HONDA XR350R

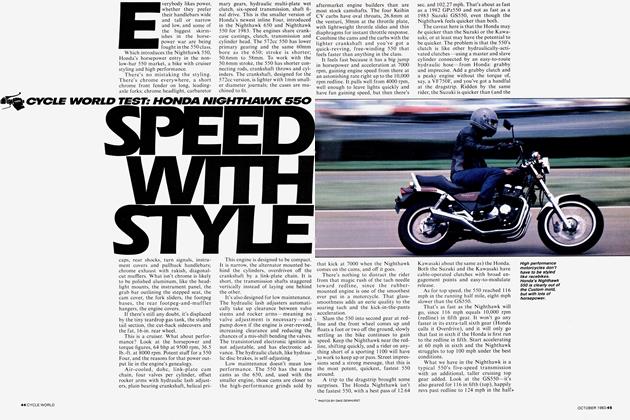

CYCLE WORLD TEST

By now the Honda technique for creating new models ought to be in textbooks. Instead of copying existing models, Honda has made a habit (and a fortune) of building models unlike what

everybody else has. When every other manufacturer built only two-stroke motorcycles for off-road use, Honda came out with, first, the XL series of four-stroke dual purpose bikes and then the XR series of four-stroke enduro bikes.

Honda has also been successful following design leads. When Yamaha’s TT500 became successful, Honda followed with the even more successful XR500. It was a good bike carefully developed and now Honda’s line of fourstroke enduro bikes has led to another generation, once again containing enormous improvements.

