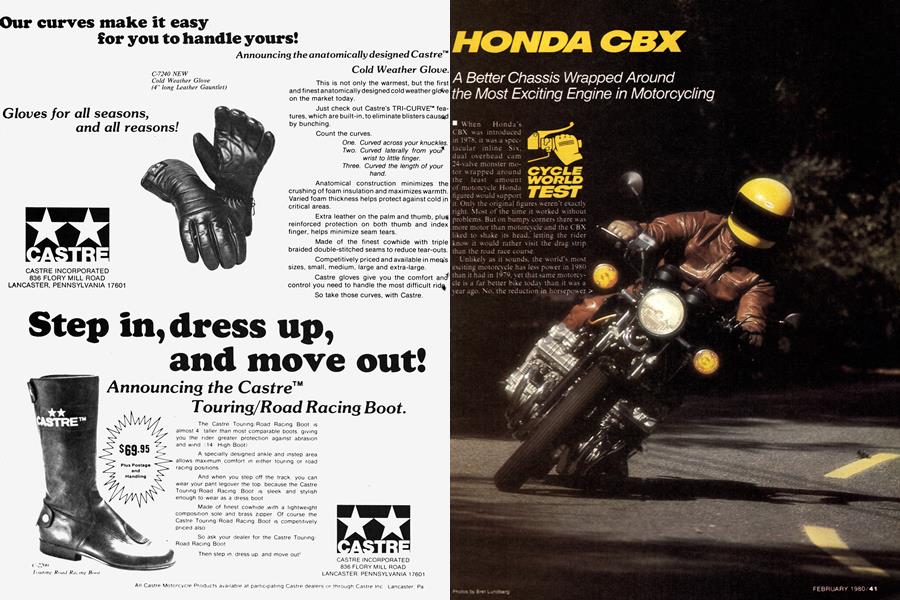

HONDA CBX

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A Better Chassis Wrapped Around the Most Exciting Engine in Motorcycling

When Honda's CBX was introduced in 1978, it was a spectacular inline Six, dual overhead cam 24-value monster motor wrapped around the least amount of motorcycle Honda figured would support it. Only the original figures weren't exactly right. Most of the time it worked without problems. But on bumpy corners there was more motor than motorcycle and the CBX liked to shake its head,letting the rider know it would rather visit the drag strip than the road race course.

Ln~1\ t ir~is. th~ \kc~r!L m~st nt~'r~e ha~ s r~'~er n h~n had in 1~'-. `.et that same Imi~torc\ a far heiter thdn v~a~ sear . \c~. th~ redu~ti~n in hL~r~ .~r >

isn’t what improved Honda’s 1980 CBX, but neither has it hurt the CBX significantly. The chassis updates, however, more than make up for any slight drop in forward thrust.

Honda claims this year's CBX is a better handling motorcycle than last year's CBX because of the new adjustable damping shocks and the new V-rated tubeless tires. But there’s more to it than that. Besides the higher rated tires and the dampers that Honda’s also fitting to the new CB750. the swing arm is now made of thicker steel and the swing arm pivot has been changed

from a plastic bushing on each end of the swing arm bolt to a combination of double ball bearings and a needle bearing. The angular ball bearings hold the swing arm in place against side thrust and the needle bearing, located on the drive side, takes the loading from the chain. The new pivot is an enormous collection of hardware.

So much for swing arm flex. Up front the tapered roller steering head bearings have been moved 2mm farther apart for greater rigidity and the forks have been completely redone. There are air caps to pressurize the legs for a higher spring rate. New bushings at the top of the sliders are made of a combination Teflon, lead and bronze, which Honda claims is better than Teflon for bushings. Sliders are 1mm larger for 1980, 45mm compared to 44mm used last year. Stanchion tubes, how ever, remain 35mm diameter. Variable rate fork springs have rates ranging from 34.6 lb./in. to 40.4 lb./in. to 51.9 lb./in. compared to a dual rate spring with rates of 46.1 and 57.6 lb./ in. used last year. Fork travel remains 6.3 in. Rear wheel travel is 3.9 in. The air pressure in the forks, 10 psi plus or minus 3 psi, is hardly enough to make a difference in the total spring rate, but what-the-hell, the other bikes have it.

