"I Figured I Had Everything covered"

How Kenny Roberts Didn't Win Another 500cc World Championship

John Ulrich

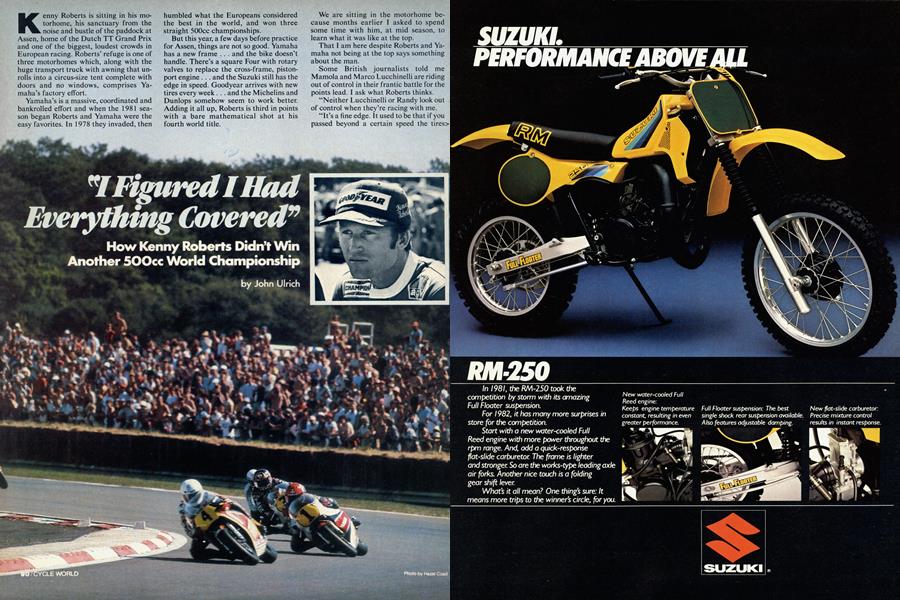

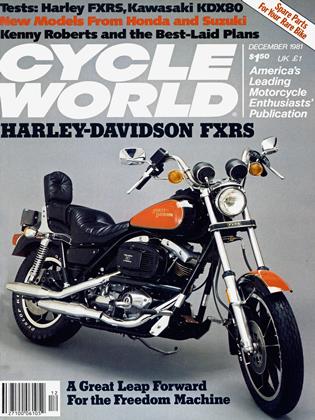

Kenny Roberts is sitting in his motorhome, his sanctuary from the noise and bustle of the paddock at Assen, home of the Dutch TT Grand Prix and one of the biggest, loudest crowds in European racing. Roberts’ refuge is one of three motorhomes which, along with the huge transport truck with awning that unrolls into a circus-size tent complete with doors and no windows, comprises Yamaha’s factory effort.

Yamaha’s is a massive, coordinated and bankrolled effort and when the 1981 season began Roberts and Yamaha were the easy favorites. In 1978 they invaded, then humbled what the Europeans considered the best in the world, and won three straight 500cc championships.

But this year, a few days before practice for Assen, things are not so good. Yamaha has a new frame . . . and the bike doesn’t handle. There’s a square Four with rotary valves to replace the cross-frame, pistonport engine . . . and the Suzuki still has the edge in speed. Goodyear arrives with new tires every week . . . and the Michelins and Dunlops somehow seem to work better. Adding it all up, Roberts is third in points with a bare mathematical shot at his fourth world title.

We are sitting in the motorhome because months earlier I asked to spend some time with him, at mid season, to learn what it was like at the top.

That I am here despite Roberts and Yamaha not being at the top says something about the man.

Some British journalists told me Mamola and Marco Lucchinelli are riding out of control in their frantic battle for the points lead. I ask what Roberts thinks.

“Neither Lucchinelli or Randy look out of control when they’re racing with me.

“It’s a fine edge. It used to be that if you passed beyond a certain speed the tires> would slide, and when the tires slid you fell down. Now the tires are better and you’ve got to slide to be in the hunt.

“In Yugoslavia I was sideways almost the whole race. I had to be, to keep up with them. I saw Randy get sideways once at that race, coming onto the main straight. He was going through flat out, on the tank. I was sitting up, nursing the throttle and keeping it in a drift because that’s all I could do.