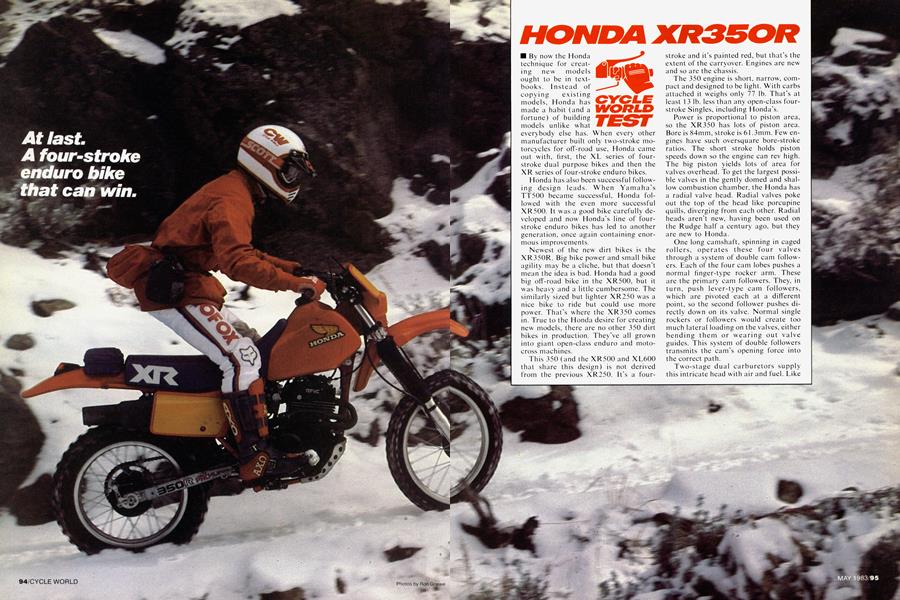

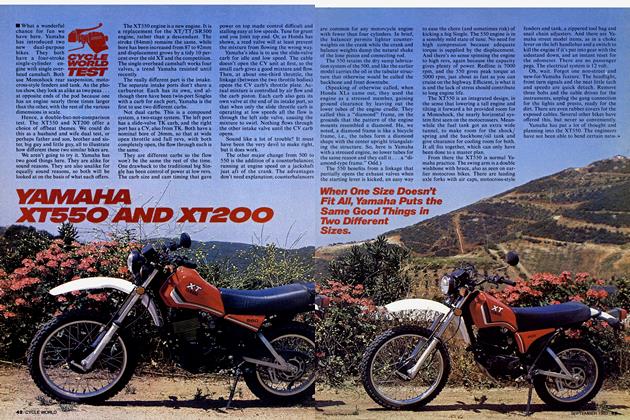

Newest of the new dirt bikes is the XR350R. Big bike power and small bike agility may be a cliche, but that doesn’t mean the idea is bad. Honda had a good big off-road bike in the XR500, but it was heavy and a little cumbersome. The similarly sized but lighter XR250 was a nice bike to ride but could use more power. That’s where the XR350 comes in. True to the Honda desire for creating new models, there are no other 350 dirt bikes in production. They’ve all grown into giant open-class enduro and motocross machines.

This 350 (and the XR500 and XL600 that share this design) is not derived from the previous XR250. It's a four-

stroke and it’s painted red, but that’s the extent of the carryover. Engines are new and so are the chassis.

The 350 engine is short, narrow, compact and designed to be light. With carbs attached it weighs only 77 lb. That’s at least 1 3 lb. less than any open-class fourstroke Singles, including Honda’s.

Power is proportional to piston area, so the XR350 has lots of piston area. Bore is 84mm, stroke is 61,3mm. Few engines have such oversquare bore-stroke ratios. The short stroke holds piston speeds down so the engine can rev high. The big piston yields lots of area for valves overhead. To get the largest possible valves in the gently domed and shallow combustion chamber, the Honda has a radial valve head. Radial valves poke out the top of the head like porcupine quills, diverging from each other. Radial heads aren't new, having been used on the Rudge half a century ago, but they are new to Honda.

One long camshaft, spinning in caged rollers, operates these four valves through a system of double cam followers. Each of the four cam lobes pushes a normal finger-type rocker arm. These are the primary cam followers. They, in turn, push lever-type cam followers, which are pivoted each at a different point, so the second follower pushes directly down on its valve. Normal single rockers or followers would create too much lateral loading on the valves, either bending them or wearing out valve guides. This system of double followers transmits the cam's opening force into the correct path.

Two-stage dual carburetors supply this intricate head with air and fuel. Like

the Yamaha XT550, one carburetor throat is used at low throttle settings and the second comes into use at large throttle openings. Unlike the Yamaha, the Honda uses a mechanically linked secondary, instead of a vacuum-controlled secondary. Only the lefthand carb has a primary circuit. When the throttle is one-third open the secondary cuts in. A tiny crossover links the two separate intake ports, and a single steel reed valve allows this to open only at high pressure differential, just before the secondary opens.

Both carburetors are slide throttle, controlled by a dual-cable, push-pull throttle. Transition from primary to secondary is so smooth it isn't noticed.

Separate exhaust ports are also found on the XR, with the individual exhaust pipes merging as they wrap around the right side of the engine. An opening between the exhaust ports allows cooling air to reach the center of the head, where the spark plug is located.

An automatic cam chain adjuster pushes the long slipper tensioner onto the link-plate cam chain. On the end of the adjuster is a heat-sensitive tip that reduces tension when cold so the cam chain isn't too tight when cool.

A lightweight crankshaft with chopped, not full-circle, counterweights holds the rod with caged roller bearings. At the top of the rod the wrist pin operates without a bushing. The giant flat topped piston has four tiny quarter-cut depressions for the valves. Three rings are used, the top a compression, the second a scraper and the bottom a threepiece oil control ring.

In front of the crankshaft is the geardriven counterbalancer shaft. A split gear, with spring-loaded halves, is used. This tensions the double row of teeth, eliminating backlash and noise from the gear drive. An outside flywheel GDI magneto is mounted on the left end of the crank, and the straight-cut gear driving the clutch is on the right. Six fiber plates

and five steel plates are held together by four coil springs. Other gears under the clutch cover connect the primary kick starter and the lightweight aluminumhoused oil pump. An easily accessible paper oil filter receives all oil from the pump before it's routed through external oil lines to and from the top end of the engine. Internal steel oil lines pressurize the transmission shafts from the 2 qt. oil supply.