The new rear dampers have been used on the European CBXs since the beginning. A small lever at the bottom of the shock adjusts compression damping to either of two settings, while a collar at the top of the shocks sets rebound damping to any of three settings. Spring preload also is adjustable, with five positions.

In addition to the different damping rates, there are blow-off springs covering additional holes in both the rebound and compression damping mechanisms so especially harsh shocks are absorbed by lighter-than-normal damping rates.

Tire size is the same, a 3.50-19 in front and a 4.25-18 in back, but the rear rim is wider this year. 2.50 rather than the 2.15 used last year. Also the rims are reversed aluminum ComStar wheels painted black and with polished edges. Last year the CBX had polished aluminum wheels, not reversed. The tubeless tires are now V-

rated, indicating they are capable of w ithstanding sustained speeds over 130 mph.

Brakes on the CBX are unchanged—sort of. The calipers and pads and discs are the same size and made of the same material, but the machining process used to grind the discs is different now to eliminate an uneven surface that caused a pulsing through the brake lever.

All of the chassis changes on the 1980 CBX are obvious improvements that make the CBX a better handling motorcycle. Engine modifications on the 1980 model are another matter. Beginning in 1978 motorcycles had to meet emission standards set by the Environmental Protection Agency. For large displacement motorcycles the standards became more stringent in 1979 and again in 1980. There are no further changes in the smog laws planned, however. To meet the tougher standards most motorcycle manufacturers have leaned out carburetion and some^ have changed equipment.

Honda has one other concern about the CBX. At least one European country now has a prohibition on motorcycles with more than 100 horsepower, others have discussed such a ban and our own highway safety boss Joan Claybrook has attacked the Japanese motorcycle manufacturers for producing such powerful motorcycles as the CBX. Honda's response has been to detune the CBX so it produces less horsepower in addition to putting out lower emissions.

To cut emissions, the carbs, all six of the 28mm Keihins. have only the low speed jet

and a secondary main jet this year, the

primary main jet is gone. Also, the needle has only one slot so it can’t easily be raised (though a washer under the clip might do the trick).

Horsepower has been cut through the use of different cams with less lift and less overlap. The exhaust cam timing has been moved up 5° for less overlap, while exhaust cam lift has gone from 7.5mm to 7.0mm. Intake cam timing is the same, but lift has dropped a half millimeter to

7.8mm. The results of the cam change is a reduction of peak power by about 3 percent, according to Honda, so the horsepower would go from 103 bhp to no more than 100 bhp. A side benefit should be an increase in mid-range power, which Honda says has increased about 7 I percent in the range from 4200 to 6200 rpm.

Internal baffling of the mufflers has been revised for less restriction and thus more power, though the sound level is still not much higher than that of an electric drill—but more exciting.

Finally, the mechanical ignition advancer of the CBX has been modified to advance ignition timing faster and farther than on last year’s CBX. The very first 1980 CBXs didn’t have the heavier centrifugal advance weights when they came from the

factory, and early tests of the CBX indicated a more severe power shortage than Honda planned, so the engineers went back to the drawing boards and soldered some lead on one of the sets of weights in the advancer unit. The CBX uses a twostage mechanical advance unit with two sets of weights, a light set and a heavy set, so the heavy set provides 23.5° of advance at 2500 rpm and the light set increases the

advance to 34° at top speed.

Transmitting the reduced power to the rear wheel is a smaller 530 chain. Honda says the 530 chain will last longer than the previously used 630 chain because it’s made from better materials, even though it’s more expensive than the larger chain. % Other benefits are lighter weight

\and less noise. It’s still an O-ring. chain, sensitive to

some lubricants, but rewarding careful lubrication with long life.