“When I’ve raced with Randy this year he hasn’t even had to ride 95 percent. Suzukis outhandle us so badly that when I ride 110 percent, they can just follow around and watch me.

now we’re working with tire constructions that have a little more traction. Dunlop and Michelin both have forward traction on us, especially on circuits that are hard on tires. We’re getting that dialed in, I hope.”

Roberts’ eyes were wide open now, steely blue and unblinking, saying without words that he was concentrating on each word, studying the questions one by one.

“Suzuki is in a position where they don’t have to make any potentially disasterous decisions. They’ve had years with that bike, so they’ve got it pretty well wired.

“We make decisions when we don’t know if the changes will work or not. We’re running a bike that the factory just built. We have no test time on it. And before, when we had the time for testing, we had nothing to test. We get to the race and we don’t know if the tires will hook up, or if they’ll go the distance. We don’t know if the triple clamps will work, a lot of things.

“Turn it around, say our bike gets real good, as good as theirs or better, then they’ve got to make decisions they may not want to make.

“That’s what I need to happen.”

Roberts stared through the walls of the motorhome, far away.

“Turn it around,” he said, savoring the prospect. “Win two or three of them. Whether 1 can do it or not is a big if.”

I ask how long it took to build the new square Four.

“Boy, I don’t know. It was quick. All I know is I thought I was racing the old one until two weeks before Europe and then they told me I had a rotary valve.”

Where did the idea come from, Roberts or Yamaha?

“They did it. It’s just a known fact that rotary valves are a little better. They’re easier to make go faster. Yamaha’s put a lot of time and effort into the piston-port and it goes fast, for a piston-port. Winning the world championship three years in a row with the Suzukis being faster was pretty good.

“Our bike was a lot lighter. They were faster. Then they started lightening and they’ve gotten even quicker. Randy can sit up and go by me on the straights, just laugh at me. It got that bad.

“The Yamaha puts out more power than it did with piston ports. The new bike weighs more, not much but it does weigh more. At the beginning the engine location made it feel heavier than it was. Now that the chassis is fairly close, it doesn’t. Top speed isn’t much different but boy! all the way up!”

Inside his motor home, Randy Mamola waits for the race. “To ride a 500 is easy,” he says. “To race a 500 is hard. To ride around doing a lap time of 2 min., 55 sec. is so much easier than doing a lap in 2:52 that you just wouldn’t believe it. To ride around at three seconds slower is so much easier on you, so much easier on your body, your thinking, everything. Once you get your concentration and you’re thinking at every corner what’s coming up next, hew to be smooth and how to get there, how to get through it the quickest, everything starts falling together and all of a sudden you’re down to 2:52. I didn't even know I did a 2:52 when I did it. It just didn’t seem like it. You’re so heavy in concentration that you don’t even know it. And every once in a while, you get into a slide or something, something happens, say the tire locks up for some reason or something like that. That sort of out-of-control type thing where you’re in control because you’re concentrating so much and you just don’t goof up. It comes with experience. It took a long while to get used to. When I started it was like, here I am in the 500 class, the biggest class and then all of a sudden it’s just, like, to me, it’s just like any other old race, any dirt track race, anything else.

“The struggle to get to that point is so hard that once you get there you just get there. It’s not a big step up. You’re working so hard to get there. Last year I still sort of favored Kenny as a rider, as someone to beat. And this year, I feel that I’m equal to him as a rider and therefore I don’t look up to Kenny Roberts anymore. Not that I wanted to be Kenny Roberts or anything, just that he was number one and he was the rider, he was just the best. And now, all of a sudden I’m at that stage, and me and about four other riders have moved up this year. I think about it. I could be number one. I’m leading the points right now. Gee, that’s great, but as the season goes on, as each race goes on I don’t think about the next race. I think about the one I’m at, and right now I think about Assen. I don’t think about going to the next Grand Prix in Belgium.

“The main thing in 500 right now is the machine. On rider ability we’re all fairly equal. There’s one other big factor and that’s tires. The Dunlops I use have been working really, really well every single race. Kenny’s Goodyears just aren’t hooking up.

“Last year I didn't even get to see the bike until the first Grand Prix and by the time the second Grand Prix hit we had four or five different frames to choose

from, and it was too big a mixup. This year I tested the bike before the season began, and we got everything squared away and sent it back to Suzuki in Japan, made changes, brought it back out, and started out good from the beginning.