Caged roller bearings hold the transmission shafts and the small end of the shift drum. Each of the two transmission shafts hold six gears, engaged by a combination of round and square dogs. Elongated dog slots make gear changing easy.

Magnesium sidecovers fit on the aluminum center cases. The lightweight clutch cover even has a needle bearing for the kick shaft. Multiple layer sandwiched steel gaskets are used for the head and cam covers, eliminating any oil leakage.

Previous XR Hondas did not have state-of-the-art chassis. The frame and suspension on the XR350 is vastly improved. Show a forks with 41mm stanchions and 1 1 in. of travel are held in double bolt triple clamps. A single fourbolt clamp holds ihe axle on the right leg. Two low-friction bushings are held in the sliders, instead of the usual one. The bulge in the outside of the slider holds the bottom bushing, replacing a bushing on the end of the stanchion. This reduces friction in the first few inches of travel, according to Honda. Quality fork gaiters keep dirt out of the seals. No damping adjustments are provided, limiting fork tuning to oil weight and volume and air pressure. Recommended air pressure is zero.

Rear suspension is handled by a single shock Pro-Link system. As with the rest of the bike, much attention to detail and material selection is evident. The ProLink arms, shock body and reservoir are forged aluminum. All moving links on the levers have grease nipples. The

Showa shock features adjustable compression and rebound damping: the rebound is adjusted by turning a plastic knob just above the lower clevis. The outer edge of the plastic wheel is numbered one to four. The standard number two position worked best. The rebound damping adjuster on the parallelmounted reservoir has a red mark for the standard position. Honda recommends trying the standard position before experimenting with different ones. From 8 to 1 2 different settings are possible on the compression damper, depending on the shock and how it's assembled. The red mark shows the middle of each shock's adjustments. A click detent at each position is hard to feel with a gloved hand. We liked the compression damping when adjusted two clicks softer.

Lor the first time in the XR's history, the engine is wrapped in a full-cradle chrome-moly tube frame. And also for the first time, all of the tubes appear large enough. There’s a lot of boxed gusseting around the steep 26° steering head and the area is further strengthened by a tube between the front downtube and the large backbone tube. Good triangulation is present in the frame's midsection. Smaller, but still large, tubes are welded to the main frame members with short tubes extending back to hold the rear fender and do double duty as lift handles. Too bad the rear section doesn’t bolt on like the CR’s. It would certainly make shock access easier. The engine bolts into the frame in five places: aluminum brackets tie it to the front downtube and valve cover to top tube; long through bolts hold the upper and lower rear and lower front. Funny they didn't use the swing arm bolt to hold the rear. Engine and frame protection is first class. A nice stamped aluminum skid plate wraps the engine. It curves around each side of the engine before flaring out to divert blows. It’s also stamped full of holes to reduce weight and mud buildup, but still collects more mud than six-day bars. Even the

right front bolt for the footpeg is protected by the skidplate.

An aluminum-painted steel swing arm adds maybe 3 or 4 lb. and saves a few dollars. The chrome-moly arm has nice rectangular legs, good cross bracing and snail-type axle adjusters. An open-ended axle slot, combined with a travel limiter plate to keep the axle from sliding too far back, and a quick-detach rear brake rod make wheel removal easy. There’s not even a static arm. The backing plate plugs into a tab on the swing arm.

Small hubs are connected to aluminum rims with straight-pull spokes. Rear brake diameter is 4.3 in. and the front is 5.1 in. In addition to the serrated bead surface on the rims, a single conventional rim lock is included. A large valve stem hole makes tube changing easy and reduces the chances of a torn stem when a tire goes flat. The six-ply rated Bridgestone tires are't likely to be shredded on rocks and have the same tread pattern as Bridgestone’s great new motocross tires.

