THE TERRIBLE TWIN REVISTED

HOW SUZUKI'S X6 HUSTLER SHOCKED THE WORLD IN 1966, AND WHAT IT'S LIKE TODAY.

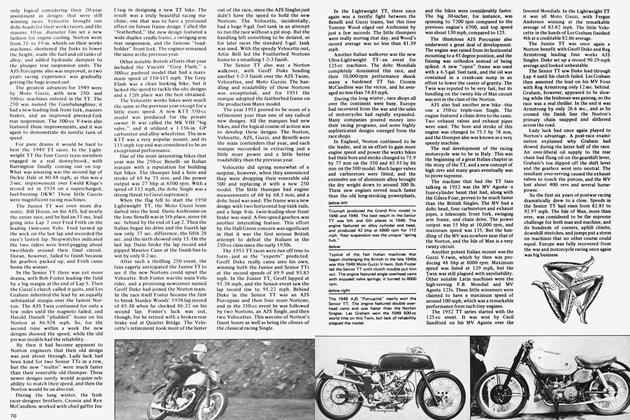

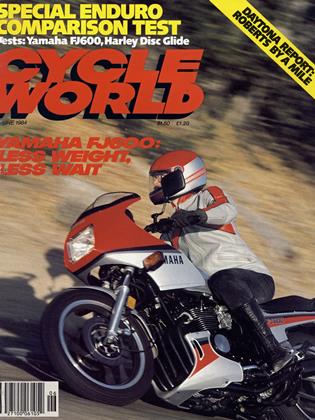

From the perspective of 1984 the X6 Suzuki is a toy. Borrowed for purposes of nostalgia, the X6 was housed in our garage . . . and disappeared, dwarfed by the Honda V65 and Kawasaki Ninja, overshadowed by the Yamaha FJ600 and Harley FXRDG, towered over by 250cc enduros. Gosh, said those discerning few who spotted the tiny terror, somebody’s bought another old bike. Looks like a 100 Twin.

And so it does. Today. Hard though it is to imagine,in this era of horsepower listed, in three figures and machines that tip the scales at 500 lb. but aren’t quite heavyweights, the X6 Hustler looks like something made for a 12-year-old.

How things have changed. In 1966, when the X6 first hit the showrooms, it was the fastest production 250 made. It wasn't a nice little bike, it was a great bike, a bike with a reputation, the bike that won Suzuki a reputation as a maker of high-performance machinery.

How and why need a review of what it was like back in 1966. There were high-performance machines, of course. They came from Triumph, Norton, BSA and Harley. They were > big Twins, loud and demanding, big (for their time) and powerful (relatively speaking) and few of their riders even knew there were such things as Japanese motorcycles, never mind considering the purchase of one.

At the other end were the kids who knew the Japanese made bikes. They owned them, and liked them, but when kids on Honda 50s and 90s went to the Suzuki store to look at the X6, they were shown something a little less ambitious. For them there were 120cc Singles and a tepid little 150cc Twin. The X6 was a full 250 Twin, just too much motorcycle for someone who’d only been riding for a couple of years. It was a terror.

Suzuki planned it that way. They were new to the U.S. market, so new that their arrival was trumpeted “Suzuki Are Here!” Their officials spoke English but didn’t know English isn't American, that in the U.K. a company takes the plural while in the U.S. a company is singular. They used silly model names. (Hustler may have been overdone, but it wasn’t on a par with the Hill-Billy). And they made nice little bikes.

Quick learners, though. Thanks to road racing and some acquired technology, they knew a lot about two-strokes. And they guessed (rightly) that Americans liked performance. So they went to the far edge, with aluminum cylinders, something so rare at that time that our test solemnly explained the advantages, and six speeds and a state of tune that delivered 29 bhp at 7500 rpm. And it was a 250, a perfect, not to say magic, number.

The big (again, relatively) Japanese motorcycles of the mid-Sixties weren't 250s and 305s because these were the best size for a motorcycle. The Japanese bikes grew out of basic transportation, from 50s and 90s, and the taxing and licensing structures of some countries, especially Japan, made some sizes natural stops along the way.

Two-fifties ended up being one of those wonderfully right sizes. A 250>

could carry two people without much difficulty, while anything smaller always felt as if the front tire were 2 in. off the ground. A good 250, like the X6, could be made to go 100 mph. This is a magic speed. Any motorcycle that can go 100 mph is genuinely fast. A bike that can’t hit 100 isn’t really fast. If a 250 were built well enough, it could be ridden anywhere.

