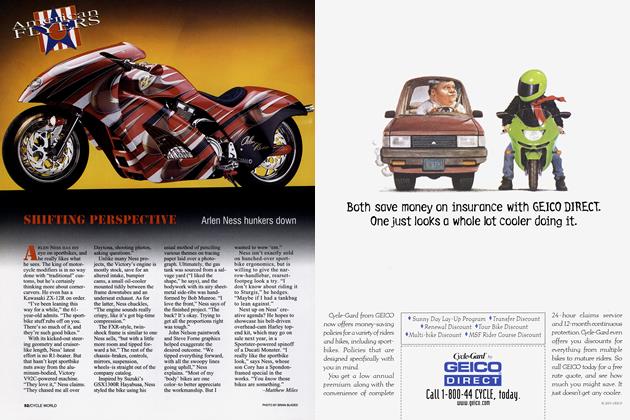

SUCCESS FOR PROJECT HAWK

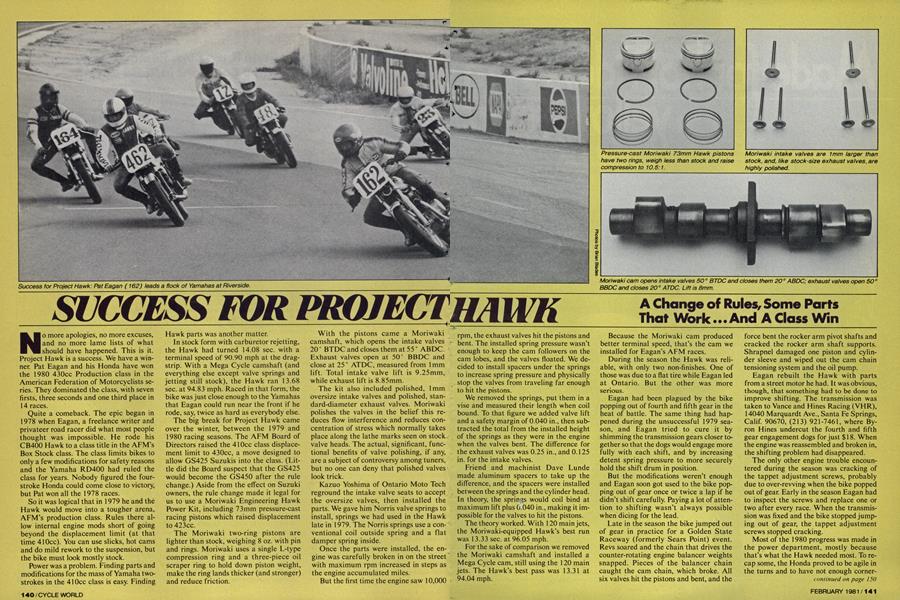

No more apologies, no more excuses, and no more lame lists of what should have happened. This is it. Project Hawk is a success. We have a winner. Pat Eagan and his Honda have won the 1980 430cc Production class in the American Federation of Motorcyclists series. They dominated the class, with seven firsts, three seconds and one third place in 14 races.

Quite a comeback. The epic began in 1978 when Eagan, a freelance writer and privateer road racer did what most people thought was impossible. He rode his CB400 Hawk to a class title in the AFM’s Box Stock class. The class limits bikes to only a few modifications for safety reasons and the Yamaha RD400 had ruled the class for years. Nobody figured the fourstroke Honda could come close to victory, but Pat won all the 1978 races.

So it was logical that in 1979 he and the Hawk would move into a tougher arena, AFM’s production class. Rules there allow internal engine mods short of going beyond the displacement limit (at that time 410cc). You can use slicks, hot cams and do mild rework to the suspension, but the bike must look mostly stock.

Power was a problem. Finding parts and modifications for the mass of Yamaha twostrokes in the 410cc class is easy. Finding Hawk parts was another matter.

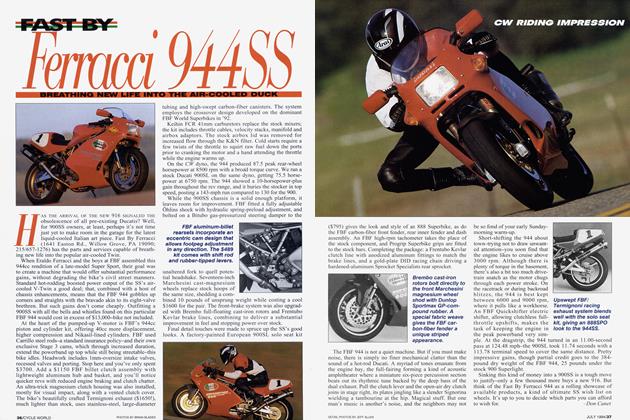

In stock form with carburetor rejetting, the Hawk had turned 14.08 sec. with a terminal speed of 90.90 mph at the dragstrip. With a Mega Cycle camshaft (and everything else except valve springs and jetting still stock), the Hawk ran 13.68 sec. at 94.83 mph. Raced in that form, the bike was just close enough to the Yamahas that Eagan could run near the front if he rode, say, twice as hard as everybody else.

