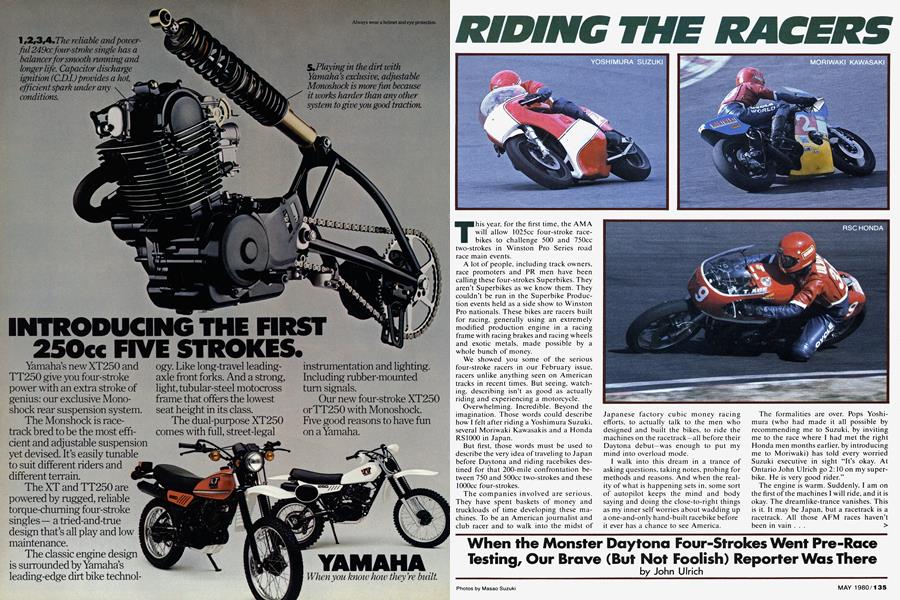

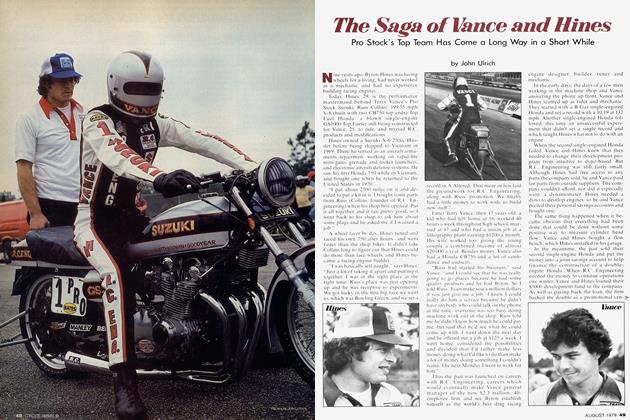

RIDING THE RACERS

When the Monster Daytona Four-Strokes Went Pre-Race Testinq, Our Brave (But Not Foolish) Reporter Was There

John Ulrich

This year, for the first time, the AMA will allow 1025cc four-stroke racebikes to challenge 500 and 750cc two-strokes in Winston Pro Series road race main events.

A lot of people, including track owners, race promoters and PR men have been calling these four-strokes Superbikes. They aren’t Superbikes as we know them. They couldn’t be run in the Superbike Production events held as a side show to Winston Pro nationals. These bikes are racers built for racing, generally using an extremely modified production engine in a racing frame with racing brakes and racing wheels and exotic metals, made possible by a whole bunch of money.

We showed you some of the serious four-stroke racers in our February issue, racers unlike anything seen on American tracks in recent times. But seeing, watching, describing isn’t as good as actually riding and experiencing a motorcycle.

Overwhelming. Incredible. Beyond the imagination. Those words could describe how I felt after riding a Yoshimura Suzuki, several Moriwaki Kawasakis and a Honda RS1000 in Japan.

But first, those words must be used to describe the very idea of traveling to Japan before Daytona and riding racebikes destined for that 200-mile confrontation between 750 and 500cc two-strokes and these lOOOcc four-strokes.