An oil cooler that’s 20 percent larger for 1980 helps cool the 5.7 quarts of oil used in the engine and transmission. For casual use the previous oil cooler was more than adequate, but for competition the larger oil cooler offers additional cooling.

To help an owner keep all this wonderfulness, Honda has thoughtfully provided a cable with which the CBX can be locked

to a tree or a post or whatever solid object is handy. The cable doesn’t have its own lock like the BMW security cable. Instead it fastens to the helmet lock, which has been beefed up to handle the job. The cable is stored in a locking compartment built into the tailpiece behind the seat. While a cable doesn’t make the CBX theftproof, it is better than nothing and it’s nice to see it included w ith the motorcycle.

Of course all the new tricks are only icing on the cake for the super trick CBX. After all, what’s a security cable compared to jackshaft-driven ignition and clutchconnected 350-watt alternator? If it’s trick you want, look at the two-piece camshafts and accelerator pump on the carbs, which are mounted on canted heads so the carbs are tucked in.

All this wizardry would be worth diddley-squat if the motorcycle didn’t perform. Make no mistake about it. Forget that it doesn’t have 100 horsepower. Don’t worry about the emission rules. The CBX Performs. There is still no production machine with any number of w heels that can grab a rider and sling him forward with such excitement as the CBX. This is one motorcycle for which a rider needs a helmet to keep his eyes from being pushed through the back of his head.

When that throttle is cracked those six hyperactive pistons instantly jerk the crankshaft into orbit while the tach needle bounces up to the 9500 rpm redline. There’s as much flywheel effect on the CBX as in a model airplane motor. Release the smooth clutch with the engine spinning and the CBX is ready for the next gear in a heartbeat. The cam changes do provide a tiny bit extra mid-range

power, >

but the real thrills begin when the tach is at 7000 rpm. Kept near the redline the CBX will terrify the mere mortals who ride smaller machines and give the power hungry a highway high like nothing else.

But there’s more to it than that. First the CBX must be warmed up because when it’s cold it won’t run without constant attention to the throttle and choke. And just off idle the CBX refuses to accept throttle if the bike’s in gear. It just stalls unless it’s revving over 3000 rpm when the clutch is engaged. Rideability leaves something to be desired.

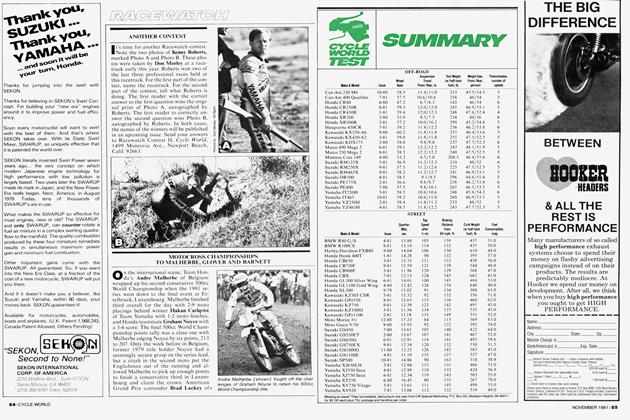

For the record, the quarter mile time for the new CBX was 11.93 sec. at 114.06 mph. Compared to last year’s CBX times of 11.36 sec. at 118.11 mph the performance is a little disappointing. But that’s like saying Albert Einstein could have been smarter. The CBX is, when all’s said and done, still faster than a Kawasaki KZ1000, or Yamaha XS1Í00, or Suzuki GS1000. A 11.93 sec. quarter mile, though, should be good enough for second place behind Suzuki’s new GS1100.