Sure, people have ridden around the world on mopeds. But below 250cc there's a degree of challenge to the ride that makes it a special event. On a good 250 you're just on a motorcycle ride, no matter how long.

At least on a reliable 250 a long ride was no problem. There were lots of 250cc motorcycles available in the mid-Sixties that didn’t have the stamina for crossstate rides. They weren't high-stressed, powerful little bikes. They were most often the slowest 250s. The bike designed to put out 1 5 horsepower and run 70 mph not only couldn't handle any more power, it often couldn’t stand up to the power it had. Slow motorcycles were often just bad motorcycles.

The X6 wasn’t like that. Remember that the Japanese bike companies built up, from the smallest displacement classes, where high specific output was normal. So the X6 didn't have any trouble holding together while the rider used 29 bhp. It was designed for the job. This wasn’t an enlarged 150 or 200cc motorcycle, it was a 250, and when it grew to a 305 and then to a 31 5cc 350, it still managed to hold together.

Two-stroke motorcycles didn’t have the sort of reliability reputation you’d pay money for, at least not when the X6 first appeared. The Hustler, as much as any motorcycle, can take credit for changing that.

If there was any one aspect of the Suzuki’s design that made for great reliability, it was the lubrication system. Note that this is a system. It’s not so much oil poured in the gas tank. Several

manufacturers were installing oil tanks on two-strokes, with various meters dribbling the oil into the intake, but only the Suzuki had a variable-displacement pump controlled by throttle position and injecting oil directly to the crankshaft and the cylinder walls.

This virtually eliminated seizure, and it also reduced oil consumption and the typical two-stroke smoky exhaust. Not having to carry around a can of twostroke oil for iill-ups was more convenient, too. A quart of oil could fill the oil sump on the right side of the bike, and it could last up to 1000 mi. if you rode gently. Few riders did.

Because the X6 Suzuki, like the usefully speedy Hondas and Yamahas of the day, was durable and didn't require much effort to keep working, it didn’t get much maintenance. People who bought Suzukis and Hondas and Yamahas bought them to ride. These weren’t models, they were motorcycles. That has made it hard to find nicely kept examples

of the 250 Suzuki Twins.

As an example of the X6 Suzuki, Craig Vetter’s bike is a good one. As the photos show, the paint is faded, the front fender is slightly dented and the side covers sport a few scratches. This is what X6 Suzukis looked like after a couple of years of use.

(Anyone looking for a good X6 might want to contact Craig at (805) 541-3330. He’s got this one for sale.)

All old bikes bring back memories or sensations from their own time. In the case of the Suzuki, that time wasn’t so long ago. Tens of thousands, maybe even a couple of million riders can remember riding bikes like this Suzuki.

Eighteen years ago the X6 felt considerably different, only because the other bikes around were so much different. Then, the X6 was a fabulously fast, intimidating motorcycle. The advertisements said the Suzuki could turn a 14.8sec. quarter-mile. Only a few motorcycles were quicker, and they were all more than twice as large as the Suzuki. This was a motorcycle to be reckoned with.

To give the Suzuki the look of a big bike, the 250 has a full double-cradle steel tube frame. As normal as that seems now, it was not so common for the Japanese bikes of the Sixties. Then, a pressed steel backbone was most often used, sometimes with a brace linking the engine to the structure. The backbone frame probably had more strength per pound and per dollar than a steel tube frame, but big bikes had tube frames, so the X6 had one.

Motorcycle styling, which now means a bike looks like a Harley or a roadracer, was with us in 1966. On the Suzuki it means the gas tank has chrome sides and the shape of the tank bulges out at the rear. An 8000-rpm tachometer and 120mph speedometer are integrated with the headlight shell, and the needles for those instruments swing in semi-circles to their right. A similar treatment can be found on Suzuki’s Katana. And the gas tank bigger in back than in front is reappearing on several current big Japanese bikes.

Styling didn't mean as much 18 years ago. There were high-pipe styles and low-pipe styles, and the Suzuki had exposed fork springs, which looked racy, but whatever efforts had gone into the style of the Suzuki seemed secondary to the engineering efforts. Nothing in the Suzuki’s style interfered with riding the bike.

That isn’t to say all was standard. Back in 1966 standard meant what the factory thought the customer expected, rather than what the various government bureaus had dictated.

Thus, the X6 had a leftside shift, one down and five up. It also had a shift shaft that ran all the way across the cases so the shift could be on the right in other markets. The ignition switch was in the headlight shell, a familiar location in those days and the fuel petcock is marked 2-1-0; presumably the O means off, the 1 is the primary and 2 is the secondary supply, a.k.a reserve.