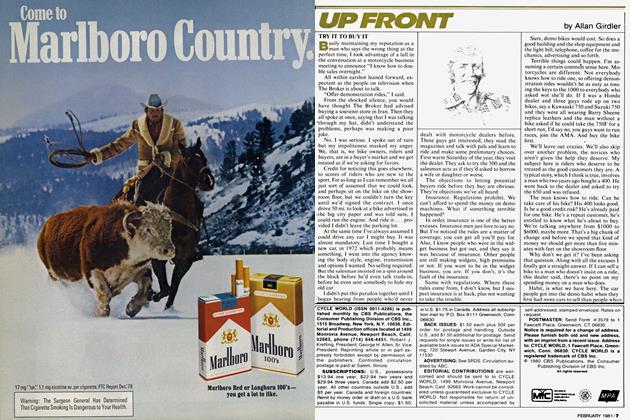

The big break for Project Hawk came over the winter, between the 1979 and 1980 racing seasons. The AFM Board of Directors raised the 410cc class displacement limit to 430cc, a move designed to allow GS425 Suzukis into the class. (Little did the Board suspect that the GS425 would become the GS450 after the rule change.) Aside from the effect on Suzuki owners, the rule change made it legal for us to use a Moriwaki Engineering Hawk Power Kit, including 73mm pressure-cast racing pistons which raised displacement to 423cc.

The Moriwaki two-ring pistons are lighter than stock, weighing 8 oz. with pin and rings. Moriwaki uses a single L-type compression ring and a three-piece oil scraper ring to hold down piston weight, make the ring lands thicker (and stronger) and reduce friction.

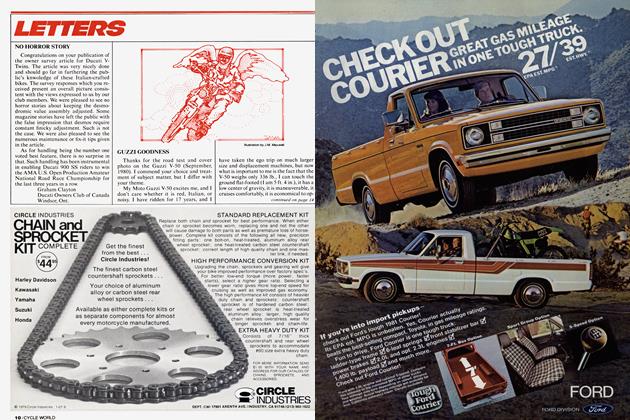

With the pistons came a Moriwaki camshaft, which opens the intake valves 20 ° BTDC and closes them at 55 ° ABDC. Exhaust valves open at 50° BBDC and close at 25° ATDC, measured from 1mm lift. Total intake valve lift is 9.25mm, while exhaust lift is 8.85mm.

The kit also included polished, 1mm oversize intake valves and polished, standard-diameter exhaust valves. Moriwaki polishes the valves in the belief this reduces flow interference and reduces concentration of stress which normally takes place along the lathe marks seen on stock valve heads. The actual, significant, functional benefits of valve polishing, if any, are a subject of controversy among tuners, but no one can deny that polished valves look trick.

Kazuo Yoshima of Ontario Moto Tech reground the intake valve seats to accept the oversize valves, then installed the parts. We gave him Norris valve springs to install, springs we had used in the Hawk late in 1979. The Norris springs use a conventional coil outside spring and a flat damper spring inside.

Once the parts were installed, the engine was carefully broken in on the street with maximum rpm increased in steps as the engine accumulated miles.

But the first time the engine saw 10,000 rpm, the exhaust valves hit the pistons and bent. The installed spring pressure wasn't enough to keep the cam followers on the cam lobes, and the valves floated. We de cided to install spacers under the springs to increase spring pressure and physically stop the valves from traveling far enough to hit the pistons.

A Change of Rules, Some PartS That Work...And A Class Win

Brian Blades

We removed the springs, put them in a vise and measured their length when coil bound. To that figure we added valve lift and a safety margin of 0.040 in., then sub tracted the total from the installed height of the springs as they were in the engine when the valves bent. The difference for the exhaust valves was 0.25 in., and 0.125 in. for the intake valves.

Friend and machinist Dave Lunde made aluminum spacers to take up the difference, and the spacers were installed between the springs and the cylinder head. In theory, the springs would coil bind at maximum lift plus 0.040 in., making it im possible for the valves to hit the pistons. The theory worked. With 120 main jets, the Moriwaki-equipped Hawk's best run was 13.33 sec. at 96.05 mph.

For the sake of comparison we removed the Moriwaki camshaft and installed a Mega Cycle cam, still using the 120 main jets. The Hawk's best pass was 13.31 at 94.04 mph.

Because the Moriwaki cam produced better terminal speed, that's the cam we installed for Eagan's AFM races. During the season the Hawk was reli able, with only two non-finishes. One of those was due to a flat tire while Eagan led at Ontario. But the other was more serious.

