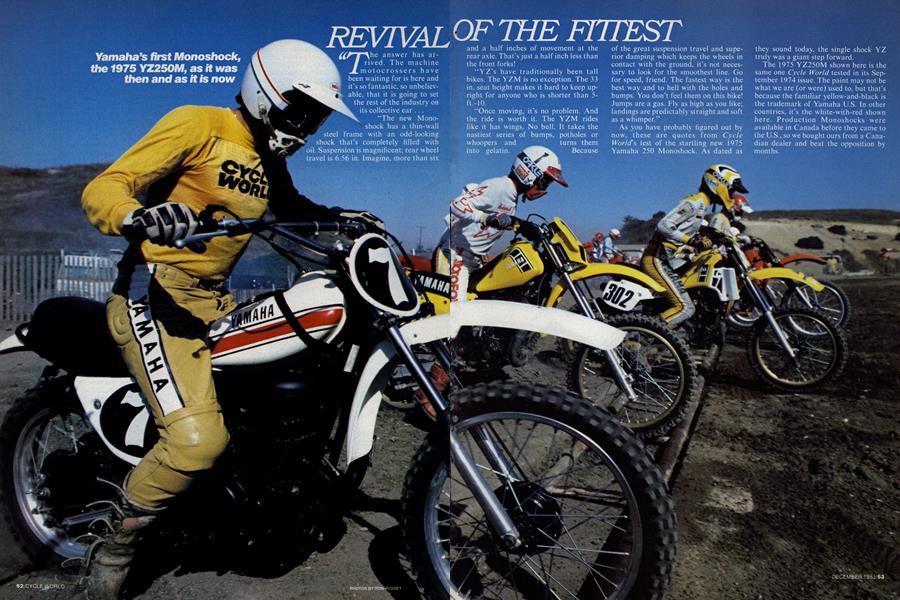

REVIVAL OF THE FITTEST

Yamaha’s first Monoshock, the 1975 YZ250M, as it was then and as it is now

The answer has arrived. The machine motocrossers have been waiting for is here and it's so fantastic, so unbelievable, that it is going to set the rest of the industry on its collective ear. .

“The new Mono-shock has a thin-wall steel frame with an odd-looking shock that’s completely filled with oil. Suspension is magnificent; rear wheel travel is 6.56 in. Imagine, more than six and a half inches of movement at the rear axle. That's just a half inch less than the front forks!

“YZ’s have traditionally been tall bikes. The YZM is no exception. The 33 in. seat height makes it hard to keep upright for anyone who is shorter than 5ft.-10.

“Once moving, it’s no problem. And the ride is worth it. The YZM rides like it has wings. No bull. It takes the nastiest series of bumps, potholes or whoopers and . turns them into gelatin. Because of the great suspension travel and superior damping which keeps the wheels in contact with the ground, it’s not necessary to look for the smoothest line. Go for speed, friend. The fastest way is the best way and to hell with the holes and bumps. You don’t feel them on this bike! Jumps are a gas. Fly as high as you like; landings are predictably straight and soft as a whimper.”

As you have probably figured out by now, these are quotes from Cycle Worlds test of the startling new Í975 Yamaha 250 Monoshock. As dated as they sound today, the single shock YZ truly was a giant step forward.

The 1975 YZ250M shown here is the same one Cycle World tested in its September 1974 issue. The paint may not be what we are (or were) used to, but that’s because the familiar yellow-and-black is the trademark of Yamaha U.S. In other countries, it’s the white-with-red shown here. Production Monoshocks were available in Canada before they came to the U.S., so we bought ours from a Canadian dealer and beat the opposition by months.

Good journalism, questionable business practice. We (and parent CBS) own the bike. We had it on display in our lobby until one day it looked so good and so obsolete at the same time, we decided to learn just how much things have (or haven't) changed. A carb overhaul, a new dry-side crank seal and a new piston ring and the first single shock YZ was running again.

But before the visit, a little history.

The “YZ” designation began as the factory code for the production racer. Yamaha’s first real mass-market motocrossers were labeled MX or SC, but in 1974 Yamaha introduced the YZ250, a near replica of the '72 team machines, and priced accordingly; $ 1 836 versus $1145 for the Honda CR250M. Meanwhile Yamaha had noticed a single-shock rear suspension developed by a European privateer. The basic idea wasn't new but it was different and did seem to offer an advantage over the conventional dual shocks which in turn were even less new' in principle—so Yamaha bought the rights and developed the single shock and won with it. At the very top level.

