UP THROUGH THE RANKS

20 CYCLE WORLD YEARS

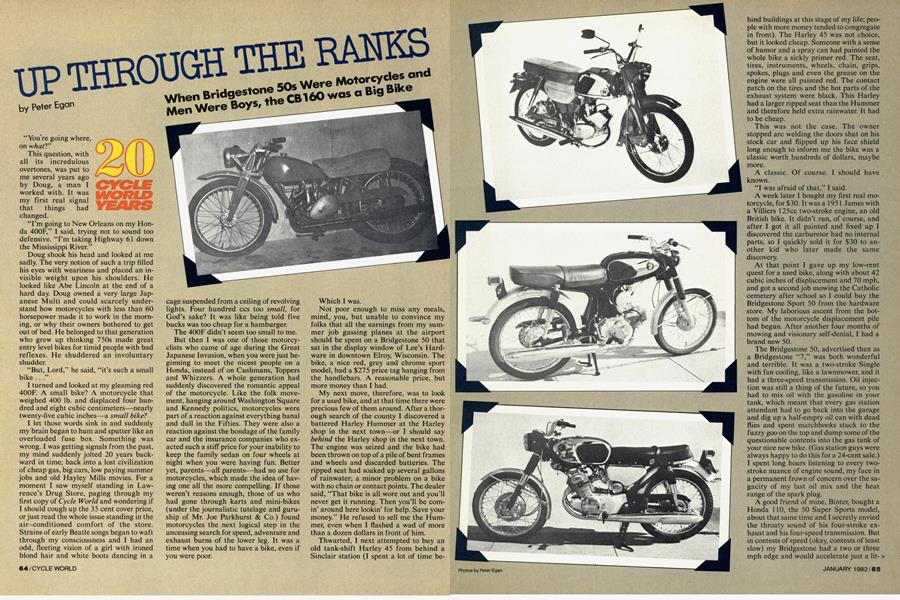

When Bridgestone 50s Were Motorcycles and Men Were Boys, the CB160 was a Big Bike

Peter Egan

“You’re going where, on what?"

This question, with all its incredulous overtones, was put to me several years ago by Doug, a man I worked with. It was my first real signal that things had changed.

“I’m going to New Orleans on my Honda 400F,” I said, trying not to sound too defensive. “I’m taking Highway 61 down the Mississippi River.”

Doug shook his head and looked at me sadly. The very notion of such a trip filled his eyes with weariness and placed an invisible weight upon his shoulders. He looked like Abe Lincoln at the end of a hard day. Doug owned a very large Japanese Multi and could scarcely understand how motorcycles with less than 60 horsepower made it to work in the morning, or why their owners bothered to get out of bed. He belonged to that generation who grew up thinking 750s made great entry level bikes for timid people with bad reflexes. He shuddered an involuntary shudder.

“But, Lord,” he said, “it’s such a small bike .. .”

I turned and looked at my gleaming red 400F. A small bike? A motorcycle that weighed 400 lb. and displaced four hundred and eight cubic centimeters—nearly twenty-five cubic inches—a small bike?

I let those words sink in and suddenly my brain began to hum and sputter like an overloaded fuse box. Something was wrong. I was getting signals from the past, my mind suddenly jolted 20 years backward in time; back into a lost civilization of cheap gas, big cars, low paying summer jobs and old Hayley Mills movies. For a moment I saw myself standing in Lawrence’s Drug Store, paging through my first copy of Cycle World and wondering if I should cough up the 35 cent cover price, or just read the whole issue standing in the air-conditioned comfort of the store. Strains of early Beatle songs began to waft through my consciousness and I had an odd, fleeting vision of a girl with ironed blond hair and white boots dancing in a cage suspended from a ceiling of revolving lights. Four hundred ccs too small, for God’s sake? It was like being told five bucks was too cheap for a hamburger.

The 400F didn’t seem too small to me.

