Honda's High-Tech Tracker

Juggling The Fast vs Last Equation

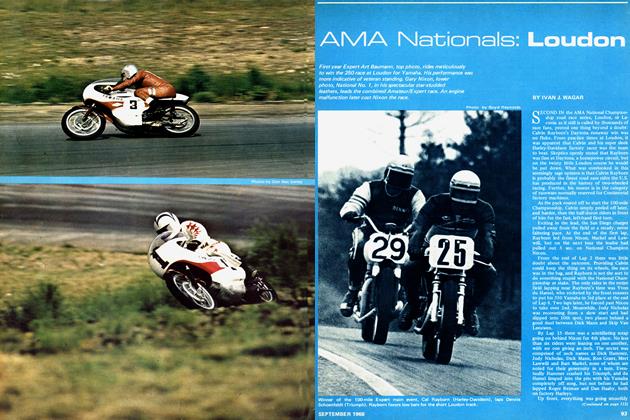

Honda’s plans to compete for the national championship have been an open secret for nearly a year. Team Honda already had a Formula One bike for road racing, CR250-derived short track and XR500-based TT machines. They did some testing late in 1980 with a chain-drive CX500 engine in a flat track chassis.

The real thing, formal name NS750, appeared in April, running the half-mile at Ascot and the mile AMA national at Sacramento. The NS750 didn’t win. It didn’t even make the main event. Team Honda went home happy anyway, because the bike sounded right, finished intact and showed the fans Honda cares about Winston Pro racing.

The note here, one race into the program, must be one of cautious optimism, blended with appreciation for Honda’s willingness to invest in Winston Pro, and for Honda’s inventiveness in turning—literally—a touring motorcycle into a flat track racer.

Begin with the AMA’s rules. Unlike every other form of racing anywhere in the world, AMA national racing doesn’t allow boring and stroking to meet the displacement limit. You, okay, Honda, can’t get a 750cc Twin just by enlarging a 500cc Twin. If it’s built as a 500, it must run the 750 class as a 500.

The escape clause is that for AMA, production means at least 25 examples of the engine have been built and will be offered for sale. Honda took the obvious option: for marketing reasons, a racing production engine should be at least based on a real production engine. Honda gave the CX500 a new crank, stroked to 63 mm from 52 mm. The block got two sleeves, shaped like upside-down top hats to raise the cylinders on the cases, and to enlarge the bore from 78mm to 87 mm. Presto, a 749cc CX500.

Shaft drive became chain drive by removing the back of the transmission, fitting a countershaft sprocket and casting a new, uh, side cover for what used to be the back of the engine, with allowance for a bigger flywheel and the new output shaft next to the flywheel. Because the countershaft sprocket had to be turning in the same direction as the crank, at the engine’s new left rear, the engine itself was turned one quarter-turn to the right, so the transverse V-Twin is now fore-and-aft.

The CX500’s heads are skewed 22° from the crankshaft’s plane, so the road bike has its carbs away from the rider’s knees and the exhausts splayed outboard. This gets crowded with the cylinders in line, so the former exhaust ports are now intakes, on the NS750’s right with carbs—Lectrons or Dell’Ortos—pointed out, and the former intakes are exhausts, on the bike’s left with the pipes routed forward, beneath the engine into megaphones on the right. Milers only turn left, so there’s no clearance problem. The fourvalve heads still use pushrods from a camshaft in the vee, although naturally the cam timing and ports have been reworked, and the NS is water cooled, by two radiators the first time out and three—they were worried about mud plugging the fins—for the second race.

Frame and suspension were done by American tuner Jerry Griffiths, with help and parts from the Honda factory. The chassis is conventional; full cradle frame, telescopic forks, aluminum swing arm with one Works Performance Shock on each side. It’s the widest swing arm ever seen, because the outboard countershaft needed a wide hub and the shocks had to clear the chain.

Front suspension work is still in pro> gress. There were two NS750s at the Ascot half-mile. One had leading-axle forks from the XR200, with a clever set of adjustable triple clamps so Griffith could experiment with rake and trail. For Sacramento, both bikes wore straight-leg Marzocchis, just like most of the other milers. Either the team got the answers they were after, or they’re working on other areas higher on the priority list.

Specifications are on the brief side, and subject to change without notice. Wheelbase can vary between 52.5 and 55 in., with both Spencer and Haney using 54 in. at Sacramento. The Marzocchis have 26° rake, 3 in. trail. An educated guess (our lips are sealed) puts dry weight of an NS750 at 285 lb. A race-ready Harley XR750 weighs 320 or so, the next-newcomer Yamaha 750 is targeted at 300 lb. Dyno tests show the NS750 to have 85 bhp with a working redline of 9200. A well-tuned Harley will have at least as much power, at lower revs, but the XR engine is 10 years old so the Honda engine surely can be tuned to the Harley’s equal.

How does the NS750 work? With practice, you can hear the difference in exhaust note, with the Honda being spun faster and having a higher pitch, but the difference between a 45° Vee and an 80° Vee isn’t as distinct as we expected.

More useful here is the Honda philosophy. In every other form of racing, Honda has always gone for power through rpm. At Sacramento, despite the monstrous 3in. rim and fat rear tire, the NS didn’t have the traction to put its power on the ground, so Honda R&D may have the assignment of getting mid-range punch and maximum power.

Early days, as they say. From trackside the Honda is the darnedest looking collection of lumps and bulges and radiators ano pipes ever seen at a dirt track. Never has the XR750 looked so sleek, so trim and tidy. Nor have we even seen the Yamaha 750, scheduled for its first race before this appears in print.

Team Honda has work to do. Meanwhile, racing fans and techno-freaks have something really different to watch.