The companies involved are serious. They have spent baskets of money and truckloads of time developing these machines. To be an American journalist and club racer and to walk into the midst of

Japanese factory cubic money racing efforts, to actually talk to the men who designed and built the bikes, to ride the machines on the racetrack—all before their Daytona debut—was enough to put my mind into overload mode.

I walk into this dream in a trance of asking questions, taking notes, probing for methods and reasons. And when the reality of what is happening sets in, some sort of autopilot keeps the mind and body saying and doing the close-to-right things as my inner self worries about wadding up a one-and-only hand-built racebike before it ever has a chance to see America.

The formalities are over. Pops Yoshimura (who had made it all possible by recommending me to Suzuki, by inviting me to the race where I had met the right Honda men months earlier, by introducing me to Moriwaki) has told every worried Suzuki executive in sight “It’s okay. At Ontario John Ulrich go 2:10 on my superbike. He is very good rider.”

The engine is warm. Suddenly, I am on the first of the machines I will ride, and it is okay. The dreamlike-trance vanishes. This is it. It may be Japan, but a racetrack is a racetrack. All those AFM races haven’t been in vain ... >

As Beautiful Yet Tacky As Only A Yoshimura Race Bike Can Be.

The Hamamatsu, track is Suzuki’s a twisty, test 4-mile facility serpent near named Ryuyo. The bike, built by Pops Yoshimura with help from the Suzuki factory, snarls like a superbike from underneath the clothes of an RG.

The engine is standard Yoshimura on the inside, based on the GS1000, displacing 1023cc with a modified eight-valve GS1000 head. But the roller bearing crankshaft is new, with full-circle counterweights instead of the pork-chop-shape counterweights found on the standard GS1000 Suzuki. The bearing cages are of a different design than stock, and while still made of sheet metal, have a new heat treating for more strength and are plated with silver to reduce friction. The fullcircle-counterweight crankshaft provides better engine balance than the standard design crank, damping torsional vibration and avoiding harmonics which could cause the crankshaft to break. In combination with the improved bearing cages, the new crankshaft allows the Suzuki engine to run safely to 11,500 rpm instead of the 10,500 redline previously used by the Yoshimuras. (Yoshimura plans to sell racing crankshafts like this one later in the year, but the one in this bike is the prototype, built of parts carved out of billet by a team of machinists).

Working with Suzuki Motor Co. frame designer Manabu Suzuki (no relationship to the founder of the company), Pops and crew have gone through five different frames since the 1979 Suzuka Eight Hours Endurance Race. The bike’s frame is a little shorter than the Suzuka race bike, giving the latest version a wheelbase of about 55 in. (a stock GS1000 has a wheelbase of 58.7 in.) Head angle is 26°, trail 4.3 in. Frame configuration is similar to that of the RG500 and RG650 Grand Prix machines, but all new geometry must be used to accommodate the taller, heavier, fourstroke engine.

The aluminum gas tank looks similar to an RG tank, but because the frame top tubes are so much higher (due to the taller engine) in relationship to the ground, the tank must be thinner to avoid hitting the rider’s chest and getting in the way when the rider is tucked in.

continued on page 142

continued from page 136

Engine mounts are aluminum. Several sets of mounts allow mechanics to move the engine position in the frame. In practice, Yoshimura mechanics set up the bike with a weight distribution of 52 percent on the front and 48 percent on the rear for Wes Cooley, then found that Graeme Crosby liked the handling better with the engine location and weight distribution changed.

The frame is made of chrome-moly steel and weighs 31 lb., but weight-saving materials are the rule everywhere else. Magnesium is used for the engine cam cover, clutch cover, countershaft cover, alternator cover and ignition cover. All fasteners are drilled titanium, and the RG-style fairing, aerodynamic front fender and seat are made of lightweight carbon fiber. Parts made of carbon fiber can be thinner and lighter than similar parts made of fiberglass, while being just as strong.

All together, Pops says that the bike weighs 348 lb. ready to race.

The swing arm is rectangular cross-section aluminum, with an extensive squarecross-section subframe. (Testing showed that the bike wobbled without the subframe bracing.) The swing arm pivots on standard GS1000 needle roller bearings, and side thrust is adjusted with shims. Chain adjustment is taken care of by blocks in the ends of the individual arms.