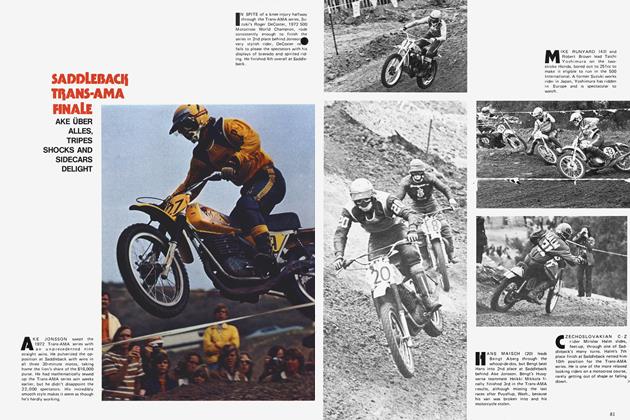

Eagan had been plagued by the bike popping out of fourth and fifth gear in the heat of battle. The same thing had hap pened during the unsuccessful 1979 sea son, and Eagan tried to cure it by shimming the transmission gears closer to gether so that the dogs would engage more fully with each shift, and by increasing detent spring pressure to more securely hold the shift drum in position.

But the modifications weren't enough and Eagan soon got used to the bike pop ping out of gear once or twice a lap if he didn't shift carefully. Paying a lot of atten tion to shifting wasn't always possible when dicing for the lead.

Late in the season the bike jumped out of gear in practice for a Golden State Raceway (formerly Sears Point) event. Revs soared and the chain that drives the counter-rotating engine balancer weights snapped. Pieces of the balancer chain caught the cam chain, which broke. All six valves hit the pistons and bent, and the

force bent the rocker arm pivot shafts and cracked the rocker arm shaft supports. Shrapnel damaged one piston and cylin der sleeve and wiped out the cam chain tensioning system and the oil pump.

Eagan rebuilt the Hawk with parts from a street motor he had. It was obvious, though, that something had to be done to improve shifting. The transmission was taken to Vance and Hines Racing (VHR), 14040 Marquardt Ave., Santa Fe Springs, Calif. 90670, (213) 921-7461, where By ron Hines undercut the fourth and fifth gear engagement dogs for just $18. When the engine was reassembled and broken in, the shifting problem had disappeared.

The only other engine trouble encoun tered during the season was cracking of the tappet adjustment screws, probably due to over-revving when the bike popped out of gear. Early in the season Eagan had to inspect the screws and replace one or two after every race. When the transmis sion was fixed and the bike stopped jump ing out of gear, the tappet adjustment screws stopped cracking.

Most of the 1980 progress was made in the power department, mostly because that's what the Hawk needed most. To re cap some, the Honda proved to be agile in the turns and to have not enough cornering clearance. The exhaust and pegs ground before the slicks are fully used. Again, the Yamahas have benefited from' years as club racers—the last RD400s,, the Daytona models, in fact have their pipes and pegs tucked in at the factory. The production rules allow relocation of the stock exhaust.

continued on page 150

continued Jronz page 141

If that can be done. Most bikes, no problem. But the Hawk has an ekpansiorf box at bottom dead center of the machine. It can’t be raised or moved and it’s thew part that hits.

So cornering clearance was gained by raising the entire bike. We used longer damper rods in front and S&W shocks, one inch longer than stock, in back. Th» forks work fine; we even left the damping rates alone. The shocks are only fair. They" weren’t designed for racing and because S&Ws can’t be rebuilt, they can’t have their internals changed. We did swap springs, but that was as far as we could go.

The bike began life as a 1979 Hawk* Type II, the one with the disc front brake, which we wanted, and electric start, which added 30 lb. and which we didn’t need, but the rules don’t allow you to change brake type, so we kept the electrics to get the disc. A good choice. With Ferodo pads, the Hawk will stop as quickly and with as much control as any machine in the class. ^

To save weight we switched to wire spoke wheels, relaced with 8-gaugespokes. Rims are wider, from WM2 to WM3 in front, WM4 in the rear. For rain and street use—gotta break the engine in, and sometimes ride to work—the tires were Dunlop K81 Mklls, and the best slicks we used were Goodyear, a 3.25-19 D1949 front, 3.50-18 D1934 rear.

Project Hawk still isn’t the fastest machine in its class. Eagan’s riding—he was fifth in Superbikes at Daytona 1980—has a lot to do with the victory. What the Hawk is now is a club racer, good enough to win or at least compete on the club4 level. Plug the lights back in, attach the stands and mirrors, use street-legal tires and the Hawk is still a useful road machine.

Moriwaki now has a U.S. distributor; Ontario Motor Tech. Corp., 6850 Vineland Ave. #16, N. Hollywood, Califs 91605. Retail price of the piston kit, with rings, circlips and head gasket, is $125. The cam costs $115. Oversize and polished intake valves are $25 each—you’ll need four, don’t forget—and polished exhaust valves are $27 each.

Last year at the end of the season we-< said we’d had fun, lost some skin off knuckles and learned a lot. At the end of this season, we’ll reverse the football coach. Winning isn’t the only thing, but it sure beats losing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue