AUTOMATICALLY FASTER

CYCLE WORLD ROUNDUP

Automatic transmissions, at least the things called automatic transmissions, haven’t had much effect on motorcycles in the several years automatic transmissioned motorcycles have been produced. This month another automatic transmissioned motorcycle, the Suzuki GS450 Automatic, joins the lineup. It’s a very nice motorcycle we are still riding because it works well and is somehow fun to ride, but it isn’t likely to put the clutch manufacturers out of business.

This doesn’t mean friction clutches and straight-cut gears engaged by dog clutches are the only ways of transmitting power. Lots of other methods have been tried and more will be built. A recent study for the Department of Energy catalogued 10 alternates known as continuously variable transmissions, or CVT for short.

CVTs are a marvelous way to transmit power because an engine can be operated at its power peak or at the lowest possible engine speed or whatever other operating

speed the designers want. And the engine can stay at the optimum speed while the transmission continuously changes the gear ratio to take advantage of the engine’s most efficient, or most powerful operating speed. A good CVT can provide both quicker acceleration and better fuel mileage than a conventional transmission, and it can do it without a clutch lever or a shift lever.

Once upon a time there was a CVTequipped motorcycle. Sort of. It was the Salsbury, a giant motorscooter produced in California about 30 years ago, and it used a CVT with a belt operating between a pair of variable diameter pulleys, the kind that spread apart in the middle so the belt can slide down toward the spindle, forming a smaller pulley.

The Salsbury, according to Indian medicine man Bob Stark who is restoring a few of them, was a mighty fine scooter. It was faster than any cars of its day, at least in acceleration. And this was with a none-too-big four-stroke engine that

looked like something from a Cushman. Salsbury transmissions are still around, most often used in snowmobiles, and various manufacturers are still paying licensing costs to the owners of the Salsbury patents to produce the transmissions.

Salsbury systems were also used on the Rokon automatics.

On another front there’s the van Doorne CVT, the most recent variable transmission designed for automotive applications. Dr. H.J. van Doorne was one of the founders of the DAF, a car made in the Netherlands that has had a CVT. After the car design was sold to Volvo he started another company that has developed an improved CVT, using a steel belt between two variable diameter pulleys. Although the van Doorne transmission will be used in automobiles and trucks, it could be used in motorcycles, too. Testing has shown the van Doorne transmission to improve fuel economy up to 20 percent over a standard five-speed transmission and to improve acceleration about 2 percent. Efficiency of the unit is around 90 percent, which is slightly less than a normal gearbox, but because the engine can operate at optimum speeds for power or economy, depending on the control unit, overall performance is improved.

Most of the work on CVTs is being done to improve fuel economy on cars, not to improve performance. The comparisons being made are with automatic transmissions, which are well developed, expensive and relatively heavy. Customers have demanded automatic transmissions in cars and the manufacturers are looking at the CVTs as types of shiftless transmissions with better efficiency.

Continuously variable transmissions may not find their way into motorcycles any time soon. Other examples of automatic transmissions in motorcycles

haven’t gone over well. Of course the current automatics, except for the Husky, which really is an automatic, have sacrificed performance for the automatic clutch.

Just where the performance goes is a bit of a surprise to those who have ridden the latest automatic. The Suzuki Automatic has become quite popular around the office. As the test explains, it runs well and has no real shortcomings. And on the lunchtime sprints to the hamburger stand, it competes well against a variety of 550s and 650s, especially when ridden by John “Mad Dog” Ulrich. Under normal street conditions the Automatic gives nothing away to the larger bikes. But when measuring performance at the dragstrip, it turns out to lose most of its performance off the line. Getting to 10 or 20 mph takes longer than it does on the standard shift Suzuki, but only when

the normal model is wound to the redline and the clutch carefully released (abusively slipped). Not even a pack of lunchstarved journalists ride this way from every stoplight, so the Automatic can easily keep up with the bikes ridden in a more normal manner. The Automatic is. more easily ridden hard, with tricks like the kill-switch speed shift becoming normal riding technique, and the local traffic cops are less likely to notice it too.