Suspension is Kayaba, built especially for this motorcycle. The nitrogen-charged, remote-reservoir shocks are 13.6 in. long. The air-assisted forks have 40mm stanchion tubes (compared to 37mm on the stock GS1000 and Yoshimura Superbike Production machines) and are shorter than standard GS1000 forks. Triple clamps are machined out of solid aluminum. Rear wheel travel is 5.7 in., front wheel travel 5.1 in.

Those travel measurements sound backwards because most bikes have more travel in front, but they are part of a concerted effort by the Suzuki factory to control dive under braking. The Suzuki is fitted with an anti-dive system that works when a plunger activated by applying the brakes blocks off a compression damping passageway routed through a fitting on the outside of each fork slider. That slows down fork compression and avoids the rapid dive normally associated with very hard braking. Rebound damping is urnaffected by the system.

Making the system work required new, larger front brake calipers, calipers delivering so much braking power that the pressure lost in activating the anti-dive system isn’t significant. (Even without the antidive system, the bike needed calipers bigger than those used on an RG, simply because it weighs more than an RG.) >

In changing the amount of fork dive, the anti-dive system limits weight transfer from the back to the front and helps keep the rear wheel on the ground. When the rear wheel stays on the pavement instead of hopping into the air under braking, maintaining control is easier, allowing the rider to brake deeper and harder. In theory, it also makes the bike easier to turn, since a motorcycle handles better as a twowheeler than it does as a unicycle riding on the front wheel only.

Unsprung weight is kept to a minimum and the rear brake is full-floating, again to improve control of the rear end while on the brakes. The Y-shaped rear caliper mount rides on needle bearings and holds the caliper above the axle. The tail of the hand-shaped-and-polished work of art extends below the axle, where it is attached to an S-shaped brake stay leading to a frame mount above the swing arm. The stay is made of several shaped, concave pieces of sheet aluminum welded together with a hollow center. The workmanship is beautiful.

A standard RG rear caliper and radially-drilled disc is used in the rear. Slots in the rear disc—as in the front discs—remove glaze built upon the pads from repeated heavy braking.

Wheels, front and rear, are Dimag magnesium. The rear sprocket is shock mounted to prevent hub damage.

The bike is beautiful, yet tacky, as only a Yoshimura racer—dedicated to function alone—can be.

But, in racing, only function counts.

Just like Graeme Crosby told me, the seating position is very low. The controls are drilled for lightness. Yoshimura mechanics try one shift lever after another from a large assortment, trying to find one to fit my foot perfectly. As they do, I grab the bars and look around inside the fairing nose. The tach is redlined at 10,500. To clear the fairing and avoid crash damage, the front brake fluid reservoir is hoseclamped to the left upper fork tube, with a remote line leading to the master cylinder on the right clip-on.

Controls adjusted. Because rearsets are used with the shift lever reversed on its shaft, the shift pattern is up for low, down for go. (One up, four down.) A mechanic pushes. I stand on the pegs, sit down hard on the seat and let out the clutch. The engine fires, I pull in the clutch, slipping to get underway. With the clutch finally out again and the engine running at about 5000 rpm in first, I grab a handful of throttle and instantly see only sky through the bubble—wheelie. Second. Third. Fourth. Into the first turn, a fast right hand sweeper.

First tight turn, a decreasing right hander with a deceptive entrance. On the brakes, the bike feels funny, alien. Hard to move around on. Seat seems too wide, making it difficult to slide around and hang off. Mental note: Could be trouble.

Then, a left leading onto straight, a series of very fast esses followed by slower esses, followed by a hairpin and a long, long blast down an endless straightaway.

I can’t believe it. This thing is light. Even with clip-ons, the amount of effort needed to change direction is nothing. >

Superbikes are at least twice as hard to ride as this racing motorcycle. A streetbike-made-racer fights the intent of the rider at speed. This real racebike doesn’t.

Powerband: Wide as ever. Don’t want to worry about slipping and sliding exiting a turn? Shift up once, torque your way out. Gas consumption goes down, tires last longer and lap times stay about the same.