Unlike last year, the 1980 CBX is not limited to bludgeoning quarter miles to death. It’s a better all-around motorcycle. The new suspension pieces have all but eliminated the high speed handling deficiencies. Cranked over hard in a tight corner the CBX glides around, the end of its folding aluminum footpeg slipping along the pavement. Speeding around high speed bumpy sweepers the new CBX goes where it’s pointed without trauma. At really high speeds, where the 85 mph speedometer ran out of numbers 30 mph ago, a bump or dip can make the forged aluminum handlebars oscillate for a few moments until the motorcycle damps out the motion. This, despite its over-600 lb. weight, is a good handling motorcycle. This is not to say the CBX is a good handling motorcycle like a Honda Hawk is a good handling motorcycle. The CBX is still a 600 lb. motorcycle and that takes effort to steer at low speeds and high speeds. What makes the CBX a good handling motorcycle is its stability and predictability. Put a hard crank on the bars and the CBX falls hard into a turn. A gentle pull gives a gentle lean. Nothing is hidden in the ’80 waiting to surprise an unsuspecting rider. And the better quality shocks and strong swing arm pivot should keep the handling under control for some time. Now the small front forks become the weak link.

As awesome as the CBX is, it is amazingly docile when cruising down the highway. The forks are almost soft, able to absorb any normal bump. The seat is hard, but it doesn’t numb the butt as quickly as some other seats do. The ride can be bouncy because of the stiff rear springs and shocks, but that’s a small price to pay for the stability of the new CBX. A low gear ratio means the CBX is buzzing away at 5000 rpm at normal cruising speeds, sending a slight vibration through the bars, but not as far as the mirrors. Though the motorcycle vibrates, the motor doesn’t. Reach down and touch the motor while the Honda is cruising and the motor is dead still, as if it were parked in a garage.

That enchanting howl from the 6-into-2 exhaust system fades away to silence once the bike is in its element. But the best sound the CBX makes is the ripping sound of rubber being torn from the rear tire by a sticky drag strip. It’s music to the the ears, if not to the wallet.

Braking performance is excellent. Lever pressure is light for almost instant stops, while the rear brake can lock up the tire a bit too easily. At speeds where the CBX is breathing hard—there is such a thing for the stout hearted—all of the braking power is being used.

The supporting cast, that motorcycle wrapped around the CBX motor, is generally an excellent piece, but not perfect. The seating position is good, the bars comfortable and pegs in a reasonable position. For those who prefer a more sporting position there’s the European control kit option consisting of shorter bars and control cables. The kit definitely makes the CBX a more sporting proposition, but installation is a day’s job because the motor must be lowered from the motorcycle so the cables can be changed.

Red-numbered gauges aren’t easy for all to read. The mirrors are clear of vibration, even when the handlebars aren’t. As usual, the quartz-halogen headlight has too great a separation in angle from high to low beam so the low beam is too low and high beam is too high. The front signal lights function as running lights to make the motorcycle more visible. Maintenance on the CBX won’t be cheap, and neither will repair. During track testing the CBX fell on its side while nearly at a standstill, yet the crankcase end cover cracked, causing an oil leak that made the machine unrideable. Should street motorcycles be that fragile? No.

Honda purposely under-rates its gas tank capacities but the CBX has the most under-rated gas tank of all.

The factory spec, sheet says the tank holds 5.3 gal. with 1.3 gal. in reserve. We

checked the capacity by draining the tank into a calibrated measuring cylinder and the main petcock gave us 6 gal. exactly. The reserve tap gave us just 0.22 gal. more. That offers barely 10 miles in an optimistic estimate, not enough when gas stations often shut down early at dusk in rural districts.

There is more gas in the tank however, 0.3 gal. to be exact, because the rear end dips below the level of the petcock. But you’d have a job getting it out without

taking off the tank. More significantly, it’s difficult to get the 6 gal. into the tank anyway because the filler has a deep neck that makes filling over 5 gal. a chore without spilling gas.

We wouldn’t labour the point but for the fact that the gas mileage can easily drop below 30mpg, putting a 160 mile limit on the range. Overall the CBX returned 39 mpg.

As a sports bike the CBX can be excused a few inconveniences. And considering the

exotic nature of the engine there are amazingly few sacrifices. The cold blooded nature of the beast is not unusual. Even the styling of the machine is less exaggerated. The engine has been tamed ever so slightly but overall the CBX is a much better machine.

Despite the engine changes, and because of the other new pieces the 1980 CBX is as good as any previous superbike.

HONDA

CBX