Of course the only way the CVT will invade motorcycling is through racing. As the racing snowmobiles have demonstrated, extraordinary specific power outputs can be made useable with a CVT keeping the engine on the boil.

Too bad the Honda NR500 ended up with such a useable powerband. That’s just the kind of machine, made by just the kind of people, that could make a CVT work.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

November 1982 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1982 -

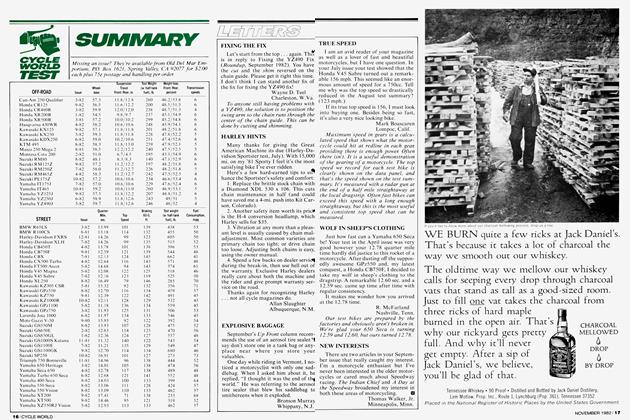

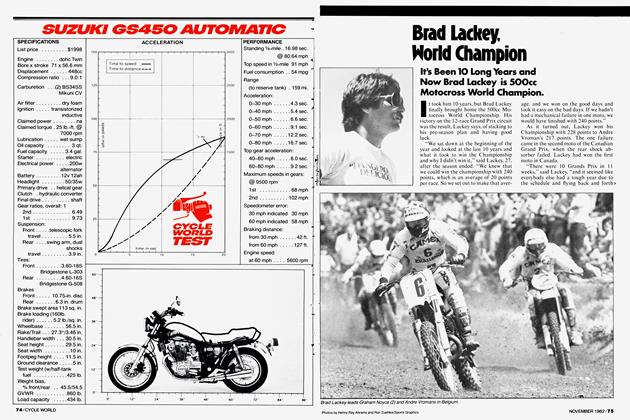

Cycle World Test

Cycle World TestSummary

November 1982 -

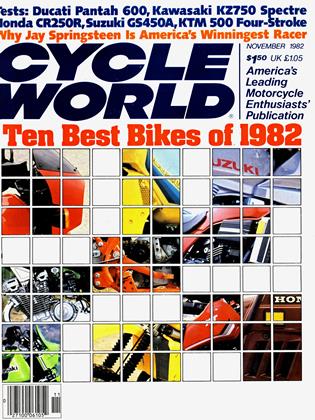

Ten Best Bikes of 1982

Ten Best Bikes of 1982Even When They're All Good, Some Are Better.

November 1982 -

Competition

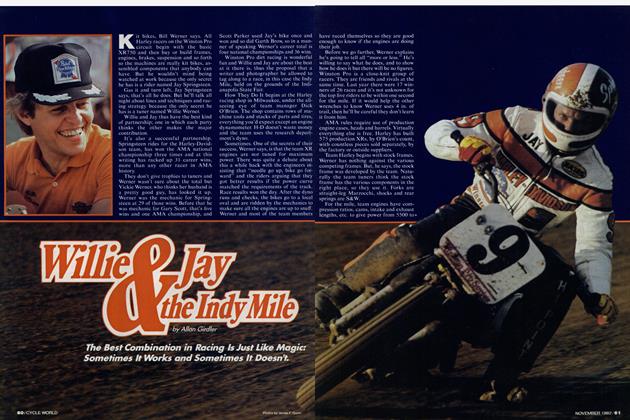

CompetitionWillie & Jay the Indy Mile

November 1982 By Allan Girdler -

Competition

CompetitionBrad Lackey, World Champion

November 1982