But the feeling in the esses is what is worth it all. So light. What line do you want? Take it.

On the straight, fifth gear, 10,200 rpm. Later, Pops will tell me that 10,200 rpm equals 175 mph. Behind the fairing, everything is calm, the wind isn’t trying to tear my head off, and heat from the engine flows up the inside of the fairing at the end of the straight, taking the chill off the crisp ocean air of Ryuyo.

Brakes. Nothing I ever rode before had any. Obviously. This thing stops RIGHT NOW. Little pressure, lots of action. But it still feels strange. The anti-dive works. Instead of the front end slamming down at the turn entrance, the whole bike just settles. I think it makes the bike harder to turn, understeering, then I realize that the different, strange feeling of hauling down from 150 or so into this decreasing radius, first-gear corner without fork dive has my senses confused. If somebody was used to it, and adapted well, this anti-dive could make a really big difference. A positive difference. Maybe a race-winning difference.

The sweeper. Brakes. Right-hander. Too deep. Too late. Radius change. Track edge. Panic. Set the bike upright. Still on brakes. Off track. Grass. Mud. Tires. Wall. Not enough runoff. Turn or hit tires and wall. Can’t.

Pops will kill me.

I’m down.

Curses. Screams. Visions of a telex sent back to the magazine offices: “Arrived Japan, crashed the only Suzuki four-stroke racebike in existence. Will proceed to sabotage other teams as well. Ulrich.”

The bike had finally tipped over at about 5 mph, the only perceptible damage being a broken fairing bubble and a flattened exhaust pipe. Pops isn’t furious, but rather relieved that I wasn’t hurt. The embarrassment of crashing this bike at this place in front of these people is something no man should have to experience.

“Your bike doesn’t handle very well in mud with those slicks,” I tell Pops. “You need knobbies.”

He laughs.

Seeing my nervousness, an important man from Suzuki tells me not to worry. “No one here will tell anyone that you crashed,” he says.

But in the strange way of the racing grapevine, by the time I return home people will have already started calling to see how I survived my rumored 150 mph throw-away of Suzuki’s Daytona bike. >

One Difference Is,When A Rider Says The Bike Is Doing This Or That, Moriwaki Puts On His Leathers And Tries It Himself.

Suzuka City is 125 miles south of Hamamatsu. It’s a new day, a new place, and another bike.

Mamoru Moriwaki says he likes the Kawasaki engine because it is so strong that it can be modified to produce a lot of power without needing special crankshafts and clutch hubs and connecting rods. It isn’t as expensive to modify as a Suzuki or Honda engine, and in the case of Moriwaki, that’s an important consideration.

While Moriwaki has limited ties to the Kawasaki factory, he is in essence a privateer. His racing parts and service business is thriving in spite of the fact that Moriwaki and his father-in-law, Pops Yoshimura, recently ended their association as business partners. (Moriwaki designed and manufactured some of the Kawasaki parts formerly sold by Yoshimura as Yoshimura parts). The achievements of New Zealander Graeme Crosby in European F-l events brought the spotlight to Moriwaki, and his bikes are very competitive.

Like the Yoshimuras, Moriwaki has been continually developing his machine since the 1979 Suzuka Eight-Hours race. One difference is that when a rider tells Moriwaki that the bike is doing this or that, Moriwaki puts on his leathers and tries the motorcycle himself. He hasn’t set any lap records recently, but did hold a class lap record at one Japanese track in the early 1970s and definitely still knows his way around the pavement well enough to tell what a racebike is doing, where it is doing it, and ultimately, why it is doing it. Because of Moriwaki’s direct link from riding to building, his latest Kawasaki (which he refers to as his “monster”) has evolved more quickly than the Yoshimura Suzuki. Moriwaki has reached about the same point as the Yoshimuras have in handling, but in two frame design steps instead of six.

Moriwaki’s bike is straightforward and conventional. For example, Moriwaki believes that Suzuki’s use of the anti-dive system is made necessary because the rear suspension of the Suzuki has too much travel and too little weight on it, causing the rear end to rise too much, too quickly when braking for a turn. Excessive weight transfer impairs handling since a motorcycle cannot turn on one wheel (the front wheel). Anti-dive can cure that, but since in effect the steering head angle does not change during pre-turn braking with the anti-dive system, putting the bike into the turn can be more difficult, Moriwaki says, continued on page 152 continued from page 149 and riding the motorcycle may require a different technique—braking, then turning, versus braking to the apex.

The Suzuki anti-dive system may work eventually, and may work well, Moriwaki thinks. But he is also quick to point out that it is very difficult for engineers to translate rider input into system design.

Moriwaki builds his own frames out of hand-bent chrome-moly steel, in jigs he built himself. His Suzuka bike set a new lap record for production (engine) based machines. But that bike was built with a long wheelbase to suit rider Crosby’s stuffand-slide style of riding, where stability gained while drifting the rear end is more important than a longer wheelbase slowing down steering.

Crosby has since joined the Suzuki factory race team, and Moriwaki built his latest chassis to have perfectly neutral steering. Wheelbase of this new machine is 57.1 in., versus the older bike’s 59.1 in. Head angle is 28°, trail 3.9 in.

Moriwaki’s frame weighs 26.5 lb. compared to a Stocker’s 39.7 lb. The steel rectangular-cross-section swing arm weighs 8.4 lb. compared to stock’s 8.8 lb., and rides on tapered roller bearings.

Rayaba forks with internal modifications and air caps are fitted, while rear shocks are racing Rayabas identical to those used on Yoshimura Superbikes. Triple clamps are off a TZ750 Yamaha. Wheels are both 18-in. Dimag magnesium, the rear with sprocket shock mounts. Brakes are Lockheed calipers and thinned RZ1000 discs in front and a thinned and drilled RZ1000 disc in the rear. The rear disc is grooved on its edge to increase heat dissipation. The rear master cylinder uses a remote reservoir to reduce fluid boiling, moving the fluid away from engine heat.

Moriwaki positions the front brake calipers ahead of the forks because he says that locating the calipers behind the forks can contribute to slow steering. And he prefers an 18-in. front wheel to avoid the understeer influence of a 19-in. front wheel. (A bike with a smaller front wheel will turn faster, all other things being equal.)

Engine mounts are aluminum, with a mixture of titanium and steel bolts used throughout. (“Light weight is money,” says Moriwaki in a bit of irony. At his side is a carbon fiber fairing for his monster. He explains that before Daytona, titanium bolts will replace all the steel bolts used on his bike.)

Moriwaki’s basic engine modifications Were covered in the February issue. But since we last saw his bike, displacement has increased to 1024.119cc, (just under the 1025cc AMA limit for four-strokes)> and the valve shim system has been changed. Moriwaki now uses tiny caps fitting over the cut-down ends of the valve stems. The caps are smaller and lighter than the usual underbucket racing shims.

Ignition is still total-loss, batterypowered electronic. Moriwaki would like to use a self-generating magneto CDI system, but has been unable to find one meeting his requirements.

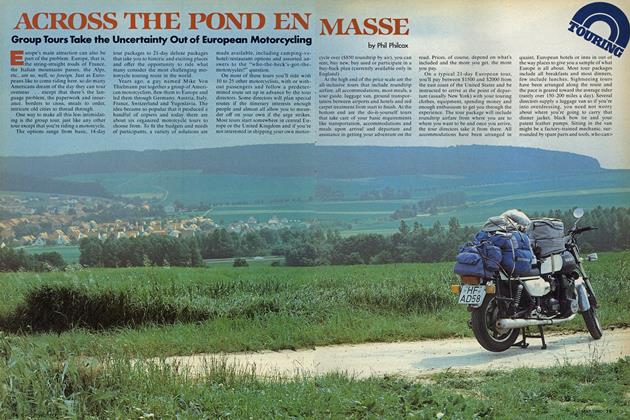

Suzuka Circuit is the longest 3.7 miles in the world, 13 or 14 corners depending upon how you count, uphill, downhill, with fast turns, slow turns, decreasingradius sections of turns—and bumps.

