ROUNDUP

CYCLE WORLD

LAWYERS

An awkward dispute involving the American Motorcyclist Association and some of the major motorcycle manufacturers has disrupted this year’s TransUSA motocross series. That’s the easy part of the report. From there it gets sticky.

A little history is needed to put things in perspective. Originally the TransUSA series was an end-of-season motocross race for European and American riders, a way of getting the best riders in the world to this country. Now that the best motocross riders in the world regularly race in this country, because they are from this country, the Trans-USA series has become less important.

At the same time, the interest in traditional outdoor motocross races has been fading. Stadium motocross has become more popular. One of the reasons is all the top riders compete against each other, all on the same size bikes. The current system of separate national champions for each engine size, plus a Supercross champion and maybe a Trans-USA champion has created a confusing sport to follow.

That brings us up to early in 1982. Everyone involved in professional motocross racing realized that interest was fading for the current structure. A proposal to reduce the status of 125cc racing to a junior class and have the top riders compete aboard both 250s and open class bikes was drawn up. It would also eliminate the Trans-USA series in 1983. All the top riders would get to compete for one national championship. Great, everyone said, let’s do it. And so the AMA Board of Trustees voted unanimously for the new format on the recommendation of all involved parties.

Among the AMA Board of Trustees are representatives of all the major motorcycle manufacturers. Class B members, they are called. About a month after the new motocross format was adopted the AMA received a letter signed by K. Fukatsu of Honda, M. Shibuya of Yamaha and Y. Masuda of Suzuki protesting the new motocross format. They suggested reducing the number of national motocross races and retaining separate championships for the different size bikes. A later letter from the three manufacturers suggested retaining separate national championships and crowning a grand national champion whose best finishes in supercross and 250cc or 500cc races gave him the most points.

continued on page 22

A special board meeting called by the three manufacturers upheld the new AMA rules again, but not unanimously. Then on Aug. 20 each of the three companies sent letters to the AMA withdrawing its riders from the Trans-USA series. At the same time, Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki announced its riders would be competing in another series called the Trans-Cal. It just so happened that this new CMC-sanctioned series would occur on the same five dates that the Trans-USA races were scheduled. So the three major motocross teams had been pulled from a series that was organized after the teams committed themselves to racing in the series.

The next major event in this long chain of unusual actions is a $15 million lawsuit filed by the AMA against Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki. The suit, filed Sept. 23, charges the three manufacturers with conspiracy in restraint of trade, conspiracy to monopolize, conspiracy to breach fiduciary duty and conspiracy to interfere with contractual and advantageous business relationships. It asks for a temporary restraining order and an injunction prohibiting the factories from entering its riders in the competing Trans-Cal series, plus compensation and punitive damages of $15 million.

That brings us up to date. Where the mess will go from here, we can’t predict, but will offer comment.

First, the Trans-USA series has outlived its usefulness as an international motocross event. The three motocross teams involved can take their bikes and riders and go home without risking a loss of publicity. But to pull the teams after committing the riders to the series is shoddy.

Next, the factories have valid concerns about the scheduling of a long season of races. More careful scheduling could no doubt reduce the travel costs for not only factories, but privateers, too.

What the dispute may eventually turn into is a battle over control of racing. The factories want the series organized to promote their products. The racers want it organized for their convenience and profit, and likewise the promoters want to make the most money on their investment. The AMA must represent the interests of of all these groups, plus the fans who are also members. This is a tough job because the interests of the groups conflict. The only way it will work is if all the parties involved follow the rules and abide by the majority decision.

SOUNDING OFF

When the Environmental Protection Agency first proposed motorcycle sound level regulations, the motorcycle manufacturers were encouraged. They wanted a federal noise law. The reason is the conflicting noise laws adopted by various states. Now that the federal noise standard goes into effect Jan. 1, 1983, many states with conflicting standards have modified their laws to conform with the federal standard.

In order to make life easier for motorcycle companies, Oregon, California, Maryland, Florida and the city of Chicago have changed their sound laws that would have established lower sound levels for motorcycles built before the federal law takes effect.

Beginning the first of January, street bikes will be limited to 83 dB (A). Mopeds are limited to 70 decibels, offroad bikes under 170cc are limited to 83 decibels and over 170cc the limit is 86. In 1986 the law sets a limit of 80 db (A) for street bikes and off-road bikes under 170cc. The limit for dirt bikes 170cc and over will drop to 82. continued on page 26

CHANGING NAMES

Fans of Peter Egan may be sorry to learn that he has deserted Cycle World for an office with a window and a chance to write about cars for Road & Track magazine. The good news is Wade Roberts, his replacement.

Wade comes most recently from the Houston Chronicle where he has been a feature writer. His motorcycles include a Triumph Bonneville, BSA 650 and Harley-Davidson XLCR, so he is a motorcycling romantic as well as a talented story teller.

