RIDING FAST

ROADCRAFT Part 1

Going Fast in Control Means Riding Smoothly. The Secret Is Knowing What Smoothness Is.

Steve Kimball

The perfect corner, explains road racer Ron Pierce, is when you come into the corner using all the brakes the bike has, you feel the forks flexing back and forth under braking pressure, and you smoothly release the front brake as you lean the bike over more and more until the front brake is off and the front tire is beginning to slip at the apex of the turn. Then you get on the gas, still holding on a little rear brake to control wheelspin, and use a big burst of power to kick the back end out and straighten the bike, keeping the front end from sliding as you power out of a corner with the rear brake keeping the rear tire from going up in smoke.

Nothing is wasted in the perfect corner. All the braking power available is used. The engine is developing maximum horsepower as the bike exits. At all times the tires are at the very limits of adhesion, first because of the tremendous force of the brakes, then with the combination of braking and turning, then just turning, and finally with the transition from turning to accelerating.

Making a perfect corner is unusual even for a racer of Pierce’s considerable and demonstrated talent. But Pierce has experienced the thrill of the perfect corner enough so that he can describe it and so that he knows not just what that perfect corner is, but how to work at his own riding skills so that he might make more perfect corners.

In a dozen years of successful road racing Pierce has learned an incredible amount about not just how to go fast, but how to learn to go fast, how to set up a motorcycle for going fast, and how to survive. All of that made him valuable to racing teams for racing and testing. Pierce has other skills that make his knowledge valuable to other motorcyclists. He has a great insight into what enables riders to go fast and he is articulate in explaining that knowledge.

Spending a day talking with Pierce about riding motorcycles at the limit is informative and exciting. The level of competition Pierce experienced has made some of his observations seem out of touch^ with every-day highway riding until one thinks of the race situation: when knowing how to make a perfect corner is the only way to avoid an accident.

Yet there’s a basic and important difference in how Pierce rides fast and how the average fast rider goes fast. It has to. do with the various limits of the motorcycle and which ones can be pushed the farthest.

To most motorcyclists the way to go faster is to get more horsepower. Watch a street rider go fast and you’ll usually see some heavy-duty throttle twisting. He’ll race his motor and ride his chassis.

That’s just the opposite of Pierce’s rac-^ ing technique. A racing engine is a relatively known quantity, says Pierce. A good tuner can tell a racer how long an engine can last depending on how hard it’s run. He might be able to say that his engine can run a 200 mi. race if it’s not revved over 10,500 rpm, but if it is revved much beyond 10,500 the engine won’t last. -When a tuner has worked with an engine enough, the racer might get even more advice on the life of the engine, getting one figure for a normal redline, a higher figure for occasional use and an absolute maximum for the last lap.

Given a limit on engine revs, Pierce would ride within the engine’s limits, shifting at redline, using the clutch for shifts, and he would race the chassis, pushing the machine harder and harder in corners, using the brakes later and later, trying for that perfect corner and the fastest transitions.

Some club racers, says Pierce, are successful in the short club races where they can ride an engine harder and still finish a nine lap race. But the same racers can’t use the same techniques in a long professional race and have the engine survive.

What makes a racer fast is what’s called smoothness. Yet that word, as simple as it sounds, does not explain what smoothness is or what a smooth rider does. Hundreds of articles have been written about various levels of racing, the author explaining that it’s some nebulous thing called “smoothness” that makes one racer faster than another. Yet anyone who has watched a really fast racer, no matter what the kind of race, knows that the word smoothness is 'misleading.

Smoothness may imply gentle sweeping motions back and forth and in and out of corners. And the beginning racer may avoid harsh movements so he can ride smoothly around the track. But that’s not smoothness. Smoothness is not gentleness. Smoothness is not slow. And a rider who is getting absolutely everything out of his bike looks almost violent as he wrestles the machine through corners, blasts away from corners and pounds into corners.

Defined properly, smoothness is a very narrow and very specific skill. Smoothness is using all of the motorcycle. Smoothness means there is no wasted traction during transitions. To a racer like Pierce or anyone else riding as fast and as hard as Pierce races, smoothness means throwing the motorcycle into a corner and backing off on the brakes at exactly the same rate so that there is no more braking or turning or acceleration than the tire can withstand before breaking loose. Smoothness is what keeps the motorcycle from crashing when it’s going at the absolute limits. But until a motorcycle is ridden near the limit, it’s not being ridden smoothly, it’s being ridden slowly.