“I’ve been having some problems in practice,” continues Mamola, peeking out the the window of his motor home, then looking back. “I tried a new aluminum frame, which is a lot lighter than the steel one, but it rained in my practices and that kept me from riding it and getting some good testing on it. I’m going to have to ride the steel frame one. We’ve been having a little problem with it wobbling and they’re trying to get it fixed and we made a change after the final practice and I’m not sure if it’s going to work out.

“I’m going to go out there and see who’s going to be there. I’m sure that Marco (Lucchinelli) and Kenny are going to be right there, and if it ends up being a threeway battle I’d just as soon sit back with

them and see what happens. If I can’t hang onto them because the bike’s not handling good enough ... to me it’s the points. I gotta get as many points as I can. I know that there are other races and there’s no use in me crashing here. It’s a difficult track and if you make a mistake there’s no room.

“If I become World Champion I’m going to come back here again next year, see if I can hold onto it. I hope that if I do get to be World Champion that Suzuki won’t stop development because that’s just the way the factories work. Once they have something good, they leave it at that until they get beat, and that’s what Yamaha was doing to Kenny. Kenny was winning on his old bike and all of a sudden the Suzuki was getting better and better because Suzuki was number two and they wanted to be number one. And that’s how we surpassed them at the end of last season.”

continued on page 96

continued from page 93

Looking at Richard Schlachter’s rusting, peeling ’71 Ford Transit van—parked next to his dirt-floor tent in the Assen pits amidst American motorhomes, German buses and French semi-trailer trucks plastered with names of sponsors—is like spotting a one-room cabin with outhouse among the glittering casinos of the Las Vegas strip.

“People ask me where my spare bike is,” mused Schlachter as he gazed at the Dutch sky and wondered when the rain would start. “1 say 1 don’t have one and the reaction is as if Fd said my house didn’t have any plumbing.”

Next to the tent is a towering 60-ft. semi emblazoned with the name of a single sponsor. It contains a machine shop, parts room and fleet of motorcycles ridden by guys who never get into the top 10.

Anyone looking around would be hard put not to jump to the conclusion that Richard Schlachter, two-time U.S. Formula One Road Racing Champion, is wasting his time with his budget team.

And anyone walking through the paddock at Assen, or any other World Championship race—is likely to find the pits of factory and well-backed privateer teams to be tense, secretive places protected from outsiders by force fields generated by angry, threatening looks. Schlachter’s camp, without doubt the most modest in sight, is a warm and friendly place.

Which explains why, during my journey to record the losing struggle of Kenny Roberts and the upward career of Randy Mamola, when it’s time to relax it’s done in the company of Schlachter, mechanics Kevin Cameron and Donnie Dove, their lone TZ250H and the rusty van piled with spare engine, boxes of parts, tires, tools and suitcases.

Schlachter’s results have not been spectacular on paper. Before Assen his best finish was a fourth at Jarama, Spain. But the results sheets don’t tell the whole story. For one, GP races begin with dead engines; riders poised next to their machines, push-starting at the drop of the flag.

The technique is new to Schlachter and he hasn’t been able to master it despite intensive pre-start practice.

“I know I can run with these guys,” he says. “I’m at a disadvantage because of the starts. Working through traffic is so hard. Everybody’s going pretty fast and when you get up to a group of guys here, here and here” he gestures to indicate three riders filling the width of a corner, “to bust through is hard.

“Nobody back home knows what I’m doing over here. Not even the American riders. They read that Schlachter got a fourth at Jarama and they think ‘Why didn’t he win?’ Or they hear I qualified sixth somewhere and want to know what’s wrong. And I’m riding better than I ever have and going faster than I ever have.”

Why come to Europe?

“I got more satisfaction out of second place at Brands Hatch in the Transatlantic Series (on a TZ750) than I did being U.S. Road Racing Champion. I've learned so much and my riding has improved a great deal.

“Now I use my brain. It’s all in my head, what’s happening out there with the motorcycle, with me. It works out really well. I was over here for two and a half months straight at the beginning of the season. I’d race just about every weekend and I wasn’t burned out, not after two and a half months, because I was learning so much.”

“A racer in the U.S. is rather isolated because it’s a minority sport,” volunteers tuner Kevin Cameron. “Just everybody out in a field, riding around. It’s like gokarting—nobody there but the riders. It doesn’t make any difference. Nobody cares about us. It’s like water polo. Only the participants really care. Then you get to the German Grand Prix and see 120,000 spectators in the stands by 5 a.m. They’re not down-trodden or poverty-stricken. They’re well-off fans with $15 admission.

continued on page 100

continued from page 96

Then you think 'Why, this is a hell of a sport. This is something it might pay us to excel at.’

“There’s a whole bunch of good guys like Richard so if you make a little mistake, come out of a chicane a little bit wrong . . . five guys go past you.”

“Here in Europe you ride your eyes out and you get sixth,” Schlachter says. “If you slack off for a second you might be back in 12th, or 1 5th. Or not even qualify.

“Over here you’re riding with the best people in the world. It gives me a lot of incentive and satisfaction.”

Schlachter glances at the sky, filled with rolling gray clouds off the North Atlantic. “I try to get as many ideas as I can from other riders and by looking at the track and atmospheric conditions. I try to learn the track and go as fast as I can in that first practice session, especially on the last two laps of the first practice session when I’ve got some idea of where the track is going. Then if it rains nobody is going to beat my dry track time so I’m pretty sure that I’ll be in the first two or three rows on the grid.

“I’ll tell you,” adds Schlachter as a few drops of rain splatter against the tent, “the best thing I ever did was decide to race a 250 this year. Learning this track on a 250, a lot of corners are wide open. But on a 500

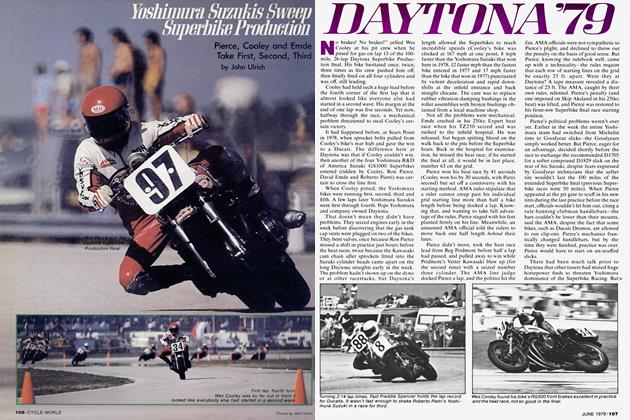

Race day. Schlachter has qualified sixth fastest in the 250cc race. “Dear God,” he says as he walks toward the pre-grid and looks up at the threatening skies, “don’t let it rain now.” Bob MacLean, a friend and U.S. sponsor who flew in to watch the race, carries rain tires toward pit row. Cameron wheels Schlachter’s bike and Donnie Dove carries tools and spare spark plugs.

Overhead 15 small airplanes circle lazily, pulling advertising banners and sometimes flying two or three deep in stacked formations. Campers and spectators line the circuit, 1 28,000 strong, cheering and yelling in a circus atmosphere. The weather is unpredictable, changing constantly, a few drops of rain, then dry, then a shower, then a monsoon, then sun in the span of a few hours. It’s been like that all week, but race day so far has only threatened rain, not delivered.

The riders make a warm-up lap, then assemble on the grid, engines quiet. A British journalist’s wife leans toward me from her vantage point atop the pit row

building and says “Richard’s in a superb position, second row with no one in front of him. If only he doesn’t make a hash of it— his starts are so often simply awful.”

Lor Richard Schlachter, all that matters now is watching the starter—and getting his bike to fire on cue. Around him the other men on the grid flex and tense their legs, clutches pulled in, first gear engaged,, breath held the microsecond before the flag drops. In less time it says to mouth the words “Oh, no!” the flag is down, most of the field is fired up and Schlachter is left" behind, pushing, pushing, pushing. Linally, even the official sweep car, which follows the field for one lap, accelerates out around him and heads down the start straightaway. It is an eternity before Schlachter’s and he aboard. But before he’s reached the top of first gear the bike spits back and ignites gasoline sprayed from the carburetors onto the engine during the long, befuddled push. A flash envelops his left leg with a POP! and he sits up, startled, looks at his leg too late to see the brief fire, and tucks in again, Schlachter passes the sweep car and is gone.

“Richard Schlachter is the man to watch,” booms the voice of English announcer Chris Carter, his words following the Dutch commentator and preceeding the German. “He had an atrocious start and is already carving his way through the pack.”

By the end of the second lap Schlachter is 1 8th; by the fourth lap, 1 3th. The places come more slowly now but after seven laps he’s 1 1 th. Two more times around and he’s

eighth, threatened by Martin Wimmer.

Wimmer rides for the West German Yamaha importer and has a TZ25QH like Schlachter’s.