Riding the X6 is the best way to understand how far motorcycles have come. To say the X6 weighs half as much as the Honda V65 Sabre doesn’t convey the difference of magnitude. Getting the X6 off its sidestand takes maybe a 15lb. pull. The Honda comes off the stand with about 80 lb., from both hands. From the saddle the rider isn’t aware of getting the Suzuki off the sidestand and in balance. The Honda takes a mighty heave, a well-planted foot and a long leg.

The X6 is a little motorcycle. It has a moderately low seat, but with no towering tailpiece to climb over. You sit on the Suzuki in much the same posture you'd sit on a Honda 50. Starting the Suzuki Twin is something so easy to do no one would think of equipping the bike with an electric starter. You don’t kick the Suzuki starter, you push it with your foot and the little Twin excitedly leaps to life.

Riding the Suzuki is just as easy as starting it. Pull in the clutch, snick it into gear and let the clutch out as you roll on the throttle. This isn't one of those bikes you have to rev up to move away. Normal riding means 2000 rpm when you let the clutch out. The engine revs easily up to whatever rpm you want. There’s a surge around 6000 rpm, but it’s nothing to be scared of. It’s just a little surge in acceleration. This is a mild-mannered motorcycle.

And that's the surprise. The X6 Suzuki isn’t a terror. You don’t have to hide the women and children. They’d probably find the X6 a nice bike to ride.

As simple as motorcycles are, mechanically, the sensations they give a rider are complex. The ease with which all the controls work on the X6 are a match for any current commuter bike. That makes the bike feel easy to ride. Like most any light, small motorcycle, the Suzuki steers with minimal force on the handlebars. That makes it feel sporting and agile. Because it has six speeds think of that, six speeds fit lends itself to rowing through the gears and keeping the smooth-running engine wound up. That makes it feel fast.

Sound and vibration cause other sensations. The Suzuki is a smooth-running two-stroke Twin, but there is moderate high-frequency vibration when the rpm is high. The sound is muted and low, very different from most two-strokes of the period. That subdued exhaust does much to give the X6 its civilized air.

So. What the rider is left with after a ride on the X6 is a feeling that this is a nice, fun little motorcycle. We were obviously naive when the X6 stunned us with its power in 1966. We had no 120 horsepower bikes for comparison. We had 20 and 30 bhp bikes. Some of us had 5 bhp bikes.

The X6 Suzuki was a stepping stone for those who built motorcycles and for those of us who rode them. Stepping on those stones today, the trail is hard to recognize.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

June 1984 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

June 1984 -

Daytona '84

Daytona '84Welcome To Daytona

June 1984 By David Edwards -

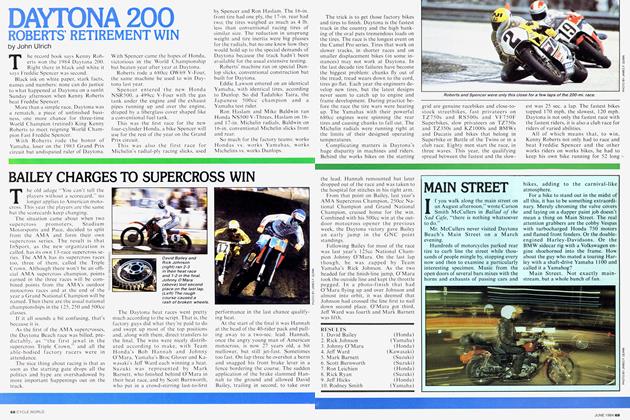

Daytona '84

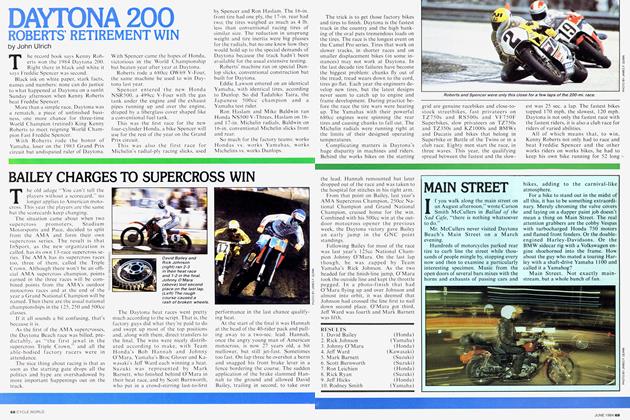

Daytona '84Daytona 200 Roberts' Retirement Win

June 1984 By John Ulrich -

Daytona '84

Daytona '84Bailey Charges To Supercross Win

June 1984 -

Daytona '84

Daytona '84Main Street

June 1984