Races are won or lost in the transitions between braking and turning and acceleration. Acceleration, by itself, is a simple action. It’s a matter of holding the throttle open and shifting at the redline without wasting time. Braking is more difficult and requires more experience so that maximum deceleration is achieved. And cornering, the matter of holding the motorcycle at the maximum angle of lean with the maximum weight transfer while keeping the motorcycle on a line that gives the greatest arc through the corner, even that is not difficult to understand, though it requires much skill to do. Putting those very different skills together, blending braking into turning and turning into acceleration does not involve an addition of difficulty, but the very multiplication of difficulty.

The key to transitions, or to smoothness for that matter, is knowing exactly how fast any controls can be moved. In braking the lever can be pulled in so hard and fast that the wheel locks, or it can be pulled in slowly or not hard enough and all the braking power won’t be used. In between these two possibilities is one absolute, exact amount of lever pressure and speed of application that provides the maximum braking without a loss of control.

How fast a rider can change what he’s doing determines how fast he can go around a racetrack. Calling such sudden movements smoothness only makes sense to the rider who’s raced at the edge. To the rider who has turned too suddenly, or accelerated too fast or braked too hard, the concept of smoothness—and that’s what it is, a concept—is very important. That’s why there’s been so much written and discussed about this nebulous thing called smoothness.

That it doesn’t look like what it is, is not important. The word, the concept, exists for the rider, not the spectator.

Much of what goes on in riding a motorcycle fast around a racetrack looks much different than what a rider actually does. Even a simple thing like sitting on a motorcycle is not what it appears.

Riding along on a racetrack behind Pierce on another bike demonstrates what a subtle difference there is between sitting and the perch assumed by a racer. From the sides of a track his movements on the bike are small, leaning into corners apparently sliding his butt off the saddle. It looks simple enough. But try sliding around at the same points that Pierce does and your leathers stick to the motorcycle’s seat and then let go all at once. At the same time the bike changes its angle of lean and the relative position of all the> controls changes. The combination of upsetting the balance of the bike, reorienting oneself to the controls and holding onto the handlebars and steering the machine from a new position don’t do anything to improve handling unless done properly.

Motorcycling is a sport of machines ... and of men. The machines improve by quantum jumps every model year. They are quicker and faster, stop shorter and steer straighter and track through curves more accurately than earlier generations could believe.

The other half of the equation isn’t so fortunate. We human beings have been basically unchanged for something like 100,000 years. We’re smart and possess a good sense of balance and position and have evolved a remarkable dexterity. Some of us can do incredible things with motorcycles and some of us can ride for millions of miles and scores of years and never suffer so much as a scratch.

Others of us aren’t that skilled or practiced or fortunate. We have the enthusiasm but lack the information that would enable us to become better, faster, smoother and safer riders.

We call this knowledge roadcraft. We see it as a distillation of disciplines; racing, touring, coping with city streets. There’s more to it than just going fast or surviving. Roadcraft is, in a sense, an art.

Roadcraft is also a mass of detail, so much so that it’s being presented as a series.

Part One comes from the track, with the help of Ron Pierce. He needs little introduction to racing fans, as he’s ridden for BMW and Honda, won the Superbike class at Daytona, finished second in the 200 and done well against the world’s best in endurance races as well as sprints.

He also knows how to make the machine work for the man ...

To make the most of hanging off, Pierce doesn’t actually sit on a motorcycle. He crouches on it. His weight is supported by his feet, which are carefully positioned on the footpegs. The feet aren’t positioned so that he has ready access to the brake and shift levers, but are positioned so that he has the movement on the motorcycle. When he shifts or brakes with his foot, that foot must be shifted forward to operate the shift lever or brake pedal. By resting most of his weight on the balls of his feet, he is free to move from side to side without upsetting the balance of the bike.

His movement on the motorcycle, while usually explained by increasing weight transfer to the inside of a corner, has a more important function. It maintains his position relative to the ground.

“When I first started racing someone told me that people who lean their heads crash,” said Pierce. “Look at pictures of great roadracers and all of them have their heads level with the horizon. That’s for balance. It’s harder to maintain balance with your head leaned over with the motorcycle.”

So Pierce doesn’t just climb around on a motorcycle, he allows a motorcycle to move around under him, leaning over to the greatest angle of lean while he slides off to the inside of a corner, his eyes level with the horizon and even his upper body relatively upright because his butt has shifted clear off the saddle.

This weight shift, when viewed from directly behind Pierce, is extreme. Viewed from the side there is little weight shift. Pierce doesn’t want to slide back and forth on the motorcycle because that affects weight transfer too, only not in a constructive manner. Lateral weight transfer is what makes a motorcycle go around a corner and the more weight transferred, the faster the motorcycle can go around. Fore and aft weight transfer also helps a motorcycle do its job as long as it’s controlled. So the bike is tuned to provide optimal weight transfer back for acceleration and forward for braking, but it’s the chassis that controls this, not the rider.