Schlachter knew Yamaha’s racing department made a few special parts, like gears and ignitions and exhaust pipes. He couldn’t get them from Yamaha NV. Try Yamaha U.S., he was told. Telephone calls across the ocean got him nothing. Instead, he got to watch a Yamaha NV worker march up to Wimmer and hand over a bag of tricks.

Now Wimmer stalks Schlachter, using better drive off corners—gears and pipes?—to advantage. On the last lap the German gets past and secures eighth place.

Time for the 500 race. In the pre-grid area Randy Mamola laughs and jokes with Roberts, Graeme Crosby and Gregg Handsford, looking confident and relaxed. Nearby Dale Singleton is brooding, helmet on, eyes carrying the faraway stare of his raceface. Marco Lucchinelli walks through the paddock with helmet perched high on his head, backwards. He smiles and laughs. He has qualified fastest, 2:51.40. After trying a dozen tire combinations Roberts qualified second, 2:51.96. Mamola was third, 2:52.41, Crosby fourth at 2:53.55.

Singleton’s time, good for 26th on his private RG500 Suzuki, was 3:00.96. Earlier he told Schlachter you can’t hope to do well unless you have a factory bike. But sixth fastest, best privateer Boet van Dulman, rides a private, inline, piston-port Yamaha.

Minutes before the start the skies open and there’s a mad scramble to change from slicks. Van Duimen and Roberts choose rain tires. Lucchinelli picks rain, then at the last possible moment, intermediates. There’s a 10-min. delay, then the warm-up lap.

Roberts rolls to his position on the grid,> gesturing. Mechanics race out and swarm all over the bike. They work feverishly but in the end he drags the Yamaha off the track and watches the race leave without him.

One pad in the front brake was inserted backwards, exposing the aluminum backing to the rotor. On the warm-up lap bits of aluminum welded themselves to the rotor

and the front wheel locked nearly solid.

The timing is nearly tragic. Assen was the raced picked by Yamaha HQ for a visit by the executives. The man sent to assess Roberts’ effort instead found himself a referee. Roberts is sponsored by PJ-1. Yamaha has tested Bel-Ray. Roberts has nothing against Bel-Ray but likes to keep his word. Yamaha has nothing against PJ-1 but insists on using oil that’s been tested and PJ-1, along with tires and frames and suspensions, is one of the things there’s been no time to test.

In the end the PJ-1 stickers stay on Kenny’s leathers and helmet. The Bel-Ray stickers stay on the No. 1 Yamaha and Bel-Ray oil is in the bike. No big deal, just a contender for least-needed problem.

What lingers is the sight of that immobile Yamaha and rider, stuck on the line in front of live television, 1 28,000 fans and a grandstand packed with Yamaha personnel. One tiny mistake made hash of all those tires, the frame, the engine, those

three motorhomes and the giant truck.

Crosby led first, giving way to van Duimen with Lucchinelli, Ballington and Mamola close behind. Mamola crashed, running wide, across the painted limit line in a corner and losing it. Crosby crashed. Van Dulman had six seconds on Lucchinelli until the rain stopped—they don’t call him Lucky for nothing—and the factory Suzuki swept past to take the win and the points lead.

The race is still in progress. Roberts already changed into street clothes, paces angrily beside his motorhome. He doesn’t speak, just glares. An Italian film crew rushes up, takes one look at Roberts’ face and slowly edges away.

“The outside of my shield fogged up and I went into a fourth-gear corner,” said Mamola afterwards. “I didn’t go in too fast, I just went in on the wrong line and ran off the track. I couldn’t keep it on. It scared the hell out of me because I was sliding flat on my back and the bike shot straight up in the air, 10 ft. above me.

“Did you hear what happened to Kenny?” Mamola asks. “Not too good in front of all the Yamaha guys, eh?”

Lucchinelli is ecstatic. “I love rain,” he tells reporters. “I changed tires, rain to intermediates, on the line. I go fast in the rain.”

“Dad, how come you never do good here?” asks Kenny Roberts Jr. three hours after the disasterous race.

“Because the bike always breaks,” answers his father.

“It always breaks here?” wonders Kenny Jr.

“Yeah,” says Kenny Sr. “It’s only finished the race here once, so it’s a problem.”

“I don’t know why you even come here,” declares Kenny Jr., disappearing out the door of the motor home.

“I never figured it would turn out like this,” sighs Roberts after his son had gone. “I figured I had everything covered. I had the right tires.” He laughs and shakes his head. “We’ve had a special Assen compound for three years now and never got use to it.”