But then I was one of those motorcyclists who came of age during the Great Japanese Invasion, when you were just beginning to meet the nicest people on a Honda, instead of on Cushmans, Toppers and Whizzers. A whole generation had suddenly discovered the romantic appeal of the motorcycle. Like the folk movement, hanging around Washington Square and Kennedy politics, motorcycles were part of a reaction against everything banal and dull in the Fifties. They were also a reaction against the bondage of the family car and the insurance companies who exacted such a stiff price for your inability to keep the family sedan on four wheels at night when you were having fun. Better yet, parents—all parents—had no use for motorcycles, which made the idea of having one all the more compelling. If those weren’t reasons enough, those of us who had gone through karts and mini-bikes (under the journalistic tutelage and guruship of Mr. Joe Parkhurst & Co.) found motorcycles the next logical step in the unceasing search for speed, adventure and exhaust burns of the lower leg. It was a time when you had to have a bike, even if you were poor.

Which I was.

Not poor enough to miss any meals, mind, you, but unable to convince my folks that all the earnings from my summer job gassing planes at the airport should be spent on a Bridgestone 50 that sat in the display window of Lee’s Hardware in downtown Elroy, Wisconsin. The bike, a nice red, grey and chrome sport model, had a $275 price tag hanging from the handlebars. A reasonable price, but more money than I had.

My next move, therefore, was to look for a used bike, and at that time there were precious few of them around. After a thorough search of the county I discovered a battered Harley Hummer at the Harley shop in the next town—or I should say behind the Harley shop in the next town. The engine was seized and the bike had been thrown on top of a pile of bent frames and wheels and discarded batteries. The ripped seat had soaked up several gallons of rainwater; a minor problem on a bike with no chain or contact points. The dealer said, “That bike is all wore out and you’ll never get it running. Then you’ll be cornin’ around here lookin’ for help. Save your money.” He refused to sell me the Hummer, even when I flashed a wad of more than a dozen dollars in front of him.

Thwarted, I next attempted to buy an old tank-shift Harley 45 from behind a Sinclair station (I spent a lot of time behind buildings at this stage of my life; people with more money tended to congregate in front). The Harley 45 was not choice, but it looked cheap. Someone with a sense of humor and a spray can had painted the whole bike a sickly primer red. The seat, tires, instruments, wheels, chain, grips, spokes, plugs and even the grease on the engine were all painted red. The contact patch on the tires and the hot parts of the exhaust system were black. This Harley had a larger ripped seat than the Hummer and therefore held extra rainwater. It had to be cheap.

This was not the case. The owner stopped arc welding the doors shut on his stock car and flipped up his face shield long enough to inform me the bike was a classic worth hundreds of dollars, maybe more.

A classic. Of course. I should have known.

“I was afraid of that,” I said.

A week later I bought my first real motorcycle, for $30. It was a 1951 James with a Villiers 125cc two-stroke engine, an old British bike. It didn’t run, of course, and after I got it all painted and fixed up I discovered the carburetor had no internal parts, so I quickly sold it for $30 to another kid who later made the same discovery.

At that point I gave up my low-rent quest for a used bike, along with about 42 cubic inches of displacement and 70 mph, and got a second job mowing the Catholic cemetery after school so I could buy the Bridgestone Sport 50 from the hardware store. My laborious ascent from the bottom of the motorcycle displacement pile had begun. After another four months of mowing and visionary self-denial, I had a brand new 50.

The Bridgestone 50, advertised then as a Bridgestone ”7,” was both wonderful and terrible. It was a two-stroke Single with fan cooling, like a lawnmower, and it had a three-speed transmission. Oil injection was still a thing of the future, so you had to mix oil with the gasoline in your tank, which meant that every gas station attendant had to go back into the garage and dig up a half-empty oil can with dead flies and spent matchbooks stuck to the fuzzy goo on the top and dump some of the questionable contents into the gas tank of your nice new bike. (Gas station guys were always happy to do this for a 24-cent sale.)

I spent long hours listening to every twostroke nuance of engine sound, my face in a permanent frown of concern over the sagacity of my last oil mix and the heat range of the spark plug.

A good friend of mine, Binter, bought a Honda 110, the 50 Super Sports model, about that same time and I secretly envied the throaty sound of his four-stroke exhaust and his four-speed transmission. But in contests of speed (okay, contests of least slow) my Bridgestone had a two or three mph edge and would accelerate just a lit> tie faster. We took this pair of bikes on a weekend trip to a northern campground and gave rides to two underage girls from Chicago. They were really impressed with our bikes, until their parents returned from the outdoor theater.