A motorcycle’s size is important to the rider and how much he must hang off, according to Pierce. On a 550 lb. box stock motorcycle a 150 lb. rider becomes a much smaller percentage of the total weight than the same rider on a 200 lb. lightweight. Also, larger motorcycles are generally wider and have more limited angles of lean before the engines scrape on the pavement. The smaller bikes simply run out of tire.

“The Superbikes are probably the easiest bikes to ride I’ve ever ridden,” said Pierce. “It’s easier to ride a big bike because it has more power. It’s more forgiving with extra power to get you out of trouble. They can really hurt you, too. They’re heavy and hard to get under control when you do lose control. It’s the mass of a big bike that gets you in trouble. It’s slow coming on and slow coming off.

“For a beginner, lightweights are better because they help you develop the feel and control.” Bikes with larger motors, says Pierce, rely on torque and broad power bands, while the smaller bikes pick up their peak horsepower in a narrower rpm range, making it more important to ride the smaller bikes smoothly.

Like most other successful roadracers Pierce started out riding smaller motorcycles. Small dirt motorcycles. This is not an unusual background for a first rate road racer. Kenny Roberts, Randy Mamola and Freddie Spencer were all dirt racers who roadraced too.

Racers who have competed on miles and half miles and TT tracks have learned different skills than the strictly pavement racers. That’s one of the reasons Roberts has been so successful as a roadracer. He’s learned to control a motorcycle while it’s sliding. The other dirt racers-turned roadracers have developed some of the same skills and to much the same effect.

Just how did Pierce learn to control a motorcycle when the tires were at the edge of traction? It’s not an innate skill. “I don’t believe there are any naturally great racers,” he says. “Some get more proficient at it than others by practicing and working at it and some learn better than others, but no one knows how to control a slide at 100 mph without trying a slide.”

Learning how to slide a motorcycle at 100 mph isn’t a simple matter of riding a motorcycle until it falls down. What Pierce did to develop the skills was to practice at very low speeds on a local gokart track. He went out with a motorcycle and rode around the tiny, tight kart track learning to lean the motorcycle over as far as it would go and discovering what happened when he leaned too far and what happened when he used too much brake or not enough.

The skills he learned at 20 mph are the same skills Pierce uses at 120 mph. “Instead of practicing a front end washout at 100 mph, if you practice that at 5 mph you’ll learn how to control it so that if it happens at high speed you can probably save it.”

Practicing control at the limits is what builds proficiency, according to Pierce. He feels it’s the amount of practice that determines the amount of proficiency. That’s why, he says, Kenny Roberts knows more about tires than any other racer: Roberts has done more tire testing than any other racer.

Practice is not a haphazard time spent riding a motorcycle. Pierce plans his practice and learns a motorcycle and a track by following his plan. When learning a new track he doesn’t just go out and ride around the track as fast as he can. The only way to really learn a track, Pierce says, is to work on one part at a time. Beginning at the first corner, Pierce works on just that one corner, trying different braking points, different entry points, different apexes. Besides knowing the fast line through a corner, Pierce wants to know every line possible through the corner so that if there’s some oil on the line, or a slower bike, he knows where he can ride around the problem with the least problem.

After mastering one corner, learning every way through it and just how fast he can go into and out of that corner, Pierce moves on to the next corner and goes through the whole procedure again.

When all the corners are practiced separately they can be tied together and the entire course practiced. But the learning “isn’t over. Like any good street rider, Pierce has discovered various problems that can occur during a race. It could be a mechanical problem with the motorcycle, or a problem with traffic. “Rather than always try to avoid problems, it’s better to predict any problem that can occur and Hearn how to handle it,” says Pierce.

That’s the way Pierce sets up a bike, also. “You go out and ride it. Find out its faults. It’ll be rough and soft, the forks will flex and the brakes will fade. Then you start working on basics. Handling and wheels and stuff. With the Honda Supervbike the first thing we changed was the forks. They flexed way too much. And the brakes.