GETTING SAFER

Motorcycling got safer last year, but it didn’t get more popular. The numbers are finally in for 1981, compiled by the American Motorcyclist Association and the Motorcycle Safety Foundation. Registrations of street legal motorcycles dropped 1.02 percent to 5,623,336 and accidents declined 1.2 percent to 175,022. Fatal motorcycle accidents decreased 4.96 percent to 4844. This is the first decline in fatalities recorded since 1976, according to the AMA.

Motorcycle statistics have not been easy to collect. Not all states collect statistics the same, some including mopeds in the lists of motorcycles and others that may include non-motorcyclists involved in motorcycle accidents. The AMA and MSF forms this year are more detailed. According to Fegislative Affairs Manager Gary Winn, “We discovered that there are many accidents involving unregistered motorcycles, especially dirt bikes, that are included in the totals. This tends to unfairly weight the ratio of accidents to registrations. For instance, 1 1 percent of Alabama’s recorded motorcyclist fatalities involved unregistered motorcycles. These are figures and information we never had before.”

The year 1980 was the peak year for fatalities and registrations, with 5097 motorcyclists killed, from 5,681,479 registered.

WHO WE ARE

Once again, the Motorcycle Industry Council has published the Motorcycle Statistical Annual, a compilation of facts about motorcycles and the people who ride them. The 1982 Annual is much like previous annuals in the information provided, but updates this information for the 1981 model year.

While all the facts in the book fill 46 pages, some selected figures might be of interest. There are 7.3 million motorcycles in use in this country, 52.2 percent of them road-only bikes, 22.6 percent offroad only and 25.2 percent dual purpose. The five states with the most motorcycles are California, Texas, Michigan, Ohio and Illinois in that order. Surprisingly, the states with the most motorcycles per 100 residents are all snow-belt states. Alaska tops the list with 7.4 motorcycles per 100 population, followed by Idaho at 7.2, Montana at 7.1, Iowa at 6.6 and North Dakota at 6.5. The lowest penetration of motorcycles is in Washington, D.C. with 0.4 per 100. New York, New Jersey and Massachusetts all have figures under 2 per 100.

In 1981 1,225,000 motorcycles were imported and 1,045,000 were registered to new owners. The MIC estimates there are 540,000 motorcycles in warehouses and another 550,000 motorcycles at dealers. Honda sold more new motorcycles than any other manufacturer, taking 37.5 percent of the new motorcycle sales. Yamaha had 25.4 percent, Kawasaki 16.2 percent, Suzuki 14 percent and Harley-Davidson 5.2 percent.

An average motorcyclist rides 2384 mi. a year. Street bikes average 2732 mi. and off road bikes average 480 mi. The average cost of owning and operating a mid-size street bike is $748, compared to $3116 for a mid-size car.

About 92 percent of the motorcyclists are male. The median age is 24, with six years riding experience on 3.1 motorcycles. The median rider has an annual household income of $17,500.

Copies of the 1982 Motorcycle Statistical Annual are available from the MIC, Research and Statistics Department, 2400 Michelson Drive, Suite 110, Irvine, Calif. 92715. Cost is $25.

FUTURE SMOG

Only California motorcycles would be affected, but the factories have protested a California Air Resources Board ruling that would lower the hydrocarbon emission standard for motorcycles to 1 gm/kg for 1984.

The standard, as proposed, could result in the installation of catalytic converters on some motorcycles, according to the Motorcycle Industry Council. Estimates of the catalyst cost range from $176 to $385. Motorcycles larger than 280cc would be affected by the ruling. 3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

December 1982 -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1982 -

Features

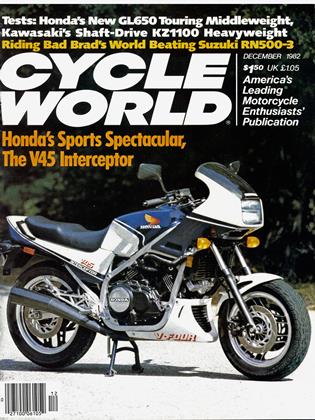

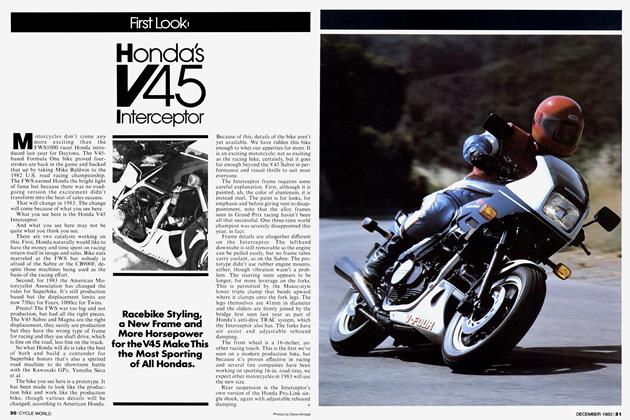

FeaturesFirst Look: Honda's V45 Interceptor

December 1982 -

Evaluations

EvaluationsHonda Silver Wing Interstate Package

December 1982 -

Features

FeaturesElevator Syndrome Part Ii

December 1982 By Steve Anderson -

Features

FeaturesHarley-Davidson For 1983

December 1982