Plastic parts add greatly to the XR’s appearance. The front fender is wide and extends far forward, but only a short way down behind the tire. It somehow doesn't let much water splash on the rider, though, nor does the rear fender. A tall, stubby, 3.2 gal. plastic gas tank isn't excessively wide and has a big filler opening. The petcock includes reserve. Side number plates are farther forward than on a motocrosser because enduro riders depend more on the front number plate for identification. The right number plate is easily removed by loosening one screw and unplugging. On the left, the number plate forms the side of the airbox and it's held on with three screws. This takes more effort for air filter servicing, but it forms a good watertight seal. The intake is on the top of the airbox, where it's well protected from water. A double layer filter is held in the wide airbox by a wire bracket. From the airbox, intake tubes wrap around both sides of the

shock to feed the two carburetor bores.

Stock lighting includes a 35-watt rectangular bulb in front and a 3-watt bulb in back. An optional 55-watt halogen light is easily powered by the 58-watt electrical system and allows riders to have fun in the dark. The stock light produces a yellowish color and is adequate up to 30 or 40 mph at night. Four rubber straps hold the quick detach headlightnumberplate and the beam is easily cranked up and down with a simple adjuster screw.

The blue safety seat will make longdistanceriders grin. Like its motocross brother, it’s shaped right, has well rounded edges, firm foam with a springy top, and an excellent cover that could easily pass for leather. The plastic base slides into a bracket at the front and is held in back by two 6mm screws under the rear fender.

All of the necessary enduro accessories come as standard equipment. There’s a rear-fender mounted tool bag, made of the same material as the seat. The bag comes with a plug wrench, multi-purpose wrench and screw drivers. The tools are held in a pouch in the front part of the bag so they don’t bounce around and self destruet. The shift and rear brake pedal are made of steel for strength. Both have folding tips so rocks and tree roots don’t bend them. Hand levers are the norm for late model XRs. They have dogleg shapes with the ballend of the levers pulled back so they don't catch on brushes and trees. The throttle is a small, neat two cable push/pull affair. It works smoothly and opens the carbs with a quarter turn. A combination odo and speedometer is provided. The odo has a small knob for minor adjustments, a larger knob for major changes. The numerals on the odo are magnified by the lens and they are easy to see while you’re being bounced around. The large silencer has a spark arrester so it’s legal in the woods. A side stand is stock but there’s no provision for

a center stand.

Just sitting on the XR350 is fun. Simply put, it feels right. Static seat height is 36.8 in. but the progressive rear suspension settles with the rider’s weight and most of our guys could easily touch the ground without tippy-toes. Bars, pegs and levers are positioned right and in general, the XR350 feels small and light.

Starting hot or cold is no hassle. There’s an automatic compression release linked to the kick start. Llick on the choke if the engine’s cold, forget the choke if it’s warm, and kick through all the way. Full use of the lever’s travel is important on four-stroke Singles because unlike two-strokes they don’t start well when the lever is just jabbed. A fourstroke has lots of parts to spin and needs the complete follow through to spin them all fast enough. Don't crack the throttle, either. Jabbing the lever or opening the throttle both are sure ways to add more kicks to the drill.

When the XR350 fires, it's safe to use a bit of throttle and it's necessary to leave the choke on until the engine warms up. The 350 is cold blooded.

Throttle response is very quick for a four-stroke Single. There is a small hesitation right at the bottom, coming off idle, a common problem with this type of engine but worse on this bike due to jetting on the primary carburetor. Clutch pull is light but the rear-set lever ballend feels like a broken lever. The transmission clicks into gear easily and without any lurching. Easing the clutch lever out moves the bike away smoothly without the normal four-stroke Single leap. The lever shifts into second with a slight nudge of the rider's left toe. Smooth and positive. Shifting up through the rest of the six-speed gearbox brings a smile to the rider’s face; this is the easiest shifting XR ever. All the rider has to do is slightly move the lever and it'll snick into the next gear.