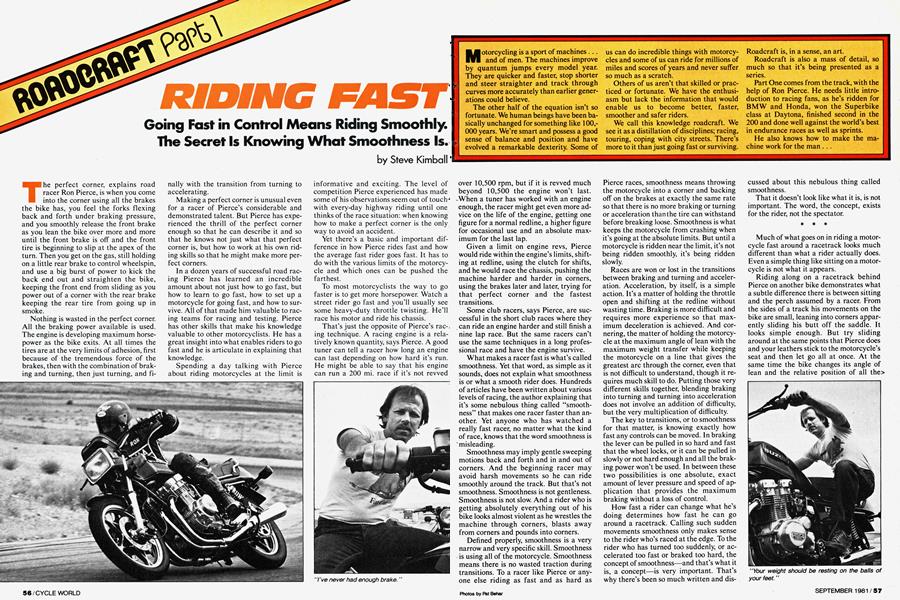

“I’ve never had enough brakes.” Enough brakes for Pierce means he can virtually stand it on end, controllably, repeatably, lap after lap, corner after corner, ^using the same amount of lever pressure at the same braking point.

Pierce is sensitive to a motorcycle’s weaknesses on a race track. When the Honda Superbike was first tested Pierce went out and rode it, came back and told the engineers that the forks flexed. To Pierce the matter was simple. When he pulled the brake lever hard he could feel the flex through his fingers. At some points around the track, he says, he could look down and watch the forks bend back as he grabbed a handful of brake. The forks were fixed. And this year Honda’s 750 and 900F models have bigger fork tubes.

Fixing one deficiency on a bike doesn’t Always work as it’s supposed to. Sometimes eliminating one problem eliminates other problems that don’t appear to be related, and sometimes it causes new problems. It all intertwines, says Pierce.

That’s why using racing slicks on a street bike isn’t necessarily a good idea. The sticky tires can add loads into the frame and suspension that a stock bike isn’t designed to handle. That’s also why Pierce says a racebike can be harder for a novice rider to master. The racebike is designed to go fast at all times. Most important are the tires, which are chosen to operate within a narrow temperature range. Slow tires, for instance, are formulated to heat up slowly so they reach their designed operating temperature after several laps. Other tires are designed to heat up fast and they wear out faster. Street tires are generally designed to work well at lower temperatures, while providing better traction on surfaces occasionally covered with water, sand, or dirt. They are also designed to operate within the limits of cornering angle that street bikes can generate. That’s why Pierce doesn’t mind the scraping pegs on the street bike he rides. They warn him when the bike has used up the safe clearance and when the tires are near their limits.

If there is a clue to riding fast, it’s knowing the limits of the motorcycle and the rider. That’s the skill that makes for fast racers or for safe street riders.

Knowing the limits is a vital part of the racer’s most important asset: his attitude. Roadracing, says Pierce, is a mental activity. It requires concentration and confidence. The confidence comes from mastering the control of the motorcycle, but it’s still part of the racer’s battleground.

“When racing at LeMans one year on the endurance racer I was going down the straight at about 150, at night, over a hump when the right handlebar broke off just before the hairpin corner at the end of the straight. Now that kind of stuff can

detune you,” said Pierce. “That shouldn’t be on a racer’s mind. You can’t maintain total concentration if you’re worrying about having a handlebar fall off.

“Don’t worry about the other guys. You get confidence from checking out your motorcycle. Know your bike. You have to be confident in yourself and your mechanic.

“You can maintain concentration by being relaxed, not by being tense. You must be comfortable on the bike to concentrate.” And there are tricks. At the Onatrio Six Hour one year the Honda team had asked for a special compound tire that would be the best combination of traction and wear for the race. Goodyear made 25 of the tires and the Honda team bought all 25, immediately making sure everybody else knew they had all the good tires.

And in endurance races Pierce likes to have a pit board displayed every lap. “It’s somebody talking to me, helping me concentrate. It keeps me thinking about the race.”

The skills that create proficiency can be described without much difficulty, but they can’t be learned by reading a story or even watching someone demonstrate. The important skills, the braking and acceleration and steering can only be learned by trying. The value in talking with an exceptional racer or watching him demonstrate his riding is in discovering just how far out those limits are.

Learning those limits is not in itself a safe thing to do. Even the best racers crash in practice. But done right, practice in a safe environment is what builds the skills to make riding safer in an unsafe environment.

And that’s where we all ride. E9

View Full Issue

View Full Issue