The Bridgestone was a sport model with a normal tank and seat like a motorcycle, which was better than a step-through with plastic chaps, but I was bothered by the tank emblems, which said “BS.” The BS was, I believe, a poorly conceived attempt to emulate the British infatuation with lettered abbreviations in motorcycle names and to make the bike seem less Japanese. I finally got tired of explaining to friends and relatives why my motorcycle said BS on the tank, so I turned the emblems upside down, making them nearly unreadable. Then people asked why my BS emblems were upside down. It made me wish I’d bought a Triumph.

I rode the 50 everywhere, even to visit my girlfriend who lived 12 mi. away, riding flat out at 36 mph nearly all the time. When I pulled into my girlfriend’s driveway and her parents were there it made me glad I’d bought the Bridgestone instead of the red Harley 45. The Harley would have driven them to question my intentions and then lock their daughter in her room, but when they saw the 50 they assumed I was harmless. The Bridgestone made me look nice, like a member of the Kingston Trio or the Junior Jaycees. It should have been sold with a matching set of penny loafers and cut-offs.

The 50 was so slow that when I came home from my girlfriend’s house late at night I was forced to ride on gravel country roads so I wouldn’t be rear-ended by a haywagon with no lights or a drunk in search of a lost driveway. On these moonlit, backroad trips I was bitten by many dogs who discovered they could both trot and chew at the same time.

It was only a matter of time before somebody broke through the 50cc barrier. It happened at my high school. A farm boy who’d made a killing, so to speak, by selling his 4-H Blue Ribbon heifer bought himself a Honda CL 160, the street scrambler model, and everybody thought he was God. He was known to travel at actual highway speeds and above, in the company of cars. He made a point each night of passing the school bus on his way home for chores; this was executed at top speed, elbows out and chin on the tank, with an exaggerated swerve, as if the school bus were nothing more than a stray cat or a piece of road debris that had suddenly appeared on the pavement, causing a close call. He allowed no one else to ride the bike, but we all did a lot of speculating on the sheer power of the thing: “Can you imagine, more than three times as fast as a fifty ...” and so on.

We knew of people who also rode Harleys and Triumphs and BMWs and BSAs then, but they were off in another universe of unattainable wealth—doctors, factory workers, auto mechanics, college professors and high school dropouts; all members of that elite who got to spend what they earned instead of Saving For College. These bikes were so far out of the question most of us could only lust, but never buy. For the time being we were locked securely into the Japanese small displacement ladder. We were the frowning faces at the bottom end of the totem pole.

The following year, through a series of sales and machinations that involved a Fender DeLuxe Reverb amplifier, my Bridgestone and a pair of barely used football cleats, I got myself a real motorcycle. A Honda Super 90. I got the bike with 6000 mi. on the odometer and dents all over the tank and German cross decals plastered on every decal bearing surface. After buying the bike I rode it around the corner and immediately scraped the crosses off with a penknife. Strafing trains wasn’t part of my riding style.

The effect of those 40 extra cubic centimeters was incredible. The bike would go between 55 and 60 mph, depending on the wind, with no trouble, and on the weekends I was able to visit a girlfriend who lived 60 mi. away, in the exotic Eastern Wisconsin city of Wautoma. The prestige of owning this large bike allowed me to purchase and wear a Bell TX-500 helmet and goggles without subjecting myself to the ridicule suffered by riders of 50s, who by wearing helmets had the audacity to suggest they were in some kind of danger. Even my girlfriend thought the 90 was a big bike. It would pull us up a hill in second gear and fly along the highway at speeds that brought tears to your eyes. On spring weekends I sometimes rode the 90 home from college, a trip of 85 mi. that cost about 28 cents each way. Even then I thought that was surprisingly cheap; a denial of some physical law that I would probably pay for later.

I sold the 90 to a kid the following year and bought a used Honda CB160 from another kid. This bike cost $200 and came with a helmet of such low quality it could cause head injuries while sitting in the closet. It was a ’66 with 10,000 mi. on it and it needed a new clutch, which I installed at a cost of $8 the day I bought the bike.