Engine power is plentiful and deceptively strong. Like any four-stroke, (the

full-out track racing engines aside), the engine doesn’t make the rider as aware of the power as a two-stroke that fires every revolution. After a couple of miles the rider starts getting the message. The XR350 will climb really steep hills in second. And the front end has a light feel never before experienced on an XR. Lofting the front wheel over obstacles at trail speeds is as simple as blipping the throttle. At higher speeds the front wheel is easily lifted by turning the throttle to the stop and giving the bars a little tug. Balance is good with the front wheel in the air; it stays up until the rider wants it down or the bike’s speed increases to the point the front drops on its own. The rider also becomes aware that something else about this four-stroke Single is different than normal. There’s no vibration and no boom, boom as the piston fires, even at low speeds. Blipping the throttle with the transmission in neutral the rider can feel a slight rolling bump, as if it was deadened by water. And there’s none of the normal four-stroke Single’s internal clatter and rattle. No cam chain noise, no balancer drive noise, no valve or rocker arm noise.

The first tight trail through the woods demonstrates what Honda designed the XR350 for. Its short wheelbase and 26° rake let the rider carve his way through dense woods with a precision many have never experienced. In fact, the XR350 is so quick to change directions and so sensitive to slight rider input it takes most riders an hour or so to adapt. Forget about sliding up to the front of the seat, it’s not necessary unless there is a sudden hairpin turn. Just sit wherever you’re comfortable and steer the bike.

With steering this quick we were cautious in the first sandwash. No problem, the XR is a little quicker in sand than most but it isn't a bit spooky and the front end never shakes. Same for braking hard into whooped corners: no

headshake or foul manners. Our concern about the small brakes proved un-

founded. They are plenty strong. The first trip out, the back brake nearly drove us nuts by constantly squealing. It was terrible. Back at the shop we sanded the glazed lining. End of squeal.

The engine’s low-speed stumble was a nuisance and we decided to try and rejet the primary carburetor. Dropping the needle on the carb should help clean up the roughness and stumble. Two and a half hours later it was done. We could have overhauled the top end of a twostroke Single in less time. Dropping the needle required the removal of the gas tank, seat, side panels, and throttle cables from the carb linkage. Additionally, the top shock bolt had to be removed, the shock pushed rearward and the airbox unbolted and pushed back, and the intake unbolted and slid up out of the way. Then it was possible to remove the carbs. Both have to come off the bike as a unit. Even with all these parts moved around the carbs were hard to get out of the space between the engine and frame. It would have been easier to also remove the shock reservoir! Once the carbs are on the work bench one has to figure out how to get the linkage unhooked and the slide out, no simple job on side-pull carbs. After the needle clip was raised one notch, dropping the needle to a leaner position, all of the bits and pieces had to be reassembled. Part of the time spent was figuring out what to do. The job could probably be repeated in half the time or less. Even so, compared to the couple minutes needed for the same job on a two-stroke Single, it’s a hell of a job.

Back on the trail the XR ran better. Much of the stumble disappeared but the pilot jet didn’t seem quite right. There was still a slight hesitation off idle. It felt rich but was actually a little lean. We replaced the #45 pilot jet with a #48 and completely eliminated the stumble. Changing the pilot jet proved a lot easier than lowering the needle; the float bowl is held on with only two screws, with the right size stubby screw driver it can be

removed with the carb on the bike.

We took the XR on a two-day, 400-mi. trip through Baja California’s deserts and mountains. Getting gas is always chancy in Baja and this trip was normal: several places we usually stop were out of gas or were closed. With the XR, no problem. It consistently went 100 mi. between fillups. Both riders (one on an IT490) are desert experts so a person who rides with more caution could get significantly farther on the tankful. The new jetting got rid of most of the hard starting problems with the engine hot. As long as the throttle isn’t turned as the bike is kicked, it’ll fire up with one or two brisk kicks. We soon learned to use the hand compression lever if the bike was kicked more than three times and didn’t start. Pull the compression lever, turn the throttle wide open, kick the engine through twice, let the lever out, close the throttle completely and kick hard. It’ll start right up.

The XR’s spread of useful power was surprising even to riders who have owned and tested four-stroke Singles for years. It’s smooth at idle, no surprise. It pulls in the mid range, no surprise. And it also makes good power at the top of the scale, which is a surprise. It’s also an occasional excess. At high revs the back tire breaks loose and dances around as it grabs and loses traction. Keep the revs down and the tire hooks up, giving more acceleration or climbing ability, while at the same time you don't have to shift up or down if you’re busy with other things, like steering. The engine will work at the speed it’s at. Which makes it less tiring in the woods than any enduro bike we can recall.

