialization does have its drawbacks.

If you were to compile a list of the more memorable Standards, it would read like a who’s who of relatively recent motorcycles. Honda’s four-pipe CB750K series would have to be included, as would Kawasaki’s famous 903cc Z-l and one-liter KZ1000, along with E-model Suzuki four-strokes of 550, 750, 1000 and llOOcc displacement. And while these and many other Standards were members of the not-so-exclusive UJM (Universal Japanese Motorcycle) club, meaning that they were powered by inline-Four engines, the genre has included most engine types and numbers of cylinders. There even has been the occasional non-Japanese Standard.

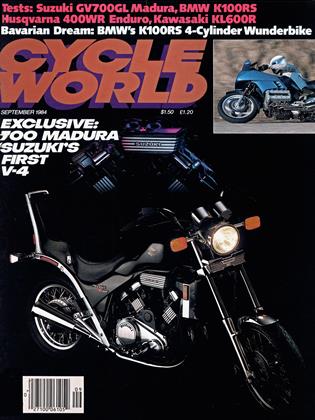

Today, the number of Standards based on the traditional definition of the term, at least—has dwindled down to a precious few. Kawasaki’s KZ700 Four is one, and the unfaired version of BMW’s new K100 is another. If you’re willing to be rather liberal in your definition of a Standard, Honda’s V-Four Sabres, both the 700cc and llOOcc models, might qualify. And certain people will insist that there is a Standard lurking somewhere in Harley-Davidson’s lineup, which sounds reasonable enough; but Harley has employed so much mix-andmatch engineering in coming up with 13 different models from just two engines that it’s practically impossible to determine which one is the Standard.

So that’s it: four measly bikes. And of them, two (the Sabres) are arguable, and another (the BMW) is more like the Rolls-Royce of Standards than it is a typical example of the species. So the sole-surviving UJM-style Standard is the KZ700 Kawasaki, the last of a breed of bikes that were instrumental in helping Japanese motorcycles gain the respect and admiration of riders everywhere.

Failing a miraculous recovery, then, the end of the line seems imminent for this kind of motorcycle. And when it finally breathes its last, it will have been snuffed by a bullet fired almost nine years ago. That’s when Kawasaki unveiled the KZ900 FTD, an Americanstyle “custom” built by grafting a combination of specially designed components and aftermarket hardware onto a KZ900 Standard model.

That motorcycle broke new ground, for it was the first of the factory “customs” and the prototype for the Japanese-built cruiserbikes of today. Few people felt that way at the time, though; most industry experts regarded the FTD as a novelty—interesting, but an aberration, a step backward in moto-evolution rather than a leap forward. Even the people at Kawasaki didn’t realize that they had inadvertently struck it rich, for while the FTD concept has been retained right up to the present, it wasn’t developed right away.

Not so the marketing types at Yamaha, who apparently recognized a gold mine when they saw one. Because not long after the FTD made its debut, a whole line of custom-styled models labeled “Specials” rolled into Yamaha dealerships across the nation. And motorcycling in this country hasn’t been quite the same since. Those Specials cleared out of the showrooms like they were free money, motivating all of Yamaha’s Japanese competitors to rush headlong into the cruiser business.

The rest is history. Practically overnight, the sales of cruiserbikes skyrocketed to the point where those kinds of motorcycles clearly and consistently outsold the Standards on which they were based, sometimes by as much as ten to one. And that unprecedented success prompted the design of entirely new motorcycles intended from Day One to be cruisers first and foremost; if there were to be any other incarnations, they would have to come later and/or play only a supporting role. Witness bikes such as Yamaha’s V-Twin Virago, Honda’s VTwin Shadow and V-Four Magna, and Suzuki’s new V-Four Madura.

So it appears we’ve got a couple of terminological kinks to straighten out here. First of all, American-style cruiserbikes might be called “customs” or “specials,” but they shouldn’t be, for there’s nothing either custom or special about them. Not any more. They have become the baseline machines on which other models are based. The others now are the aberrations, and these are the norm. And second, it appears as though I’ve written off the Standard motorcycle a bit prematurely. It’s not dying but instead is simply changing location, taking up residence in what formerly was a custom.

Seeing as how the old-style Standards, the KZ700 and the K100 in particular, are still around, I’m not yet ready to start calling the cruisers Standards as a matter of course. Not quite. But that day is coming. Soon. And its arrival is going to prove particularly aggravating to riders who aren’t enamored of cruiser-style motorcycles. But the numbers don’t lie; the American buying public has voted with its wallets, and the cruisers or customs or whatever you care to call them have won the election by a landslide. Just as the numbers prove that Sears is where America shops, so too do they prove that customs are what America rides. El

View Full Issue

View Full Issue