Roberts can see—in his mind if not his heart—the irony of this race. Unlike Schlachter, Roberts had a spare bike. There were two race bikes. One, the best machine, was fitted with 16-in. intermediate tires. The other had 18-in. rain tires.

“I was in here (the motorhome) with 1 5 min. to go. Kel came in and said ‘Sixteen inch?’ I said yeah.

“Then I looked outside and it was starting to rain. When I went out I told them to push the 18-in. bike up because it was really raining.

“Then I watched van Duimen. He knows this place better than anybody and he had rain tires, so I ran the rain tires. If I’d run the bike with the intermediates, which it turned out would have been the better choice, we wouldn’t have had the problem.”

Roberts sounds tired, resigned. He is quiet, not forceful and confident as he was before the race.

“You have this kind of year. This may be one of them.”

Two weeks later, Roberts’ chances of retaining his championship had vanished. He lost in Belgium, to Lucchinelli, on last lap when a lapped rider got in the In Italy, he ate in a restaurant the evening before the race and became violently with food poisoning in the early morning hours. When the race left the grid, erts was still in his motor home, dizzy, and hooked up to two intraveneous cose drips.

“The situation looks grim, doesn’t it?” asked Roberts.

“Well, that’s ... I guess that’s ... looks grim if you like . . . you know, you’re dead set on being the World Champion,” Roberts says slowly, pausing quently. “I’m not. I race motorcycles my business and if we can possibly win World Championship, we’re gonna that. But if we don’t, it’s not going to my heart. It just depends upon where you’re looking at it. It doesn’t mean ... doesn’t make any difference to me.”

Roberts does not sound convincing, even convinced.

“It’s business as usual every year,” continues. “If we win the World Championship it’s just a big bonus to us. I do business. I race motorcycles for Yamaha and if I do a 100 percent job, they’re happy. Because we’re developing a bike we’ve had some problems. I’ve racing for 10 years. I don’t jump up down and kick my feet if the bike breaks down. It’s just one of the things happens.”

Roberts pauses again, then continues. “It’s so intense in Europe that it wears out mentally quite a bit. Especially being on top. It’s tough.

“I’ve been one of the top guys in racing for 10, 11 years now. I’m thinking about retiring. It’s nothing new—I’ve often thought about it. But finding out when the best time to retire, that’s the tricky part. When is the best time to retire? Right now, I feel I’m still as competitive anybody out there. I think that when don’t feel that you’re competitive physically, that’s the time to get out of it.

“I could be competitive for five more years if I really wanted to work at it. don’t want to be competitive for five more years. That’s something you’ve got to vote your whole damn life to, every day, you’re gonna be competitive past age It’s just working at it. And I’ve worked it a long, long time. Since I was 14 (Roberts is 30 now) I’ve been doing nothing motorcycle racing.

“I have no desire to go into car racing go into anything. When I quit racing torcycles I’ll just quit.

“I haven’t seen anybody come up lately who is going to just blow everybody the weeds, me included. While you’re the position I’m in it’s hard to turn down everything you’ve worked for.

“Once I feel that with an equal bike not gonna win the World Championship, then I’ll probably retire.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

December 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1981 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

December 1981 -

Features

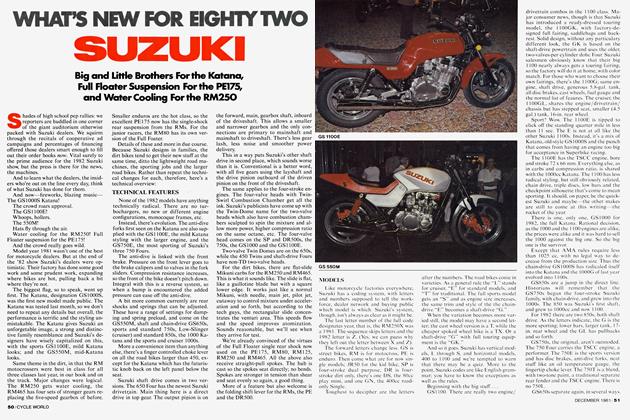

FeaturesWhat's New For Eighty Two Suzuki

December 1981 -

Departments

DepartmentsBook Reviews

December 1981 By Henry N. Manney III -

Features

FeaturesA Guide To Orphan's Homes

December 1981 By Dee Winegardner