The Yoshimura/Suzuki team found last year that bikes that work at Suzuki’s essentially-flat Ryuyo course don’t necessarily handle well at Suzuka. But according to Moriwaki, what works at Suzuka will work anywhere.

It’s here that Moriwaki tests and rides, experimenting with fork offsets, head angles, wheelbases, suspension, making changes one by one, always looking for improvements.

I started out on the course riding one of Moriwaki’s Superbike Production machines, a bike he’ll enter in the Daytona Superbike race. The front straight ends in a right-hand, tightening sweeper, heads through uphill esSes, turns left into a short chute, right uphill through “Pridmore corner” (where Reg Pridmore crashed a Honda in 1978 and Moriwaki’s Kawasaki in 1979, both times in practice for the Eight-Hour), straight, jog right, hairpin left, sweeping downhill-uphill rights, over a crest, two hooks left, straight, fast left, wide-open-in-fourth (or fifth if you’re Crosby) right and then the straight.

It’s a hard track to learn and harder to ride quickly.

After pitting, climbing on Moriwaki’s monster and finishing half a lap, the difference between an AMA Superbike and a four-stroke GP machine stands out like the rising sun. By comparison, the superbike, as good as any Kawasaki I’ve ridden, is wobbly, loose, disjointed, and unpredictable. Riding a four-stroke built for racing with a proper racing frame is much easier. Going fast stops being the battle a Superbike can make it.

Moriwaki’s bike feels light, especially in front, the bars instantaneously clicking against the steering locks right-left-right— then steadying just as suddenly—as I hit a bump exiting the final, frighteningly-fast curve, on the gas.

It stops. Hard. It turns, just as much as I want, when I want. Moriwaki has achieved his aim of neutral steering.

Still, the bike doesn’t feel feather-light like Yoshimura’s machine, and Moriwaki says his racer weighs 397 lb. with gas and oil.

continued on page 158

continued from page 154

Going by the figures provided by Pops Yoshimura and Moriwaki, the Moriwaki Kawasaki weighs almost 50 lb. more than the Yoshimura Suzuki. Since we haven’t weighed both bikes we don’t know exactly how much the machines weigh. But Moriwaki’s Kawasaki doesn’t feel 50 lb. heavier, and is easier to ride. It feels natural, goes where I want, and is well-suited to hanging off—I have no trouble moving around on the seat. I can brake and change directions at the same time, braking to the apex. The bike doesn’t click the bars once I learn the smooth line through the turns, but the front end still gets light on some parts of the course.

Moriwaki’s engine isn’t as violent as the Yoshimura Suzuki, and the bike doesn’t seem as fast. But that may be a function of: 1) the Kawasaki’s flat torque curve and excellent powerband: 2) Suzuka’s shorter straight and; 3) my own getting re-accustomed to very high speeds after a year of riding nothing faster than 145 mph. At Suzuka, Moriwaki’s Kawasaki tops out at 9500 rpm on the back straightaway, about 162 mph.

The bike feels like an old friend, but the course still holds surprises. I’ve taken 15 seconds off my lap times in 30 minutes of riding.

Returning the next day for another brief practice session (this time on the short course, formed by using a cutout), I learn the course and bike well enough to comfortably drift in several corners. Now, with the suspension being worked at speed, the front tire chatters.

Moriwaki nods when I come in. There is no time to experiment with different tires or fine-tune the suspension to suit my riding style.

Still, I am convinced that Moriwaki’s bike can compete with the Yoshimura Suzuki on this type of course. At Daytona it will be harder. I don’t think that Moriwaki’s bike makes as much power as Yoshimura’s. Moriwaki’s bike weighs more (he doesn’t have the kind of massive factory support that allows Pops to use magnesium engine covers and exotic metals and constructions) but handles and stops well.

Daytona is a long race. The lightest, fastest bike won’t necessarily win.

Moriwaki hands me a paper with my lap times written on it.

Three days ago, after crashing the factory Suzuki, I could have died a thousand deaths.

Today, staring at the list of lap times, I am elated. >

When Honda Says The Daytona Bike Will Have the Same Engine And A New Frame, What They Mean Is, It Will Be A Four-Stroke Painted Red.