With a 160 you could go anywhere— around the world if you wanted to. A friend of mine, Donnelly, had another giant road-eater, a 305 Honda Dream, and together we took a 3000 mi. journey through Canada in the autumn—one of those Vietnam era scouting trips just before I gave up on the expatriate idea and turned myself in to the draft board.

We rode for three days in a cold blowing rain on the curveless pine tree lined roads of northern Ontario, averaging about 70 mph. Nothing went wrong with either bike, and it never occurred to me the Honda was too small for this kind of trip. I used the 160 as an excuse to buy a new Buco black leather riding jacket, having at last reached the big time. A leather jacket would have drawn jeers on the Super 90, blit it was okay to have one if you owned a big fast Twin like a CB160. By then I had a girlfriend who lived in the north country, several hundred miles away via highway 51, in Wausau, Wisconsin. These visits were no problem for a man with a CB160, a Bell TX-500 and a Buco leather jacket, not to mention a long trailing scarf knitted by same friend.

My parents sold the 160 for me while I was in the Army. Upon my release from that august body I squandered what had been a Triumph 650 fund on three months of riotous living in Europe, not to recover financially until more than a year later when I bought a new 1973 Honda CB350 for $800. (I kept buying Hondas because: (A) they were four-strokes when most other Japanese bikes were two-strokes; (B) I’d lost my taste for crackling engines and oil mixing during the Bridgestone 50 days; (C) I’d never had any trouble with any of the Hondas I’d owned; and (D) they were a lot cheaper than Triumphs and Nortons and other bikes I wanted.)

The CB350 was fast; faster than any car or bike I’d ever owned, and fast enough to amaze and impress friends when you took them for a ride. It had a nice dark green paint scheme and a front disc brake—the first I’d had—and it went just over 100 mph and had a wonderful power surge when the engine came up on cam. I was married by then so my riding mode switched from driven, hectic dashes to far away places to a pattern of fast Sunday morning rides and commuting to work. Feeling firmly established in motorcycling, I went out and bought yet another revered piece of riding garb, a Barbour jacket. The CB350 was a bigger, faster and heavier bike than anything most people in the world ever have an opportunity to ride. But it wasn’t big enough for me.

After nine years of climbing the displacement ladder a few ccs at a time, I finally threw fiscal responsibility to the > wind and bought a Big Bike. A victim of all those gorgeous ads on the inside covers of Cycle World, as well as my own life’s ambition to own a large British Twin, I bought one of the last Norton 850 Interstates ever to sit on a showroom floor. It was 1975, the year the company folded. The Norton looked beautiful, went fast, handled and sounded right. It was also, we discovered on many trips, about as reliable as your maiden aunt—the elderly one who leaves faucets running and thinks all her nieces and nephews, including you, are named Arnold, after her late brother. The one who desperately needs fireproof sheets because she smokes in bed, and is out on bail for backing her Packard into a policeman.

Reliability was not the Norton’s middle name.

Nothing major, mind you. A stuck exhaust valve here and there, a failed clutch and ever-loosening exhaust pipe flanges. Nothing that couldn’t easily be fixed, unless you happened to be in central Montana, hundreds of miles from the nearest known Norton part and 1500 mi. from home. In which case the Norton rode home in a Bekins freight van while you finished the trip by bus. It became apparent that Nortons made wonderful second bikes or sport bikes for occasional use, but were not always the preferred choice for transcontinental runs.

About that time a friend bought a new Honda 400F and I took a ride on it. I’d never considered owning a Four; just didn’t like the idea. Motorcycles were supposed to be simple and light and narrow and Fours seemed complex, heavy and wide. And then there were all those carbs ... But the 400F was relatively light and compact, and if you loved the look and sound of machinery it was hard to resist that motor. It revved in fast, woofy shrieks, like a sewing machine on 5000 volts of wall current. The carbs didn’t go out of adjustment as often as those on my Norton (i.e. between stoplights); in fact they didn’t seem to go out of adjustment at all. Best of all, I soon became convinced, and still believe, the 400F was the best looking motorcycle ever to come out of Japan.