Even so, nobody suspected the customer motocrossers would move as fast, as far as did the YZM, even at the stillwhopping price of $ 1850.

The single rear shock was the center of attention, although nobody really was sure they could use that much wheel

travel. The total bike shouted Racer! The forks were trimmed, virtually every surface was drilled for lightness, the side covers, seat base, number plates and airbox were fiberglass, the wheel rims, the brake arms, the rear static arm, the levers, even the fuel tank, all light and expensive aluminum. Magnesium was just too expensive for production racers, but the clutch cover, mag cover, countershaft sprocket cover and brake backing plates were magnesium. Will the tricks never stop?

A huge, 34mm Mikuni carburetor fed premixed gas through a six-petal reed. The cylinder was aluminum with a chrome-plated bore, just like the factory guys had. Even the pipe and silencer were exotic; the pipe had a big center section that wound over the top of the engine, its two major sections held together with springs. It was mounted to the bike with rubber and steel hangers and was strapped to the frame with a spring that surrounded the pipe's belly. A complementary silencer about the size of a large screwdriver handle, and about as effective, was mounted to the end of the pipe’s stinger.

Eight short model years later, the bike that startled the motorcycle press (and other manufacturers), and started the switch to single shock rear suspensions, still stands out as a unique bike. Comparing some of the 1975 YZM’s features to an '83 YZ250 is fun.

As you can see, the '83 bears no resemblence to the '75. And comparing figures doesn't start to point out the differences. Today’s motocrossers are not only longer and taller and lighter. All of today’s motocrossers have longer and stronger swing arms, beefy fork stanchion tubes, chrome-moly steel frames, larger and stronger spokes, smaller and stronger hubs, shorter gas tanks, longer seats that extend over the rear of the tank, watercooling, double-leading shoe front brakes (or single hydraulic discs in some cases), suspension systems with adjustable damping, more efficient airboxes and filters, engines with a lot more power and broader torque curves and on and on . . .

The unbelieveable, so fantastic suspension travel of ’75 is comparable to the 60cc beginner motocrossers kids are riding today. No modern mx bike has less than 11.2 in. of fork travel, and many ’83 MXers have close to 13 in. of rear wheel travel. Some also have seat heights over 39 in.

Riding the ultimate motocrosser of yesteryear is both fun and enlightening: A quick zip down the street and back had us thinking the bike awfully slow. As a few more careful miles were put on, the YZM got faster but still felt like a slug compared to present day motocrossers. Knowing seat-of-the-pants power impressions are usually wrong, we took the bike to a local motocross race. Our best pro racer dressed in gear appropriate to the year of the bike and lined up with the 250 amateurs. We wanted pictures of the bike being smoked off the start line. Wouldn’t you know it, the YZ250M got the hole shot! And, to get the pictures we wanted, our rider had to back off the throttle. After he was sure he was last and in a cloud of dust, he again turned the throttle to full. At the top of the start hill he was about 14th out of 20 starters. By gassing the YZ and taking the wide outside line in the first turn, then holding the throttle to its stop down the hill, he entered the second turn in fifth place. People were pointing and laughing and wondering who was the clown with the old bike, and how he got so fast. The other competitors had a good laugh when the YZ lined up at start gate too. Now, many weren’t laughing. How could any antique bike beat them? Anyway, our rider passed fourth, a guy on a new Honda CR250R, and the racer couldn’t stand it. He turned the. throttle to its stop and moved his body into a racing crouch, just before he crashed.

The YZ250M’s suspension felt too stiff and springy before the race. Two laps into the race the rear shock, and the forks, had heated to the point of fade and the suspension worked well (for its limited travel). As dated as the bike’s numbers are, it still goes straight over the bumps and jumps, never kicking sideways. Of course it bottoms badly with such limited wheel travel but otherwise, it handles well. The low seat and engine height make corners easy; the tires stick and there is no tendency to high-side or stand up but the footpegs, shift lever and brake pedal drag badly. The rear brake ped-al grounded and bent under the footpeg before the end of the first lap.