Honda. The team with the most money. Hondas have ruled European endurance racing for years, but mighty Honda is capable of being beaten. At Suzuka Circuit in 1978, Pops Yoshimura put Wes Cooley and Mike Baldwin on an American-style superbike and won the annual endurance race.

Honda owns Suzuka Circuit and sponsors the endurance event each year. Honda’s Racing Service Center Corp. (better known as RSC) is located in the track infield. The loss on the home track in 1978 was embarrassing, but it was an embarrassment not repeated in 1979. Hondas dominated last year, and the fastest of the Hondas entered—the RS1000 which qualified third and led for several hours until breaking—now stood before me.

In all fairness, the Hondas which show up at Daytona with riders Ron Pierce and Freddie Spencer won’t be exactly like this one. This is an endurance bike. But according to Mr. Satoshi Ichihana, head man at RSC’s Suzuka office, the Daytona bikes will be basically the same engine package in a lighter, sprint-race-only chassis.

Honda plays close to the vest. Pops Yoshimura has known me for a long time, has let me ride several of his bikes, and at least until this trip, has never regretted it. Moriwaki is unknown in America and has nothing to lose and lots to gain by telling me about his bikes, and has Pops’ recommendation on top of that.

But while Mr. Ichihana is very friendly and cooperative, the simple fact that I am even at RSC is something of a wonder. Honda is so huge it really has nothing to gain.

I had met Mr. Ichihana at the 1979 Suzuka Eight-Hours race, but I think the real reason I will be allowed to ride an RSC machine is the recommendation of Moriwaki. On the track, Moriwaki’s machines compete with RSC’s racebikes. But off the track, the rivals have a respectful, friendly relationship. Moriwaki’s factory is only a few miles from Suzuka Circuit. Honda RSC riders have been known to ride on Moriwaki’s bikes, just to see how they handle. They’ve also been known to ask Moriwaki’s opinion of certain aspects of frame design and suspension setting. And, on occasion, Hondas built by RSC have headed onto the racetrack with certain Moriwaki-built engine components inside.

This isn’t the latest RS1000. It’s a good one, as its Suzuka endurance race performance showed. But it isn’t a Daytona bike. When Mr. Ichihana says that a Daytona bike would have basically the same engine in a new frame, I get the feeling that what he means is, it will be a four-stroke painted the same colors.

Information on the engines isn’t a problem: it’s all in a manuafipublished by RSC, since RSC sells engine kits. (The manual is available from RSC through Honda dealers).

But the chassis is another matter.

Mr. Ichihana tells me that the frame is a modified CB900 frame.

Yes, it certainly is modified. As in cutting it up and sending the chunks of metal to the foundry where tubing for new frames is manufactured.

Honda RSC actually sells the parts for two lOOOcc plain-bearing-crankshaft racing engines, the RS1000 (based on the CB900) and the RCB1000, (based on the CB750).

The RS1000 has a bore and stroke of 67.8 x 69mm for a displacement of 996cc, and makes a claimed 125 bhp. The RCB1000 has a bore and stroke of 70 x 64.8mm for 997cc and a claimed 125 bhp.

Parts included in the RS1000 engine kit include crankcases, cylinders, cylinder head, dry clutch, transmission, CV carburetors, ignition, pistons, rings, connecting rods, ignition and alternator covers, cams, valves, valve springs, valve spring retainers, valve spring buckets, cam chains, primary chain, exhaust system, tach and dry sump lubrication system. An extensive package. >

Compression ratio with the kit is 11:1. Cam timing opens the intake valves at 35° BTDC and closes them at 40° ABDC; while the exhaust valves open at 50° BBDC and close at 25° ATDC.

The entire chassis is special and not very much related to the CB900. Suspension is Showa (nitrogen-charged shocks in the rear), including quick-release pivoting front axle clamps. Triple clamps are carved out of aluminum. Wheels are racing CornStars, 2.5 in. wide in front, 3.5 in. wide in the rear. Brake calipers are Nissan.

Ready to race, Honda claims that the RS1000 in this trim weighs 419 jb.