With a heavy heart, as Lyndon Johnson used to say, I sold the Norton for $1100 and happily bought a hardly used red 400F for $900. The difference was spent on a trip to New Orleans and a secondhand set of black Mike Hailwood replica Lewis horsehide road racing leathers. I soon put them to good use by joining WERRA and crashing my 400 in such diverse places as Terre Haute and Gratten, Michigan, a four-stroke underdog in a large field dominated by RD350s and 400s. I did okay, but Sheene and Roberts lost no sleep that season, fearing I would steal their jobs. No Telexed job offers arrived from Kei Carruthers. In bars, pouting European women did not hang on my shoulder and say things like “Pierre, I worry too much for you because you go so fast. . .” You couldn’t have everything.

Since the 400F I’ve wandered up and down the displacement scale with half a dozen other bikes, all bought for different reasons: a ’75 Honda CB750 so I could take a long road trip to Watkins Glen in fast company; A ’67 Triumph Bonneville because I’d wanted one forever; a ’64 Honda 50 stepthrough so I could go touring with a friend who had a racing bicycle; a ’62 Honda 150 Benly Touring because it was such a strange looking period piece; a ’76 RD400 for racing purposes; an ’80 KZ550 ditto; a ’68 Triumph Daytona 500 because it’s a light, nice-running British Twin that looks and sounds like a motorcycle; a ’71 Norton 750 Commando for the same reasons; and a Ducati 900SS because it’s a light, nice-running Italian Twin that looks and sounds like a motorcycle while going 135 mph, and because it’s such a wonderful affront to those twin horrors of our time, Safety and Regulation.

In the meantime I’ve ridden and tested a lot of bikes for the magazine; 1000s, 1100s, and 1300s; Fours, Twins and Sixes; lithe sport bikes and ponderous touring rigs weighing over 700 lb. But I have still been unable to think of the 400F as a small bike. Small, perhaps, in the lean, maneuverable sense, but not too small to ride from Wisconsin to New Orleans or anywhere else where there are roads. For those of us who bought 50s the year Cycle World hit the newsstands, a small motorcycle will always be a machine which is a few mph slower than a lame farm dog with a grudge, but slightly faster than an hour in church.

People who haven’t droned interminably from town to town on 50cc motorcycles will never be able to fully appreciate owning or riding a large displacement bike. How can you comprehend what a GS1100 means if you’ve never made a frenzied high gear assault on a low hill with a Bridgestone 50, chin on tank, only to downshift twice and be humiliated into pulling off on the shoulder to let your Spanish teacher go by in his Rambler?

You can’t.

Indeed, how could you enjoy sipping' Jameson’s if you hadn’t spent five or six years falling down drunk on a mixture of Ripple and blackberry brandy? How could you enjoy driving a Lotus 7 if you’d never owned a ’51 Buick Straight Eight with the hydraulic lever shocks worn out? (Conversely, how could you remember the ’51 Buick fondly if you’d never shaken your fillings loose in a Lotus 7?) How could you appreciate women if you’d never seen the blind date I took to the Wisconsin State Fair? Why would you pay $25 for a Rolling Stones concert ticket if you’d never heard Barry Manilow? How could you ever vote for Reagan if you’d never seen Carter? Or Carter if you’d never seen Nixon, or Nixon without Johnson to drive you to the polls?

You couldn’t!

Parallels and examples were everywhere, but owning and riding 50s and 90s and 160s was all tied up with paying your dues, coming up through the ranks, earning your wings and all the other names for the same thing. If privation and long-suffering patience really built character, as parents and Marine Corps recruiters always told us they did, then those of us who owned 50s would have gone around looking like a cross between Dr. Albert Schweitzer and the Prisoner of Chillon. At the age of 16.

Luckily the Dorian Gray principle is largely overrated—some of the most corrupt people I know look remarkably young and healthy—and in most cases there seems to have been no harmful character alteration or other permanent damage from riding these small bikes. If anything, the reverse is more likely true. It just may be, to paraphrase Orson Wells on wine, that enthusiasts benefit if they ride no motorcycles before their time. Q

View Full Issue

View Full Issue