Our intentions were to race the YZ for a lap or two, then quit so we didn’t ruin such a rare old piece, but the rider was having so much fun he went eight laps. Spectators were really enjoying it too. Most were waving and taking pictures, especially at the double jump where our man was the only one double jumping. The petcock came loose on the eighth lap, ending the fun when the bike ran out of gas. It was surprising to see the old bike, with its steer-horn bars and short suspension, circulating with the newest motocrossers. It was more surprising to see it outrun newer bikes. In this case, the difference between a pro-class rider and an amateur just about equalled the difference of eight years technological progress. In a pro race, it would surely have been at the back of the pack.

That’s what eight years of progress are supposed to do. It has made motorcycles that are faster and easier to ride fast. That progress has come in spurts. After the YZ came bikes with more suspension travel. Then the longer travel meant the forks were flexing, so stronger fork tubes were used. And to take advantage of the longer travel in back, linkage-controlled single shocks have become standard. Liquid cooling has given longer engine life and more consistent power during races.

It was good to get back on the old YZ, to feel dirt under both feet occasionally. It was a constant reminder that ultimates don’t exist in motorcycles. As far ahead of the competition as it was, it was outdated a couple of years after it came out.

Time stands still for no motorcycle, but it does look kindly on pioneers like

the YZM250. E

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

December 1983 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

December 1983 -

Departments

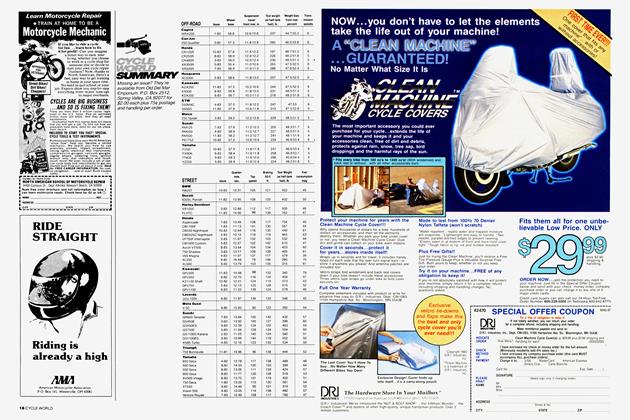

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

December 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

December 1983 -

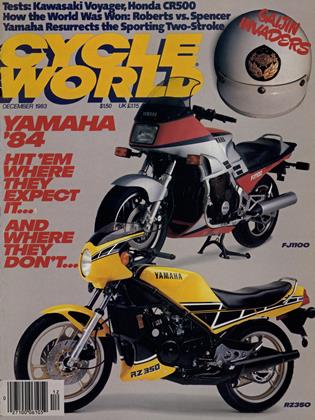

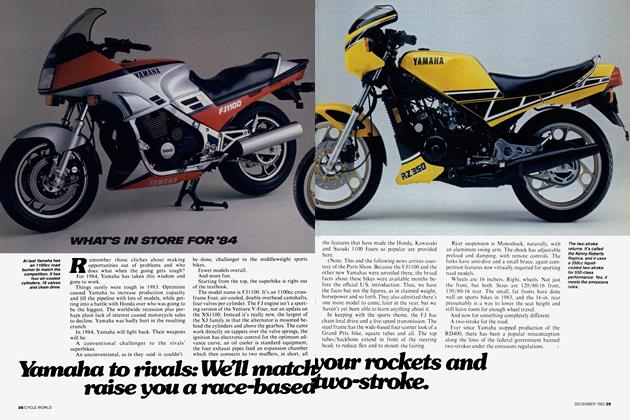

What's In Store For '84

What's In Store For '84Yamaha To Rivals: We'll Match Your Rockets And Raise You A Race-Based Two-Stroke.

December 1983 -

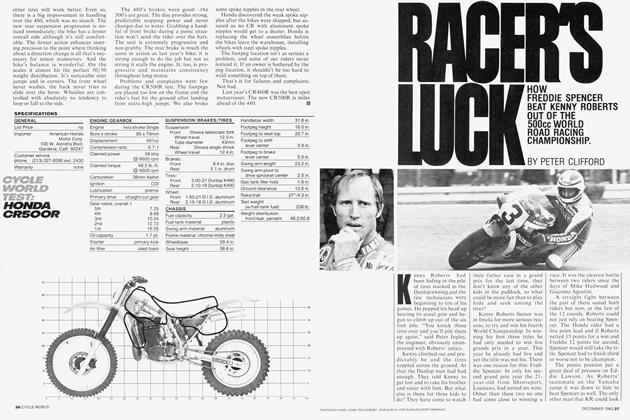

Competition

CompetitionRacer's Luck

December 1983 By Peter Clifford