After an RSC test rider cuts a few laps of the short course to make sure the tires are warm and the engine running well, it’s my turn.

The Honda feels incredibly light, lighter than the other bikes I’ve ridden on this trip to Japan. That’s in spite of having the highest claimed weight.

But while it feels lighter, and even though it seems like the RS1000 Honda can go anywhere on the track at will, it also is harder for me to move around on the seat and hang off when riding the Honda, compared to Moriwaki’s Kawasaki.

The amount of effort needed to turn this bike isn’t much. I brake into a turn, entering at the same speed, on the same line, hanging off just as much as I did the day before on Moriwaki’s bike. Yet on the Honda I find myself hooking into the inside of the turn. The bike gives me more steering action than I expect from my input, as if to say, go faster in this turn.

The Honda steers quickly even though it has the longest wheelbase, 59 in. It does have a steep head angle, 26°, which is steeper than the Moriwaki Kawasaki’s 29° but no steeper than the Yoshimura Suzuki’s 26°. The answer could lie in triple clamp offset and trail, but while I know that the Yoshimura bike has 4.3 in. of trail and the Moriwaki machine has 3.9 in., Honda isn’t telling how much trail the RS1000 has.

More than Moriwaki’s bike, this Honda demands being ridden at racing speeds to feel normal. Moriwaki’s bike felt the same at both slow and fast speeds. This Honda must be ridden relatively hard to work.

But any advantage the Honda may have in light steering is lost in terms of power. This Honda is definitely the slowest of the three bikes, reaching 157 mph at 9500 rpm, and accelerating more slowly than the others. On the other hand, the 32mm Keihin CV racing carbs keep the engine running smoothly even when the tach needle drops to its stop as the engine rpm falls below 4000. I found that out when I blew the entrance to the course cutout U-turn, continued on page 166

continued from page 162 yet when I exited the turn and grabbed the throttle, the bike ran right up onto the powerband and away without burbling. The best power started about 7000 rpm and ran to 9500, where I shifted. (I had forgotten to ask what the redline was, so picked 9500 as being safe. Later I would be told that the rpm limit is 9000.)

The amazing no-bog CV carburetors may hurt the bike’s top end power, but their response from low revs, light returnspring tension and good fuel economy are all advantages in long races. Hondas seen at Daytona will probably use 31mm Keihin CR slide-throttle carbs for maximum power.

Brakes are good, but controlling the rear is more difficult than on the Yoshimura and Moriwaki machines because the Honda doesn’t have a floating brake.

Before I was up to full speed or ready to pit, my foot started slipping off the shift lever, causing me to miss several downshifts.

A pit stop revealed that the oil fittings ahead of the left footpeg were leaking, and that the footpeg and shift lever had been oiled. By the time mechanics stopped the leak and I finished making notes, practice time was up, too soon to suit me.

Honda: Not enough power. Too heavy. Light handling.

Nothing the factory can’t cure before Daytona. The men from RSC wouldn’t say, but already I had heard the rumors from inside American Honda: frames complete with swing arms that weigh less than conventional swing arms alone; engines with new heads, new valve angle, new bore and stroke, titanium connecting rods, new carbs, new 4-into-l exhausts replacing the 4-into-2-into-l systems used on the RS1000; new 39mm o.d. fork tubes with stronger sliders to match; supersize “Ron Pierce brakes,” giant discs with oversize calipers to withstand Pierce’s hardbraking Bakersfield line; shocks built by Showa to match the action of the racing Kayabas used on Yoshimura Suzukis; magnesium racing wheels; wind-tunnel carbon-fiber fairings; ounces of titanium, magnesium, aluminum replacing pounds of steel.

Most of all, truckloads of money making anything possible.

This is written before Daytona. But by the time you see it in print, Daytona will be over. We’ll know then which of the three teams—Yoshimura, Moriwaki, or Honda^ has the fastest four-stroke,#nd which o.ie has the best finish.

Whatever the outcome, the four-strokes will add a new dimension to the Daytona 200 and other Winston Pro races, with the race fan becoming the biggest winner. S