The excellent suspension also eases the rider’s job. With 11-in. of front wheel travel, the forks soak up large bumps— we bottomed the front end once in 950 mi. of riding—and once the fork seals were broken in, at about 500 mi. the forks worked on small bumps as well. The rear suspension offers only (only!

how things change.) 10.6 in. of wheel travel but couldn’t be faulted. Best settings for our crew were rebound damping as delivered, compression damping two clicks softer than stock. If the rear wheel bottomed, no one felt it. The back is very smooth through all kinds of terrain. The XR350R doesn’t cross a series of whoops as well as the ’83 CR480R, due to the XR’s shorter wheelbase. It goes through straight but there is a definite rocking, pogo sensation. Speed and control aren’t affected but the rider is aware of it. Remember this is a woods bike, not a motocrosser or desert racer.

The 350 engine fits the woods concept well. From a stop to 60 mph indicated, the XR is quick. We ran informal drag races with it against the newest Suzuki RM250, Yamaha YZ250 and KTM 250MXC and darned if the four-stroke playbike didn’t stay right with the racers, even when the riders traded bikes. From 60 up the two-strokes pulled away, as we expected. Best we saw on the XR’s speedometer was 73 or 74. Call it an honest 70, the last 10 mph of which comes up mighty slowly.

One of the best things about the XR is its light, agile feel. No one thought it felt as heavy as it weighed, (265 lb. with a half tank of gas). Honda has done a marvelous job of keeping the weight low and of course, the steep steering rake and short wheelbase helps mask the weight. On one of our outings we had our test KTM 250MXC enduro bike along for comparison. The KTM weighs 18 lb. less than the XR350. All our testers thought the XR felt lighter.

Honda has done a great job of prototyping and designing the XR350. Even so, a couple of things are less than ideal. If the clutch is released with the transmission in any gear but first, the clutch will make strange noises and its action can be felt in the clutch lever. With six-speeds it’s easy to think the bike is in first when it’s actually in second. We’d like to see a six-spring pressure

plate instead of the four-spring. Adjusting the clutch cable isn’t as easy as it should be either, the cable is equipped with a center adjuster which is good, but the adjuster is placed so close to the clutch lever bracket adjuster the lever’s slip cover can’t slide far enough to get a clear shot. A small complaint, to be sure. Another, one not noticed by all the test riders, was a strange feeling that the chain was sawing through the frame when the engine was operated at a low speed with the transmission in a high gear. We’ve noticed this on past XRs and have never been able to exactly pinpoint the cause. It may be final drive chain vibration at certain combination of engine speeds.

Our XR350 proved reliable. Our only problem (except for the carb jetting and the ones at dealers may already be fixed) was a clutch that started slipping slightly when the bike had about 800 mi. on it. It wasn’t much but we wanted to fix it. A call to AÍ Baker R&D (714-244-5425) was all it took. He already had stiffer clutch springs in stock. The new springs cured the slip and didn’t make the clutch lever any harder to pull. Otherwise nothing needed repairing or replacing. The O-ring final drive chain was adjusted after the first 100 mi. of break-in and hasn’t needed it since. And it hasn’t been lubed once! Since the O-rings keep grease in, dirt out, there’s little reason to oil it. Even the tires are lasting well. The front is in great shape yet. The rear is about ready for replacement.

We only had one test rider who didn’t like the nifty XR350. He had praise for many of the XR350’s virtues but simply prefers two-strokes. Everyone else thought the XR350 was one of the most fun bikes they had ever ridden. But saying the XR is just fun doesn’t give it due credit. The XR350 is also deadly serious as a woods enduro bike. Don’t be surprised if you read about someone winning a woods enduro overall on an XR350R. 0

HONDA

XR350R

SPECIFICATIONS

$1998